JAKARTA (ANN/THE JAKARTA POST) – Under the leadership of the Indonesian Industry Ministry, a silica industry road map is set to be finalised by the conclusion of the upcoming year with the primary purpose of providing guidance for industrial advancement from 2025 to 2035.

Its ultimate goal – establishing the capacity for domestic silicon wafer production within this designated timeframe.

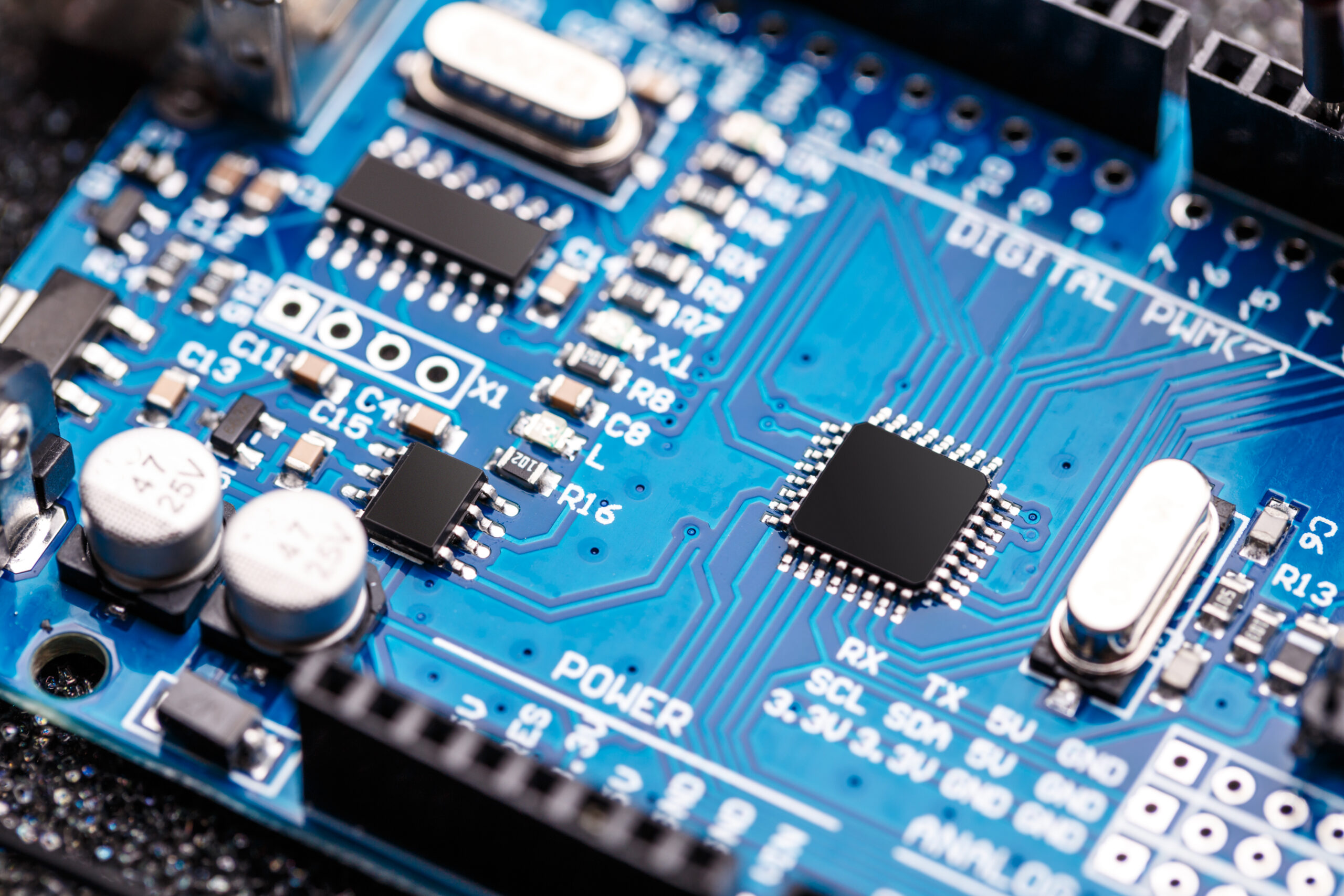

Indonesia has initiated the formulation of the strategic plan to foster the growth of its silica sector, intending to use it as a foundational step towards establishing a domestic microchip industry.

