AFP – Perched atop a metal ladder, Athanassia Pistola helps her husband nail the roof of a temporary pen for their farm animals that survived a gigantic fire that ravaged northeastern Greece in August.

Next to it, all that remains of their previous sheepfold is a pile of melted iron and other materials, the rest of it swept away by the flames that also destroyed part of the important Dadia national park, situated near the Greek-Turkish border.

Out of the Pistola family’s nearly 80 goats, only three survived, their backs still charred.

Unprecedented in Greece in its intensity, the Dadia fire has been classed by the European Commission as the largest ever recorded in the European Unioon.

“We did not expect the fire to spread so quickly… it crossed 40 kilometres in eight hours,” said Kostas Pistolas, 63, whose family has grown cattle in the area since the early 20th Century.

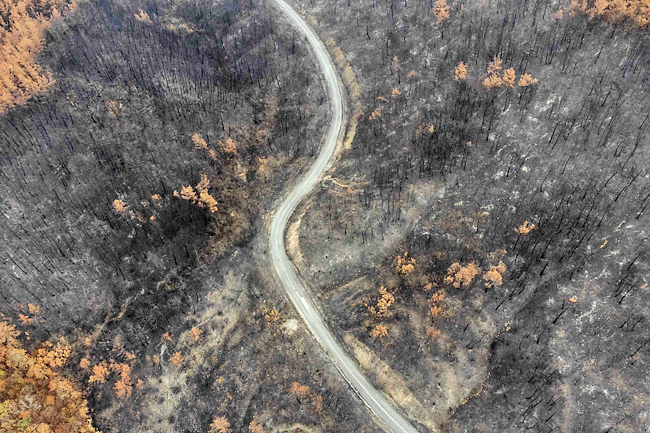

His eyes are fixed on a dozen surviving cows wandering among charred trees in a now-apocalyptic landscape.

Burning for three weeks, the fire consumed more than 90,000 hectares of woods and crops in an area protected by the European Natura network, and renowned for its biodiversity.

In the park itself, the fire killed hundreds of animals including deer, reptiles and turtles, according to head of the Thrace biodiversity protection association Dora Skartsi.

“It was a severe blow to a rich ecosystem,” Skartsi told AFP.

The smell of burning still permeates this area in southwest Evros, where a first fire broke out on August 19 before linking up with another on the heights of Dadia.

On the hills above, blackened pines and oaks alternate with olive groves and pastures gone up in smoke, in stark contrast to the white wind turbines in the background.

A pair of deer rushes up the slopes where charred turtle shells still lie.

The loss of farm animals is acutely felt in a mainly agricultural area that relies on pasture breeding.

Head of the breeders’ union in the Evros capital of Alexandroupolis Kostas Dounakis said almost half of the region’s farmers have been affected: either their livestock has been burnt or their facilities have been damaged.

“The worst thing is that there are no more pastures. Surviving animals are having trouble finding something to eat,” said the 53-year-old, who lost 150 goats, half his herd.

His warehouse, containing 150 tonnes of animal feed, also burnt down.

Athanassia Pistola’s thoughts wander back to the first days after the disaster.

“We were both devastated, we wanted to give up everything. Then, we thought about the remaining animals, we told ourselves to continue at least for this winter,” the 56-year-old breeder said.

Some of the locals have blamed the disaster on drought, climate change, and poor coordination among firefighters.

But above all, they bemoan the drastic fall in the number of livestock breeders, which has led to the land being abandoned in recent decades.

“The forests have become very dense,” said Dounakis, explaining that without cattle forest grazing, the accumulation of vegetation and fallen leaves and branches create a biomass that is worse than a powder keg.

In the heart of the Dadia park, which houses 360 species of plant and 200 different species of bird, long tree trunks have been placed horizontally as a bulwark against soil erosion.

It is a necessary emergency measure to facilitate the rebirth of the forest, specialists said.

“Mediterranean ecosystems tend to regrow,” said biologist Sylvia Zakkak with the local Environment and Climate Change Agency.

“We will observe the evolution of the fauna and flora and intervene if necessary,” she said.

Most importantly, the park also shelters 36 of Europe’s 38 raptor species including the emblematic black vulture.

Fortunately, the vultures have reappeared after the fire.

“Special platforms will be installed to help them rebuild their nests,” Zakkak said.

But other birds of prey including hawks and owls, in addition to other species that need thick foliage to nest, are more vulnerable to the fire damage because the forest could take decades to repair.