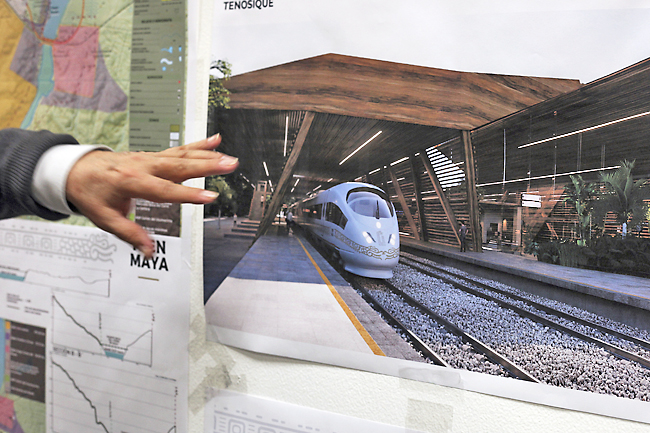

MEXICO CITY (AP) – The Mexican government has invoked national security powers to forge ahead with a tourist train along the Caribbean coast that threatens extensive caves where some of the oldest human remains in North America have been discovered.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is racing to finish his Maya Train project in the remaining two years of his term over the objections of environmentalists, cave divers and archaeologists.

The government had paused the project earlier this year after activists won a court injunction against the route, because it cut a swath through the jungle for tracks without previously filing an environmental impact statement.

But the government invoked national security powers on Monday to resume the track laying.

López Obrador said on Tuesday the delay had been very costly and the decree would prevent the interests of a few from being put above the general good. In November, his government had issued a broad decree requiring all federal agencies to give automatic approval for any public works project the government deems to be “in the national interest” or to “involve national security”.

“I never knew we lived in a country where the President could just do whatever he wants,” said diver Jose Urbina Bravo who filed one of the court challenges.

Activists said the heavy, high-speed rail project will fragment the coastal jungle and will run often above the roofs of fragile limestone caves known as cenotes, which – because they’re flooded, twisty and often incredibly narrow – can take decades to explore.

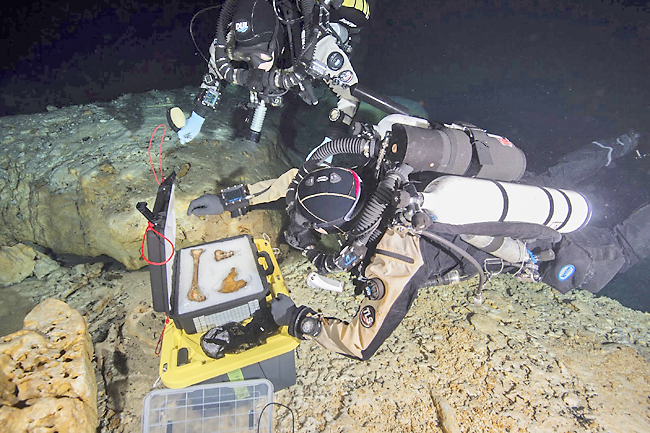

Inside those water-filled caves are archaeological sites that have lain undisturbed for millennia.

The cave systems have mainly been through the efforts of volunteer cave divers working hundreds of metres inside the flooded caverns. Caves along the Caribbean coast have yielded treasures like Naia, the nearly complete skeleton of a young woman who died around 13,000 years ago.

She was discovered in 2007 by divers and cave enthusiasts who were mapping water-filled caverns north of the city of Tulum, where the train line is heading.

“Just in this one stretch of 60 kilometres of planned train tracks, there are 1,650 kilometres of flooded caves full of pure, crystalline water,” said diver and archaeologist Octavio del Rio who has been exploring the region for three decades.

In 2004, Del Rio himself participated in the discovery and cataloguing of ‘The Woman of Naharon’, who died around the same time, or perhaps earlier, than Naia.

“I don’t know what could be more important than this, right?” said Del Rio. “We are talking about the oldest remains on the continent.”

The 1,500-kilometre Maya Train line will run in a rough loop around the Yucatan peninsula, connecting beach resorts and archaeological sites.

