MINA, SAUDI ARABIA (AP) – As hundreds of thousands of pilgrims walked in the footsteps of the prophets beneath a sweltering sun, contracted cleaners in lime-green jumpsuits held out matching plastic bags to collect their empty water bottles.

It takes tens of thousands of cleaners, security personnel, medics and others to make the annual haj pilgrimage possible for 1.8 million faithful from around the world. As the haj concludes on Friday, the workers will begin a massive, weeklong cleanup effort.

For the cleaners, who are migrant workers, it’s a much-needed source of income. But this year it was particularly trying, as temperatures regularly hovered around 45 degrees Celsius during the five-day pilgrimage, most of which is held outdoors with little if any shade.

“This job is not easy,” said a 26-year-old trash collector as he took a quick break to splash water on his face before rushing back to his position as another wave of pilgrims approached. “The heat is too much.”

He was among six cleaners, all from Bangladesh, who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity, fearing reprisal. They said they are paid SAR600 (about USD160) a month. They work 12-hour shifts for a few weeks surrounding the haj, with no days off, before returning to other cleaning jobs around the kingdom.

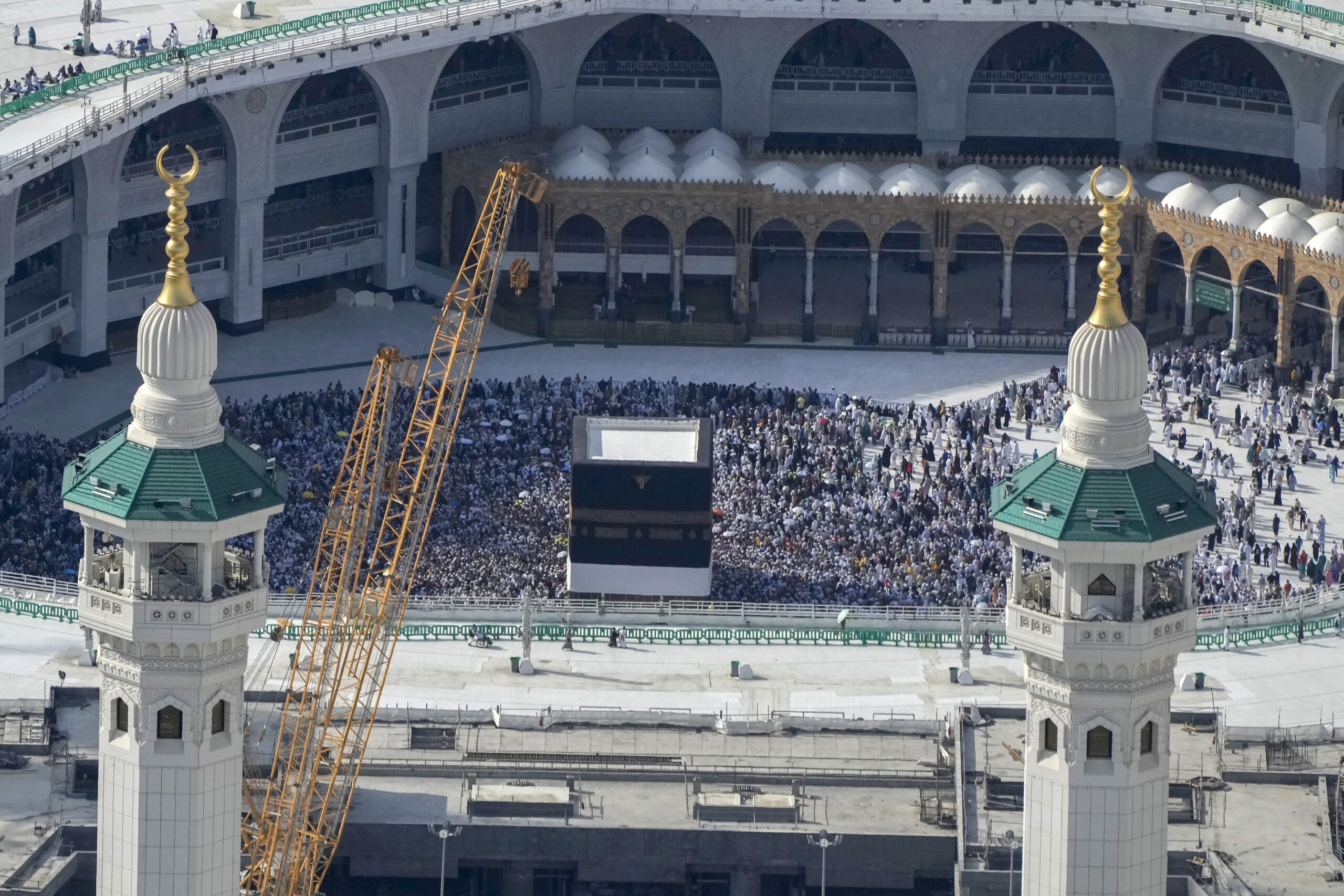

The haj pilgrimage to Makkah is one of the five pillars of Islam, and all Muslims are required to undertake it at least once in their lives if they are able. This was the first time in three years it was held without coronavirus restrictions.

The haj concludes on Friday, as pilgrims circle the cube-shaped Kaabah for a final time and then depart from the holy city. Men often shave their heads after completing the ritual stoning of pillars representing the devil, and women cut a lock of hair as a sign of renewal.

Pilgrims insisted the journey was worth it despite the heat. For many Muslims it is the highlight of their spiritual life, a journey that wipes away sin and brings them closer to Allah the Almighty. Some spend years saving up money and awaiting a permit in order to go.

The haj is also a huge source of pride and legitimacy for the Saudi royal family, which serves as the custodian of the Islam’s holiest sites and invests billions of dollars in organising the annual pilgrimage, one of the largest religious gatherings on earth.

For the cleaners, it is also a job, and this year it was an especially tough one.

