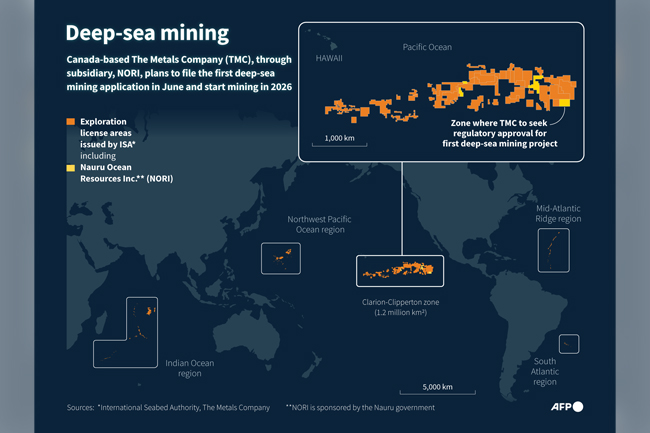

UNITED STATES (AFP) – After more than a decade of negotiations, a new round of talks to finalise a code to regulate deep-sea mining in international waters began yesterday in Jamaica, with hopes high for adoption this year.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), an independent body established in 1994 under a United Nations (UN) convention, has been working since 2014 on the new rules for developing mineral resources on the ocean floor.

The huge task has gathered pace, under pressure from corporate concerns eager to cash in on the untapped minerals.

Canada’s The Metals Company plans to file the first commercial mining license request in June, through its subsidiary Nori (Nauru Ocean Resources Inc), which hopes to extract polymetallic nodules from the Pacific.

Here is a look at the proposed rules, and why they have sparked intense debate: Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the ISA must both oversee any exploration or mining of coveted resources (such as cobalt, nickel, or manganese) in international waters, and protect the marine environment.

For activists worried about the protection of hard-to-reach ocean ecosystems, this twin mandate is nonsensical. Some groups, and more and more countries, are asking for a moratorium on seabed mining. With no consensus, the ISA-led negotiations have continued.

The ISA Council, made up of 36 of the authority’s 169 member states, will spend the next two weeks trying to bridge the gaps on finalising the code. They are working from a 250-page “consolidated text” already riddled with parenthetical changes, and comments on disagreements. But then there are dozens of amendments filed by countries, companies and non-governmental organisations.

Deep Sea Conservation Coalition member Emma Wilson told AFP there were “over 2,000 textual elements that are still being discussed – and that those debates were “not close to being resolved.”

Any entity wishing to obtain a contract to mine the ocean floor must be sponsored by a specific country. Those applications for mining licenses would first go through the ISA’s legal and technical commission, which NGOs say is too pro-industry and opaque.

The commission would evaluate the financial, technical and environmental aspects of the proposed plans, and then make a recommendation to the ISA Council, the final decision-maker.

But some worry that rules already set by UNCLOS would make it too difficult to reject any favourable recommendations. The draft code calls for initial contracts lasting 30 years, followed up with extensions of five years at a time.

Potential mining companies must conduct a survey of the possible environmental risks of their activities, but details on these surveys are still up in the air, with negotiators not yet even agreed on how to define the terms.

More and more countries, along with NGOs, highlight that even the idea of surveying potential impact is effectively impossible, given the lack of scientific data about the zones and some Pacific states insist that the code explicitly state the need to protect “underwater cultural heritage,” but that is under debate.

The mining code under consideration stipulates that each company must pay royalties to the ISA based on the value of the metals.

But at what price? A working group has proposed royalties of anywhere from three to 12 per cent, while African states believe 40 per cent is more just.