Dougless K Daniel

AP – Leo Tolstoy’s adage that “each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” is inverted in the making-of film book genre: They are all unhappy in the same way.

Each features a suffering auteur beset by money men, clashing actors, blown schedules and more, all while threatened with professional extinction.

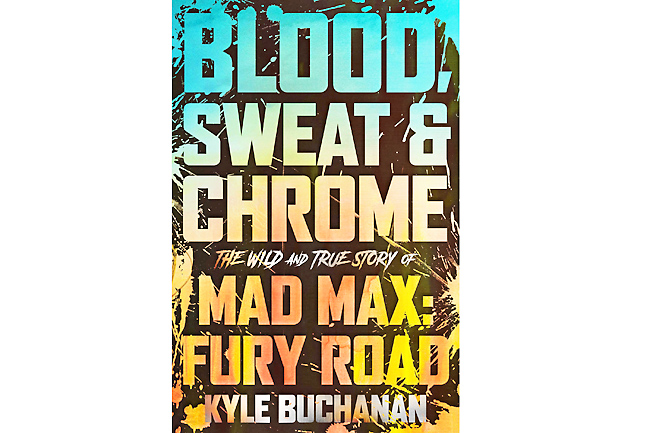

Fortunately, Kyle Buchanan’s oral history Blood, Sweat and Chrome: The Wild and True Story of Mad Max: Fury Road pulls away from clichés by tossing the keys to the filmmakers themselves.

The pop culture reporter for The New York Times assembled scores of voices that rev up a narrative that will excite Mad Max fans specifically, and entertain film buffs generally, on how ideas are realised as epics.

Reaching back to the late 1970s, the filmmakers recount how an Australian ER doctor, George Miller, worked double-shifts as an EMT to fund his first feature film, Mad Max (1979), a violent revenge tale where law-and-order yields to biker and hot-rod gangs as the Outback falls into anarchy.

Fuelled by vivid characters and elaborate car crashes, the dystopian thriller found a worldwide cult audience to propel Miller and his drama school discovery, Mel Gibson, to fame and fortune.

Instead of simply creating a more-of-the-same sequel, Miller studied enduring protagonist archetypes in sources like Joseph Campbell to create an entire mythos for his post-apocalyptic wasteland. Max followed this antihero’s journey in The Road Warrior (1981) and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) before Gibson exited for good to attain the peak, for a while, of popular and critical success in acting and directing.

However, the calling to reanimate the Max character persisted for Miller as different reboot ideas, including a TV series, languished at the emerging intersection of movies, comics and long-form television. By the mid-1990s, he decided to make another feature film, envisioning “one long chase” in which Max reluctantly teams with a female warrior, Furiosa, to rescue The Wives, five young beauties imprisoned as breeding stock for Immortan Joe, the wasteland’s tyrant.

Collaborating with writers and comic illustrators, Miller allowed his concept to be captured in thousands of storyboards instead of a conventional script.

A drama teacher fleshed out the motivations and evolutions of the characters. According to Miller, developing these detailed backstories was “the only way you have a chance for the movie to feel coherent because otherwise it’s just too crazy”.

Ironically, it was the financial success of his family films, Babe and Happy Feet that enabled Miller to shepherd his Hell-on-Earth vision past a variety of studio obstacles, economic slowdowns and location disasters to begin shooting Mad Max: Fury Road in the summer of 2012.

During the previous years of gestation, Miller’s team expanded to an army of concept artists, gear-heads, costumers, make-up artists and stunt persons.

Headliners Charlize Theron and up-and-comer Tom Hardy had high bars to clear – she had to convince as an unglamorous badass while he had to replace an ageing Gibson in the franchise’s title role.

Preparation was nearly as intense as the shoot in Africa’s Namib Desert. The hoard of nameless stuntmen playing The War Boys performed acting exercises and worshipped The Wives in mock rituals.

An expert educated the cast about the impacts of human trafficking. Even the dozens of vehicles custom-built from junk yards had their own backstories, which informed the most minute details never to be seen by the audience.

Buchanan wrote that the film “tackles up-to-the-minute issues like environmental collapse, female empowerment and resource hording” and is “the finest action movie ever made”.

Mainstream reviews agreed to the extent that this third sequel in an action franchise earned multiple critical awards and landed 10 Oscar nominations for 2015, including best picture and best director, and won six.

Not unlike Fury Road Buchanan’s Blood, Sweat and Chrome succeeds largely at the level you choose, summed up best by War Boy Ben Smith-Peterson: “Sometimes you don’t need to know the backstory of a character that doesn’t have any lines… but I don’t know. I’m a stunt guy. I let people set me on fire.”