The government’s National Institute of Anthropology and History is tasked with protecting relics along the route but its experts largely are not able to take the deep, long, extended dives needed to reach the flooded caves.

Even near the surface, where most of the government’s archaeological work has been done, there have been stunning discoveries along the proposed path of the train.

Government archaeologist Manuel Perez has acknowledged that an almost fully preserved small Mayan temple – complete with wood roofing – has been located in a cave near the train’s path. He has suggested the route be changed.

But his boss, Diego Prieto, appeared to rule out changing the path of the train, for which workers have already cut down a 50-metre wide swath of jungle dozens of miles long. He suggested most of the relics, in the few months left before the train is built, can simply be picked up and moved.

“The problem isn’t the route … even if the route is changed, there are going to be lots of discoveries anyway,” said Prieto. “The problem is the archaeological work to gather the material found, and conserve those structures that should remain on site.”

The caves along the coast were probably dry 13,000 years ago, during the last ice age, and so once sea levels rose at the end of the ice age and they flooded, they acted as time capsules – very fragile ones. The government’s plan is to sink beams and cement columns through the roofs of the caves, probably collapsing them – and the invaluable relics they hold – to support the railway.

That’s not to mention the 68-kilometre swath of jungle that is being cut down to make way for this segment of the train line, in addition to the tonnes of crushed rocked that will have to be piled atop the soil to create a bed for the 160-kilometre-per-hour train.

Caribbean coast diver and environmentalist Urbina Bravo said “making decisions without the support of science, without the backing of specialists has cost us very dearly” in projects around the world.

“We continue and will continue to pay the price for these errors.”

But López Obrador dismisses critics like Del Rio and Urbina as “pseudo-environmentalists” acting on behalf of business interests or political opponents. The president attacks experts, activists and anyone who questions his sudden and unplanned decision to run the railway line through the jungle, which he dismissively called “acahual” (roughly, ‘second-growth forest’).

Government tourism agency building the train line spokesman Fernando Vázquez said, “There are people who in essence are not necessarily working in favour of the environment, but rather are specifically activists against the Maya Train.”

Activists said theirs is a labour of love.

To find The Woman of Naharon remains, divers had to snake through almost a half-kilometre of utterly dark, sinuous caverns; the process took months.

But the government archaeologist who is responsible for ensuring the train won’t damage such artefacts, Helena Barba, told local media her team will catalogue all the dozens of sites in the few weeks or months before the heavy machinery rolls in.

That strikes divers and cave explorers as preposterous.

“Quite possibly none of them have the experience or technical preparations to do this kind of dive in the most extensive flooded caves in the world,” Del Rio said.

So obsessed is López Obrador with his pet projects – a huge oil refinery on the Gulf coast, a rail link between the Gulf and a seaport on the Pacific, and the Maya Train – that he issued a decree stating that priority government projects no longer needed environmental impact statements, or EIS, to start work; they could start construction, cut down trees and excavate, and submit an EIS later to justify damage already done.

Urbina and environmentalists and divers challenged that in court, winning an injunction that stopped the jungle rail line between the resorts Cancun and Tulum in mid-May.

Authorities tried to overcome that problem by submitting a hastily-drafted EIS on May 19.

Mexico’s Environment Department approved the impact statement just one month later.

The EIS treats the cave systems largely as a construction problem, in the few paragraphs in which it even discusses them.

If construction crews come across caves and sinkhole lakes known as cenotes in the train’s path, they will “be able to mitigate” the damages, according to the impact statement.

What that means in plain language is already visible along the highway between Cancun and Tulum where the rail line was originally projected to run as an elevated rail line.

López Obrador changed the plan after stripping trees and laying foundations for the elevated line, purportedly when hotel owners and residents along the coast complained the construction work would affect tourism and their properties. (In fact, the government never explained why the route was suddenly changed or how much the change cost.)

To repair the collapsed cave roof on the highway, tourism agency spokesman Vázquez said the government used a quick and intrusive fix.

Urbina said the decision to invoke national security powers was “a violation of the law that we fear could do irreversible damage to the jungle”.