THE WASHINGTON POST – Humans have filled the world’s oceans with more than 170 trillion pieces of plastic, dramatically more than previously estimated, according to a major new study.

The trillions of plastic particles – a “plastic smog”, in the words of the researchers – weigh roughly 2.4 million metric tonnes and are doubling about every six years, according to the study conducted by a team of international researchers led by Marcus Eriksen of the 5 Gyres Institute, based in Santa Monica, California in United States. That is more than 21,000 pieces of plastic for each of the Earth’s eight billion residents. Most of the pieces are very small.

The study, which was published in the PLOS One journal, draws on nearly 12,000 samples collected across 40 years of research in all the world’s major ocean basins. Starting in 2004, researchers observed a major rise in the material, which they said coincided with an explosion in plastics production.

The findings pointed towards both the vast amount of plastic that is flowing into the world’s oceans and the degree to which it is journeying long distances once in the water. The study may deliver a jolt of energy to United Nations (UN) talks to reduce global plastics pollution that started last year.

“This exponential rise in ocean surface plastic pollution might make you feel fatalistic. How can you fix this?” said founder of the 5 Gyres Institute Eriksen, a non-profit group that works to study and fight ocean plastics pollution.

“But at the same time, the world is negotiating a UN treaty on plastic pollution,” Eriksen said.

The weight of all that plastic is equivalent to about 28 Washington Monuments.

The samples that were studied end in 2019, so several more Washington Monuments of plastic are likely to have dropped into the sea since then.

Eriksen and the other researchers travelled the world’s oceans to collect samples, combed the archives of previous researchers for unpublished data and incorporated other peer-reviewed studies into their analysis. They used new models to estimate the quantity of plastic, leading to sharply revised, higher numbers compared with a 2014 study by Eriksen and some of the same researchers that used a much smaller set of data.

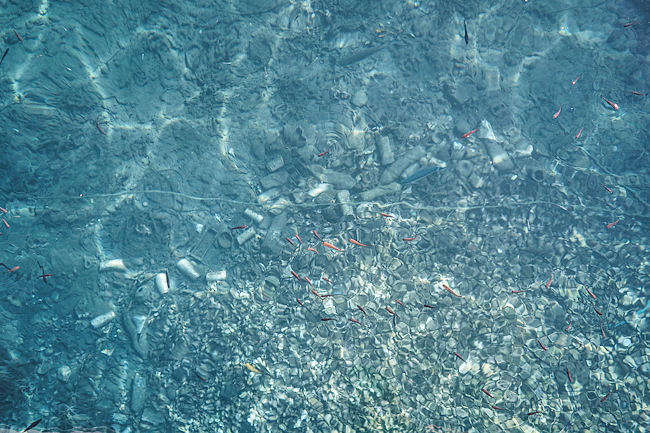

Only 10 per cent of the plastic ever made has been recycled. The material that doesn’t make it into landfills can get swept into rivers or directly into oceans. It slowly breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces, known as microplastics, which are less than five millimetres in length and can be eaten by marine life. Plastic has been found near the summit of Mount Everest and inside the deepest point on Earth, the Mariana Trench – as well as in the human bloodstream.

The study examined plastic samples over 40 years starting in 1979. The researchers found a fluctuating amount of plastic in the samples until 2004, when the numbers started to skyrocket.

The increase in plastic particles in the oceans corresponds to a previously observed increase of plastic on global beaches over the same time period, they noted.

“These parallel trends strongly suggest that plastic pollution in the world’s oceans during the past 15 years has reached unprecedented levels,” the study said.

The data includes samples from the world’s five major gyres, or current systems, which sweep particles from inhabited areas to create large collections of refuse.

The best known of these is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, where plastics float slightly below the surface.

In looking at samples, the researchers concentrated on the North Atlantic and North Pacific ocean basins, partly because they have been studied more frequently over the decades and are where greater concentrations of the world’s population lives.

But high concentrations of plastics were found everywhere.

Global negotiators hope to complete the plastics treaty by 2024.

It would regulate all aspects of the life cycle of plastic, including the kinds of chemicals that go into it and whether it’s easily recyclable.

Anti-pollution campaigners said it is far easier to deal with plastic before it enters waterways than it is to clean it up afterward.

The study’s lead author Eriksen, said research into plastics pollution had in recent years started to shift away from oceans and move farther upstream, to rivers and other waterways, as advocates struggled to understand the issue at its origin.

“The plastic pollution, it’s in every biome,” he said. “It’s not just in oceans anymore.”