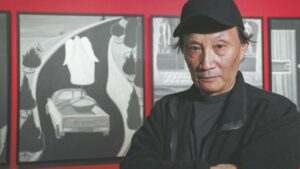

BEIJING (ANN/CHINA DAILY) – With no formal training, artist captures Shanghai lives in his stories and illustrations, blending realism with a bit of absurdity, Li Yingxue reports.

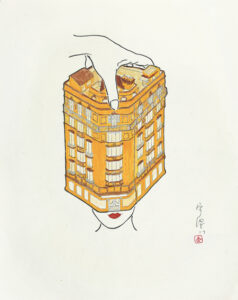

A tray lifts Jing’an Monastery, a single hand holds the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, and chopsticks delicately turn the pages of the novel Fan Hua (Blossoms) — these whimsical images come from the imagination of artist Jin Yucheng, who brings his hometown of Shanghai to life through a distinctive artistic vision.

Jin is better known as a celebrated writer, particularly for the novel that won him the Mao Dun Literature Prize in 2015.

While Fan Hua gained widespread recognition over the past decade, fueled by literary accolades and a TV adaptation by famed director Wong Kar-wai, Jin has devoted much of his time to painting.

Much like his literary works, Jin’s paintings are marked by his unique style — each piece tells a story that blends realism with a touch of absurdity — a fantastical narrative brought to life with every brushstroke.

Starting point

Born in 1952 in Shanghai, Jin spent his childhood in his grandfather’s villa on South Shaanxi Road. At 17, he moved to Heilongjiang province to work on a farm. Upon returning to Shanghai, he was employed as a machinist in a watch factory and began writing in his spare time. In 1988, he became an editor at Shanghai Literature, a position he held until his recent retirement.

Fan Hua was published in 2012.

Reflecting on why he wrote the novel, Jin recalls his frustration upon reading online gossip that targeted individuals by name. Determined to focus on the lives of ordinary, nameless people, he set out to capture their stories.

In the novel, Jin paints a rich portrait of Shanghai, drawing on his observations and experiences to depict the city’s daily life — details also featured in his artwork. For Jin, painting and writing serve a similar purpose: to preserve the lives of ordinary people.

Jin’s foray into painting began with Fan Hua. When the novel was serialized in Harvest magazine, he created four maps as illustrations. Later, as it was being prepared for stand-alone publication, the editor suggested he add more illustrations to clarify key elements like buildings, scenes and clothing.

Jin adds: “Only through visuals can we capture aspects that words cannot reach. The structure of old lane houses — their upstairs and downstairs — only a drawing can make it instantly clear.”

The illustrations in the novel received positive feedback from readers, boosting Jin’s confidence and motivating him to continue painting.

Jin’s foundation in painting comes from mechanical drafting. In the 1970s, while staying at a farm dormitory in Heilongjiang, he found a worn architectural pen-drawing tutorial, which became his key reference.

At the watch factory in Shanghai, he spent six months learning mechanical drafting, laying the groundwork for his art.

With no formal art training, Jin’s works break from convention, developing a unique style that mirrors the intricate, meaningful structure of his novels.

Regarding the narrative and metaphorical elements that permeate his work, Jin acknowledges that his lack of formal training in lines, light and color often leads him to create stories or add complexity to the details. He aims to incorporate elements that capture attention and shift focus away from questions of technical training or color accuracy.

“I don’t try to make my paintings look realistic. I want to express my ideas or blend them. It’s like playing,” he adds.

Drafting dreams

Jin’s approach to painting is rooted in storytelling. Without a clear narrative behind the work, he loses interest in creating it.

His painting An European Building tells the story of a building he passed daily during middle school. It always intrigued him, but he struggled to find a way to depict it. The breakthrough came when he imagined a hand lifting the building, sparking his creative process.

“People often wonder whether the hand is lifting the building or setting it down. This ambiguity is one of the hallmarks of my style,” Jin says.

The image of the horse appears frequently in Jin’s artwork, a reflection of his earlier experiences in rural Heilongjiang. “The horse has played a pivotal role in advancing history, as there’s a saying that humanity entered the civilized world with the help of horses. It’s an especially endearing symbol. In Chinese culture, we also have many positive expressions related to horses.”

Jin reflects on his childhood education, comparing it to the “little cat catching fish” concept, where the focus is solely on fishing, with no room for distractions like picking flowers or chasing butterflies.

He now realizes this mindset can limit his potential. “I can write and paint,” he says. “I can pick flowers, chase butterflies, and try new things. Life has no fixed path. Everyone can switch careers as long as they’re interested. When I write novels, I feel I am full of holes, but when I paint, I feel like I’m still growing, like a child just starting to learn. It’s an incredibly enjoyable process for me,” he adds.