PAJU (AFP) – Near the heavily fortified border that divides North and South Korea, a monitoring device is working 24/7 – not tracking missiles or troop movements, but catching malaria-carrying mosquitoes that may cross the border.

Despite its advanced healthcare service and decades of determined efforts, achieving “malaria-free” status has remained elusive for South Korea, largely thanks to its proximity to the isolated North, where the disease is prevalent.

The South issued a nationwide malaria warning this year, and scientists say climate change, especially warmer springs and heavier rainfall, could bring more mosquito-borne diseases to the peninsula unless the two Koreas, which remain technically at war, cooperate.

The core issue is the demilitarised zone (DMZ), a four-kilometre (km)-wide no man’s land that runs the full length of the 250km border.

The DMZ is covered in lush forest and wetlands, and largely unvisited by humans since it was created after the 1953 ceasefire that ended Korean War hostilities.

The heavily mined border barrier area has become an ecological refuge for rare species – an Asiatic black bear was photographed in 2018 – and scientists said it is also an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes, including malaria carriers that can fly as far as 12km.

The DMZ has stagnant water plus “plenty of wild animals that serve as blood sources for mosquitoes to feed on in order to lay their eggs”, said staff scientist Kim Hyun-woo at Seoul’s Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

South Korea once believed it had eradicated malaria, but in 1993 a soldier serving on the DMZ was discovered to have been infected, and the disease has persisted ever since, with cases up nearly 80 per cent last year to 747, from 420 in 2022.

“The DMZ is not an area where pest control can be carried out,” environmental biology professor Kim Dong-gun at Sahmyook University in Seoul told AFP.

As mosquito populations increase, more malaria carriers are “feeding on soldiers in the border region, leading to a continuous occurrence of malaria cases there”, he said.

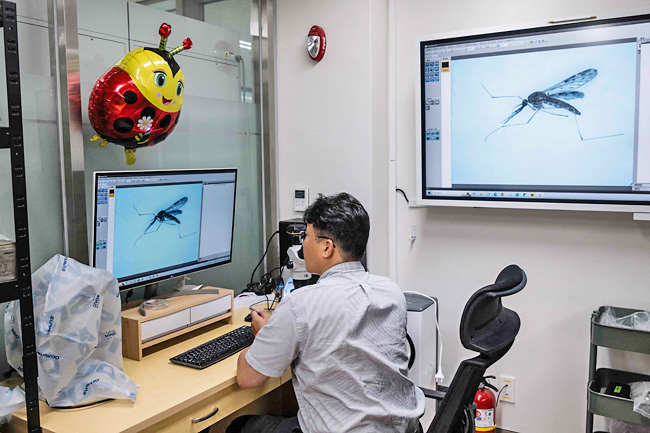

The South Korean health authorities have installed 76 mosquito-tracking devices nationwide, including in key areas near the DMZ.

North of the border, malaria is more widespread, with the World Health Organization (WHO) data indicating nearly 4,500 cases between 2021 and 2022, with the country’s extreme poverty and food insecurity likely exacerbating the situation.

“North Korea is a republic of infectious diseases,” former North Korean doctor Choi Jung-hun, who defected in 2011 and now works as a physician in the South, told AFP.

Choi said that even though he lived in the north of the country, he had treated malaria patients, including a North Korean soldier who had been based near the border with the South.

Outdated equipment like old microscopes hampers early and accurate malaria diagnoses, Choi said, while malnutrition and unhygienic water puddles and facilities make residents especially vulnerable to the disease.

The severe flooding that struck the North this summer could make things worse. In Pakistan, catastrophic flooding in 2022 contributed to a fivefold increase in malaria cases year-on-year.

“North Korea continues to rely on outdated communal outdoor toilets. Consequently, when floods occur, fecal water overflows, resulting in the swift spread of (all kinds of) infectious diseases,” Choi told AFP.

In the last decade, around 90 per cent of South Korea’s malaria patients were infected in regions near the DMZ, official figures show – although rare cases have occurred in other areas.

Shin Seo-a, 36, was diagnosed with malaria in 2022 after being hospitalised with recurring high fevers, but she had not visited a border region that year before getting sick.

“I have no recollection of being bitten by any insects,” she told AFP of the period before she became ill.

Doctors initially thought she had a kidney infection and it took around 10 days before she was finally diagnosed with the mosquito-borne disease.

Having malaria felt like “I was being stir-fried on a really hot pan,” she told AFP, saying it was so painful that in tears, “I once even begged the nurse to just knock me out.”

Malaria on the Korean peninsula is caused by the parasite Plasmodium vivax and is known to be less fatal than tropical malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum, which affects many African countries.

Even so, after contracting malaria Shin developed Nontuberculous mycobacteria, a lung disease that typically affects individuals with a weakened immune system.

“Malaria is a truly terrifying disease,” she told AFP, adding that she hoped more could be done to prevent its spread.

But with the nuclear-armed North declaring Seoul its “principal enemy” this year and cutting off contact, as it rejects repeated offers of overseas aid, cooperation on malaria looks unlikely.