However, it’s worth noting that certain fellow ASEAN nations have significantly outpaced Indonesia in the competitive pursuit of semiconductor investments.

“Silica (industry development) as a national program will only receive its budget allocation […] in 2024,” Wiwik Pudjiastuti, a director in the Industry Ministry, told the source on Tuesday.

The road map will cover six strategic aspects, namely a review of Indonesia’s resources, the actors involved, existing and necessary manufacturing technology, policies, human capital and the market potential, both domestic and foreign.

Silica is the raw material for silicon wafers, and the latter are the building blocks of semiconductor chips as well as photovoltaic modules, commonly known as solar panels, meaning its processing could serve two different manufacturing industries.

According to 2021 Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry data, Indonesia has some 330 million tonnes of silica sand reserves, with a far bigger resource potential of 2.1 billion tonnes. Wiwik explained that this number was subject to change through future surveying.

However, the resource alone does not translate into a strong competitive advantage, given that silica can be found in virtually any country. Hence, the government cannot bank on that to attract investment.

Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (Indef) executive director Tauhid Ahmad said that left Indonesia with just one more proposition, namely the strength of its domestic market, supposing it has demand for silicon wafers.

“If it’s solely for export, I think it will be difficult,” Tauhid told the Post on Monday.

Creating a market for silicon wafers will be part of the government’s road map, according to Wiwik.

Obvious off-takers for solar panels are state-owned utility firm PLN and private companies betting on Indonesia’s energy transition, while semiconductors could be sold to manufacturers like automakers, which struggled to secure the critical components amid a global chip shortage last year.

Attracting semiconductor investment was “quite possible” for Indonesia, Tauhid said, especially if the country could offer “very cheap prices”.

Concurring, Economist Intelligence Unit analyst Laveena Iyer told the source on Tuesday that there was no doubt about “foreign investor interest in Indonesia’s budding chip industry”, pointing to the Indonesian operations of Germany’s Infineon as a case in point.

Semiconductors differ widely in complexity, ranging from simple ones used in household appliances to sophisticated ones for supercomputers or high-end military equipment. The latter underscores the sensitivity of the technology and has prompted some countries to restrict trade in semiconductors.

In recent years, the United States has been pushing US-based companies to move production out of China, a country Washington sees as a strategic competitor for global influence.

Vietnam is increasingly turning into a preferred destination for US manufacturers.

US President Joe Biden made a state visit to Hanoi on September 10 and announced investment in new semiconductor design centres in Ho Chi Minh City by Synopsys and Marvell, a USD1.6 billion chip-packaging facility near Hanoi that is scheduled to open in October as well as a US-Vietnam chip partnership.

Another source wrote on Monday that Vietnam had dipped its feet in the field since the late 1970s and had been rolling out incentives since 2015, giving it a decades-long head start on Indonesia.

“It will certainly be hard” to catch up with Vietnam in this industry, Tauhid said. Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Jakarta researcher Muhammad Habib agreed that Indonesia was far behind.

He went on to say that chip companies saw Vietnam and Malaysia as “more optimal” places for chip production for various reasons.

“Indonesia cannot ensure regulatory certainty. One year it puts one regulation in place, and then in another year, it suddenly changes course,” Habib told the source on Monday.

He added that layers of bureaucracy drove up the cost of production in Indonesia and corruption was a potential factor that may hamper investment in Indonesia’s semiconductor industry.

“The assumption that we can get a US (partnership) is too imaginative, unaligned with reality on the ground,” said Habib when asked about the odds of Indonesia following in Vietnam’s footsteps.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo declared that Indonesia was ready to become part of the US semiconductor supply chain when he met US Vice President Kamala Harris earlier this month.

Given the dispersed nature of semiconductor supply chains with different countries specialising in specific components, Iyer said Indonesia should consider enticing South Korea, Taiwan, Japan and the Netherlands to get involved in the country’s chip industry plan.

“We believe that competing external powers will continue to court Indonesia,” Iyer answered when asked if it was possible to attract US investment in this development, given Indonesia’s close ties with China.

Statistics Indonesia (BPS) revealed in 2022 that the potential import substitution value for silicon wafers amounted to USD17.7 million, USD120 million for semiconductors, USD6.2 million for disassembled solar cells and USD65.9 million for assembled solar cells.