The sun beat down on the open spaces and roads, and reflected a blinding light off the white marble of the holy sites. On some days there was hardly a breeze, while on others a hot wind whipped up gusts of sand. Mobile phones overheated and died within minutes.

The Saudi Health Ministry said more than 8,400 pilgrims were treated for heat exhaustion or heat stroke, with nearly half of them hospitalised.

Mehwish Batool, a 29-year-old from Pakistan who was on her first pilgrimage, said she had to use a spray bottle to keep from getting dizzy, and that often the only shade to be found came from the umbrella hat she was wearing.

“There is nothing here, there is only the sun right above us,” she said. “I love the experience, but the worst part is the heat. And there is nothing to protect us.”

Saudi authorities have set up canopies and industrial misters in some places. The pilgrims carried umbrellas and spray bottles, dousing themselves with water and gratefully accepting free drinks handed out along the routes between the holy sites. Then they tossed the bottles into the bags held by workers, or onto the ground to be collected later.

Spokesman for the Makkah municipality Usama Zaytoun said a total of 14,000 workers are contracted from private companies to clean up during and after the haj. He declined to comment on their salaries or working conditions, but said there were no reports of health problems among the workers this year.

He said it takes about a week to clean up after the pilgrimage. Municipal workers collect the waste and feed it into 1,200 industrial compactors before sending it off to be processed. They spray the streets, campsites and bridges in and around Makkah with disinfectants and pesticides, which Zaytoun said are designed to protect the environment and prevent the spread of disease.

Their efforts do not go unnoticed. Sheikh Dawood, a 40-year-old first-time pilgrim from India, was one of several pilgrims who could be seen giving money to the workers in honour of Aidiladha, a charity-focused holiday coinciding with the last three days of the haj. Other pilgrims offered the cleaners water or a refreshing spray from their handheld misters.

“They are doing great job,” Dawood said. “Their service is excellent. We cannot say it with words. So there should be support for them.”

He said they would be even more blessed by Allah the Almighty for working in the heat. “I think everyone is very thankful for them,” he added.