PREAH VIHEAR (AFP) – Eam Orn kneels in a forest in northwest Cambodia, pressing his hands together before an offering of bananas studded with smoking incense, and prays for the return of his land.

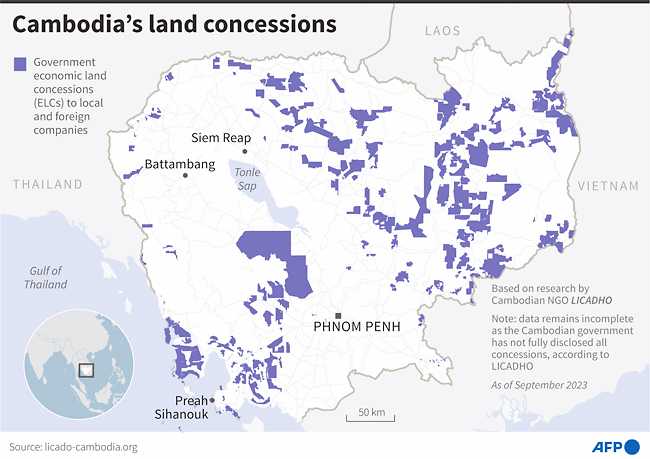

He is one of hundreds of thousands affected by economic land concessions (ELCs) – land grants to businesses that experts said have driven deforestation and dispossession.

From 2001 to 2015, a third of Cambodia’s primary forests – some of the world’s most biodiverse and a key carbon sink – were cleared, and tree cover loss accelerated faster than anywhere else in the world, according to the World Resources Institute.

The government halted ELCs in 2012, but a new grant has raised fears the moratorium could be over, even as Cambodians like Orn struggle with the policy’s legacy.

“If the state wants to compensate me with money, I don’t want it,” the wiry farmer told AFP in some of the last remaining forest near his village, Praeus K’ak. “I only want my land.”

Orn, of Cambodia’s ethnic Kuy people, lives surrounded by more than 40,000 hectares of ELC.

He lost eight hectares when the government granted it to subsidiaries of China’s Hengfu Group in 2011, for a sugar processing facility touted as one of Asia’s largest.

It was supposed to employ thousands, but today its chimney stacks stand silent behind locked gates, and air blows in through broken windows.

Reached by phone, a Hengfu employee in China confirmed the factory was closed, but said only top-level management knew why.

Cambodia formalised ELCs in 2001 with legislation allowing recipients to clear land for “industrial agricultural exploitation”.

Large tracts have, however, been handed to rubber, sugar and paper firms since at least 1993, according to the United Nations (UN).

A lack of transparency makes the scale hard to quantify, though Cambodian rights group LICADHO has tracked at least 313 concessions, covering more than 2.2 million hectares.

The country’s protected areas, where commercial development is legally prohibited, have not been spared. ELCs covered 14 per cent of them by 2013, according to non-governmental organisation (NGO) Forest Trends.

Rampant deforestation in Cambodia pre-dates ELCs, but the concessions have been a “predominant driver” since their introduction, according to a 2022 study in journal Scientific Reports that found a clear correlation between forest loss rates and ELC expansions.

And deforestation is not the only consequence.

“Wherever there are ELCs, there are (land) disputes,” Pen Bonna, coordinator for rights group ADHOC in Preah Vihear province, told AFP.

Cambodia’s land records were largely destroyed by the communist Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s and after its fall people often settled without legal title.

The 2001 law offered a path to ownership, but the complex process means few have obtained it, leaving villagers like Orn vulnerable to land grabs, despite frequent condemnation by rights groups and the UN.

“My family’s livelihood and income has gone down… I’m older and can’t work as a labourer,” the father of seven said.

He took out bank loans for food and clothing, and even worked at the sugar factory before it closed.

“If we did not go, we had nothing to do.”

Thoeun Sophoeun, 29, also took out loans after losing around six hectares of farmland and access to the surrounding forest that once provided crucial additional sustenance.

“We could enter the forest and easily bring meat and food back home but now it’s all gone,” said the mother of two.

ELCs were long enthusiastically championed by former Cambodian leader Hun Sen as a way to bolster the country’s economic development.

“More Cambodians will be rich. I want to see more Cambodian millionaires. There are many of them in China,” he said at the opening of a sugar factory on an ELC in 2012.

But that same year, faced with growing land conflicts and admitting the risk of a “farmers’ revolution”, Hun Sen announced the ELC moratorium. He pledged the government would seize land from firms who cleared trees for sale or failed to develop their plots.

In Praeus K’ak, little has changed.

Since the factory closed, villagers including Orn and Sophoeun have crept back onto farmland. “We farm with fear, because the state has not made any announcement,” said Sophoeun. “We don’t know whether they will come and take it back.”

Locals said some company workers have leased plots to outsiders to farm, violating the ELC agreement, but the government has not acted.

In January, LICADHO sounded the alarm over what it called a new ELC, citing a March 2022 letter authorising the transfer of nearly 10,000 hectares in northeastern Stung Treng province.

Locals told AFP land has already been seized for a road, and described intimidation and the arrest of a villager who challenged the concession.

“They don’t let us grow anything,” said Tha, who asked not to be identified by his full name to avoid retaliation.

“They have threatened to arrest us one by one.”

Licadho operations director Am Sam Ath said the group had identified other new land grants, including inside Botum Sakor National Park.

“Now they use words like long-term lease,” he said. But “it is similar to ELCs”.

He warned of “doom for forests” if the policy resumes, with little hope of transparency or monitoring.

In Praeus K’ak, Orn worries that his grandchildren are growing up with no memory of his people’s sacred forests and no knowledge of the animals that once populated them.

“We lost worship forests, we lost income… I’m very worried about our identity,” he said, calling on others to fight new concessions.

“If it’s lost, it’s lost forever.”