ANN/THE KOREA HERALD – Despite a consistent decline in reader engagement, independent bookstores in South Korea are not only surviving but thriving.

“Over the last decade, we’ve witnessed a significant drop in the percentage of people picking up a book each year, plummeting from 72.2 per cent in 2013 to just 46.9 per cent in 2021. However, considering the diverse ways people now access information, the situation may not be as dire as it appears,” explained Baek Won-geun. He has been instrumental in conducting 15 of Korea’s biannual National Reading Surveys since 1993, overseen by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

After his tenure at the Korean Publishing Research Institute, he established the Centre for Societal and Literary Ecosystem Research in 2015, although he won’t be overseeing the 2023 report scheduled for later this year.

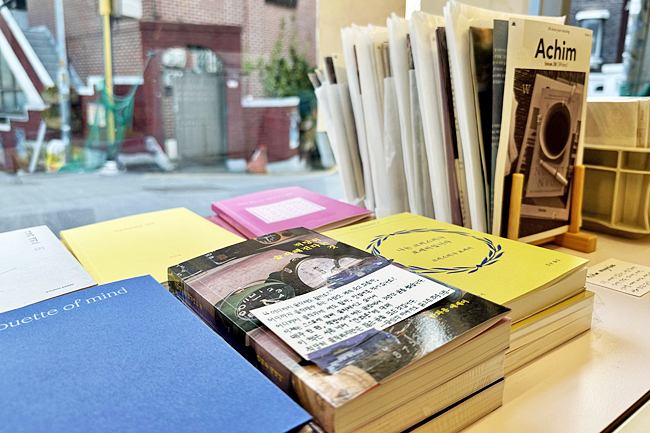

One only needs to meander through Seoul’s bustling streets to witness this paradigm shift, epitomised by the burgeoning indie bookstore scene. These charming brick-and-mortar stores, often sandwiched between imposing commercial buildings, offer curated literary experiences.

Particularly in storied neighbourhoods like Haebangchon in Seoul’s Yongsan district, one finds these repositories of unique titles. From a mere 97 in 2015, the number of indie bookstores across Korea rose to 815 by 2022 – an 8.4-fold rise in just seven years, as recorded by Dongneseojeom, a data analytics firm specialising in this niche sector.

CATERING TO CREATORS

Unlike mega bookstore chains stocked with mainstream titles, these shops curate selections from indie presses, serving both as havens for authors and vital distribution channels. Initially, the indie publishing scene was mostly comprised of young innovators producing visually centric content like posters and postcards. Today, a diverse array of creators contributes novels, essays and travelogues, increasingly blurring the line between indie and mainstream.

Dr Koo Sun-ah, an urban humanities scholar from the University of Seoul, has championed the indie bookstore scene since 2016 with her establishment, Chaegbangyeonhui. Her expertise lies in understanding the world of indie bookstores and their influence on urban and societal dynamics.

She is an essayist herself, having published works like Writing in the Modern Age with Insights from Today’s Writers, and The Perfumed Pages of Jeju.

A prime illustration of a successful self-writer is Baek Se-hee’s I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki.

After a decadelong struggle with mental health, Baek turned six months of therapeutic insights into this book. Eager to share her journey, she successfully crowdfunded KRW15 million on the platform “tumblbug” to self-publish.

Soon after, a boutique publisher spotted the book’s potential. By mid-2018, it had seen 11 reprints and consistently ranked high on bestseller lists. Last year, Bloomsbury, the British publisher behind Harry Potter, released an English edition and sold an impressive 100,000 copies by year-end.

At the same time, Pyo Jeong-hoon, a publishing industry commentator known for his incisive evaluations of books, authors and publishing trends, regards the success of titles like I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki as an outlier. While he appreciates the indie bookstore movement, he remains an advocate for reading as a contemplative exercise and questions its overall influence on Korea’s reading landscape.

TENUOUS FUTURE

Koo also acknowledges the inherent limitations of the indie bookstore model. The cosy and personalised ambiance of these shops, coupled with their typically smaller size, can restrict their audience reach and overall profitability, despite their increasing numbers.

Koo explained that the relatively low 15 per cent closure rate of indie bookstores, as reported by data firm Dongneseojeom, isn’t necessarily indicative of their financial robustness. She highlights that many indie bookstore owners either have alternative income sources or venture into the business driven by motives other than financial gain.

Employee at Storage Book & Film located near Haebangchon Jeong Sora, observed varied customer behaviours. “Many folks wander in, sometimes drawn by an Instagram post, and take their time leafing through various titles before settling on one. From my experience chatting with some, it’s clear some aren’t your everyday readers. It just goes to show the intimate pull indie bookstores and authors have,” she said.

But Jeong was candid enough to admit that some customers were more preoccupied with snapping photos than engaging with the literature.

Independent bookstores have long faced criticism for being more like photogenic backdrops than centres for reading. Koo Sun-ah sees this as a natural shift in usage.

“Spaces, including bookstores, will either become expansive, theme park-like entities, or remain as intimate individualised spots.”

However, the future of these cherished venues is tenuous. The 2021 industry report by the Publication Industry Promotion Agency of Korea highlighted that while the birth of new independent bookstores is steady, many can’t sustain their leases past two years. The same data from Dongneseojeom revealed that from 2015 to 2022, out of 1,031 new indie bookstores, 216 closed, leaving 815 in operation.