ANN/THE STRAITS TIMES – Renowned cartoonist Lat’s initial encounter with the transformative impact of art didn’t unfold within the confines of a museum, instead, it blossomed on the pages of daily newspapers, particularly through comic strips.

At the age of six, long before he could decipher words, Lat immersed himself in the vibrant visuals, relying on friends to narrate the accompanying dialogues.

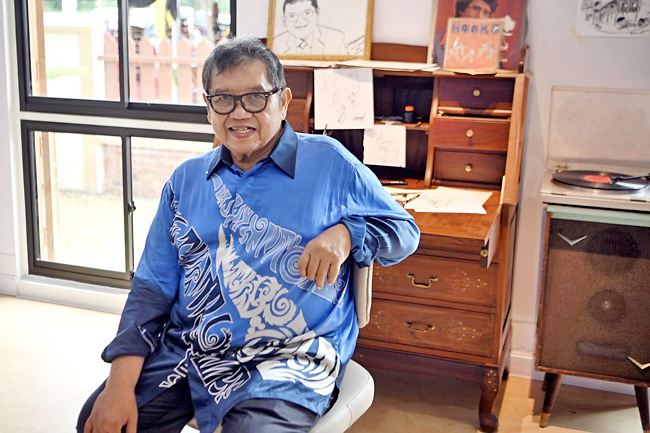

“And what fun it was,” the 72-year-old recalled over the telephone from Ipoh, Perak where he now lives.

“We laughed, and we would laugh again the next day. Later, when the teacher told us to draw anything, I drew funny comics.”

Short for bulat, or Bahasa Malaysia for anything round or moon-shaped, Lat was the village moniker given to him by his friends.

His birth name is Mohammad Nor Khalid, though it has been a while since anyone called him that.

Even his father and grandmother called him Lat. It is an indication of the milieu in which he grew up in Perak, and which he infused in so much of his cartoons later as a column cartoonist for English daily New Straits Times.

For 40 years on Mondays, Tuesdays and Saturdays, readers in Malaysia, and even Singapore and Indonesia, would look forward to his cartoons.

In 1994, the Sultan of Perak bestowed on him the honorific title of Datuk and, in 2023, recognised him as a Royal Artist (Seniman Diraja).

Lat is one of the keynote speakers at 2023’s Singapore Writers Festival, a prestigious spot also given to Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sympathizer (2015) Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Together with Indonesian artist Toni Masdiono and CT Lim, Singapore’s country editor for the International Journal of Comic Art, he will also discuss the lives of South-East Asian cartoonists in a panel moderated by editor at Asiapac Books Viency Lee.

Lat traces much of his humourous worldview back to his village days, an idyllic time he revisited in his international best-seller The Kampung Boy (1979), a graphic novel that was translated into Japanese and French, among others.

In it, mop-topped kids are dwarfed by items of the adult world, and the traditional Perak house, with its elevated foundation, became recognisable by kids as far away as in the United States.

Lat says: “If someone was dark, we called him itam. If your name is Yusoff, we called you Yuchop. It was not so formal and we were all joking around, shouting around. It was our way of keeping boredom at bay.”

Asked if drawing was something he, too, did to stave off boredom, he immediately turns serious.

“Drawing is another thing, like music, like sports. People are born in this world with something. Some can sing, or write stories, poetry. I drew.”

His father, an army clerk, recognised his talent and threw him papers he brought back from the office so Lat could keep practising.

Later, after a short stint as a crime reporter at Bahasa Malaysia daily Berita Harian in Kuala Lumpur, Lat’s editors also saw his gift and told him to draw instead.

He was sent cross-country to Kelantan and Penang, where his boss was from. There, he was told that people were more stingy and he should always pay attention to bullock carts.

Lat says the key to being able to observe the slice-of-life scenes he is known for is to live ordinarily and cheaply.

When he first moved from his village to Kuala Lumpur, he struggled with living in a big city and the general feeling of being invisible, until one day he saw celebrities – a singer and a newscaster – both waiting for the bus without any fuss.

“That’s when I realised I was nobody and that I had a long way to go,” reflected Lat.

“Nowadays, people sing a song and think they are a superstar, or print their own book and think they are a writer. I just did what people do normally. I said ‘Let’s play football, let’s go take a bus ride.’ They were things that were relevant to everybody.”

In some ways, this allowed him to find the village in the big city and, almost inadvertently, his works became a byword for multiracial living. Kleenex tissue boxes even featured some of his work in its #SoftisStrong campaign to get Malaysians to be kinder to one another.

Lat now spends most of his time in his room “drawing, reading whatever I can get my hands on, and watching old Japanese and Italian movies”.

He retired because he no longer recognises the politicians and celebrities he used to have to draw.

“As I grew older, I paid more attention to myself and my family.”