Ron Charles

THE WASHINGTON POST – The outrageousness of the case against Mahmood Hussein Mattan still burns: In 1952, Mattan, a former merchant seaman, was arrested for slitting the throat of a shopkeeper in Cardiff, Wales. His murder trial was riddled with lies and suppressed evidence. His own defence lawyer described him in court as a “semicivilised savage”.

And then Mattan was hanged.

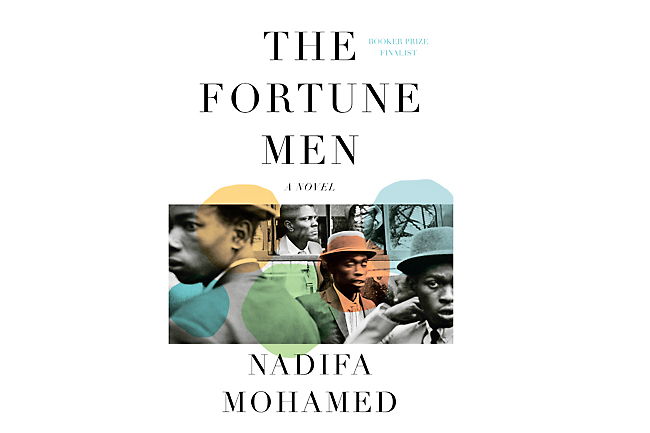

For more than four decades afterward, the wheels of justice turned excruciatingly slowly. But in 1998, the Court of Appeal overturned Mattan’s conviction and awarded his family GBP725,000 as compensation. Although there can be no restitution for the unjustly executed man, his ordeal is the subject of an extraordinary novel that insists on his innate value and exposes the system that killed him. The Fortune Men, by a Somali-British author Nadifa Mohamed, was shortlisted for last year’s Booker Prize.

As a work of historical fiction, Mohamed’s novel is equally informative and moving. While the details of her story are drawn from news accounts and court records, the interior portraits stem from her own deeply sympathetic imagination. The resulting confluence of fact and fiction provides a damning indictment of judicial racism. But with a vision that exceeds this one tragic case, The Fortune Men also plumbs the existential plight of so many similar victims.

The immediate allure of the novel is the vibrancy of Mohamed’s prose, her ability to capture the complicated culture of Cardiff and the sound of tortured optimism. Born in British Somaliland, her doomed hero, Mahmood, came to Wales as a merchant seaman – one of the vast army of men drawn to the work after World War II. But when the story opens, he hasn’t sailed for three years. These days the bustling area of Cardiff’s Tiger Bay comprises his whole world, a realm of opportunities constantly out of reach.

“It’s hopeless,” he thinks at age 24. The White employers of this town will “only ever see him like one of those grimy coolies in loincloths, or jungle savages, shrieking before their quick, unmourned deaths – or at best, a tight-lipped houseboy.”

Hovering close to Mahmood’s thoughts, The Fortune Men conveys the mix of deprivation and harassment that exhausts unemployed labourers. “He’s sick of dealing with the police,” Mohamed wrote, “feeling the rattle of their bracelets around his wrists, sharing mattresses with the city’s vagrants and derelicts. He’s too old for this and they, the police, are beginning to hate him; there’s something personal brewing there, they speak his name too freely, and want to believe he is capable of anything”.

Reduced to petty crimes and working on “poky little boilers in prisons and hospitals”, he repeatedly wastes his meager savings and then wonders why his estranged wife finds him so exasperating.

“Mahmood still can’t accept that he is just another uncared-for man eating from a plate on his lap in the solitude of a cold rented room,” Mohamed wrote. “Meals are just another thing he has to do by himself, for himself. Everything with just his own damned hand.”

There’s the crux of Mohamed’s artistry: Her clear-eyed acknowledgment of this man’s self-pity runs parallel to her piercing exposure of his society’s relentless, enervating prejudice.

Yes, she suggested, Mahmood is a flawed, sometimes foolish man – which is to say, he’s an actual human being. And his humanity is eventually what makes him so vulnerable to the machinations of corrupt policemen.

The horrific finale of The Fortune Men is never in doubt, but for more than 200 pages Mohamed still creates a sharp sense of suspense by pulling us right into Mahmood’s world as his life tilts and then crashes. From his point of view, it’s an unthinkable calamity. After all, he was arrested merely for fencing a shoplifted coat. He can’t fathom why his interrogators keep mentioning a murdered shopkeeper. Confronted with fabricated testimony, “Mahmood stumbles, his English is fracturing, words of Somali, Arabic, Hindi, Swahili and English clotting at once on his tongue.”

To the officers determined to convict him, he becomes a wild man, sputtering gibberish.

Despite Mohamed’s fidelity to the knocks and humiliations endured by Cardiff’s immigrant labourers, there’s a natural grandeur to her portrayal of this ordinary man caught in the city’s gears. Readers will hear echoes of Dostoevsky and Kafka in her re-creation of this nightmare. “You’ll hang, whether you did it or not,” someone tells Mahmood as he sails on toward execution like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Convinced that he’s a noble outlaw, a principled thief, he can’t entirely admit the peril of his situation. Asked at his arraignment if he needs legal aid to pay for a solicitor to defend him, Mahmood snaps, “Defend me for what? I don’t want anything and I don’t care anything. You people talking crazy. You can’t get me to worrying.” Ironically, he’s so indoctrinated in the mythology of the United Kingdom that he can’t shake his faith that the court will ultimately save him.

The intensity of Mahmood’s tragedy is leavened by a very different tragedy that runs through the novel. In alternate sections, we get to know Violet, the owner of a modest shop in Cardiff.

“Nowhere feels safe any more,” she thinks. What has she and her family won by living in Cardiff, where their store is repeatedly vandalised and robbed? And then – the most devastating outrage of all – Violet’s throat is slit while her sister eats dinner next door. It’s no solace to her family that the police are determined to punish an innocent man.

Listening to the witnesses deliver their false testimonies, Mahmood is aghast at the skewed image of him. “They are blind,” he thinks, “to Mahmood Hussein Mattan and all his real manifestations: the tireless stoker, the elegant Wanderer, the love-starved husband, the soft-hearted father.”