(ANN/CHINA DAILY) – In the heart of Jiangxi province lies Jingdezhen, China’s porcelain capital, a city steeped in tradition yet embracing modern innovation.

Jingdezhen’s allure lies not only in its history but also in its ability to evolve with the times. Some artisans have reimagined porcelain forms, blending tradition with modern aesthetics to appeal to contemporary tastes.

Others have fused porcelain with oil and watercolour painting techniques, creating unique and captivating works of art.

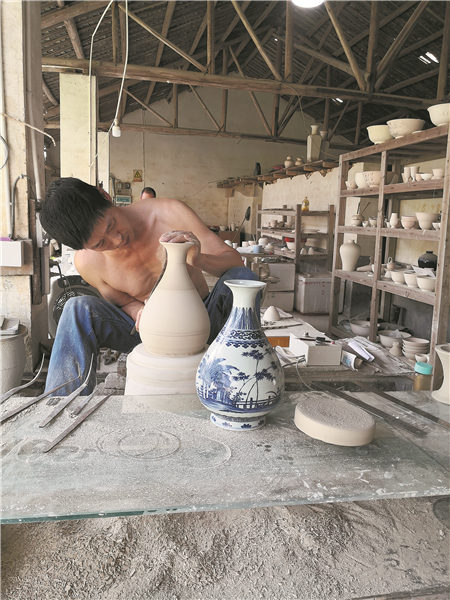

Despite technological advancements that have streamlined production, there are craftsmen in Jingdezhen who remain steadfast in their dedication to traditional methods.

They see themselves as custodians of a rich heritage, striving to maintain the warmth and charm of ancient porcelain-making in a rapidly changing world.

Over the years, this historic city has become a magnet for potters and artists from around the globe, each leaving their mark on its rich tapestry.

One such artist is Gong Hua, a master of porcelain-making in his 60s. In 2003, Gong embarked on a remarkable project: building a wood-fired kiln following Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) designs.

“It is elliptical and about four or five meters deep and 1.8 metres at the widest, much smaller than modern kilns,” he explains.

Despite the kiln’s obvious drawbacks, such as the materials used in its construction not being as resistant to high temperatures as modern ones, it honors the production techniques and materials of Jingdezhen porcelain from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) onward.

Gong’s kiln has been used to create duplicates of porcelain artefacts for many museums and collectors, to protect the originals.

“Much has been written and recorded about traditional porcelain craftsmanship, but turning the raw materials into physical objects is a cumbersome and laborious process,” Gong says.

“From the preparation of the materials, the shaping of the porcelain body and painting, to firing in the kiln, every step requires repeated experimentation.”

Born and raised in Jingdezhen, Gong grew up with piles of porcelain shards stacked beside old houses. “People casually picked them up, laughing as they threw them into the river to see if they would float. The shards created ripples in the water, and ripples of laughter,” he recalls.

This early exposure predisposed him toward porcelain making, and he became involved in its design after finishing art studies at Jingdezhen University in 1984.

As Gong immersed himself in the world of ceramics, his interest in historical porcelain intensified and he frequently wondered how he could recapture the beauty of ancient porcelain.

In 1987, during the urban renewal of Jingdezhen, Gong saw porcelain shards being unearthed at archaeological excavations.

They exposed him to the vast gap between modern ceramic craftsmanship and that of ancient times. “The glaze was as smooth as jade, and their beauty was indescribable,” he says.

This set him off on a search for paints, materials and other elements to match historical standards.

More than 1,000 years of porcelain making has left Jingdezhen a rich legacy, which provided Gong with an insight into ancient procedures.

“I was able to find treasures in local households,” he says.

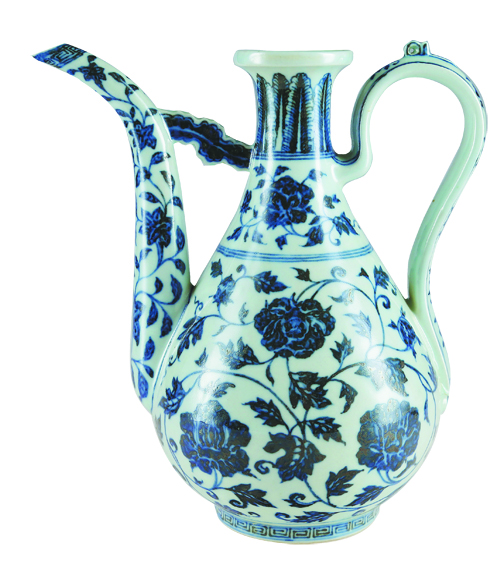

In the early 1990s, he spent three years researching and deciphering the craftsmanship of blue-and-white porcelain made during the Ming Emperor Xuande’s reign (1426-35).

“I found that the blue and white colours were thanks to the rich trace metal elements in their raw materials, which came from the Middle East and differed greatly from those sourced domestically,” Gong says.

In terms of painting techniques, porcelain ware from the Ming Dynasty is mostly characterized by a free and easy expression, while that of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) is known for its more clear-cut strokes.

He then had to rediscover the ancient firing methods, which required repeated experimentation to discover the optimal temperature and the right mix of glaze materials to deliver a porcelain surface akin to jade.

By the end of the 1990s, he also managed to recover the porcelain-making process used during the reign of Emperor Chenghua (1465-87) of the Ming Dynasty.

Since then, Gong has studied hundreds of items of blue-and-white porcelain from ancient imperial kilns, which has allowed him to fully explore and research the evolution of their craftsmanship.

“During the Han (206 BC-AD 220) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, the original glaze used on Jingdezhen ceramics was prepared from rice straw ash that had been fermented. Its high iron content explains the brown colour,” Gong explains, adding that ancient people explored the use of local plant materials and eventually settled on ferns, which grow abundantly in the mountains and fields around Jingdezhen.

“As a result, clear and elegant blue-and-white porcelain was born,” he says, adding that this plant material is the key to achieving the lustrous jade-like glaze and is ruined by modern electric and gas kiln equipment.

“Although they are hard to control precisely, only traditional wood-fired kilns can process the porcelain in an extraordinary way that may go beyond your imagination,” he says.

Gong also found that the formula for the clay went from using only porcelain stone, which can’t withstand temperatures in excess of 1,200 C, during the Song Dynasty, to adding kaolinite during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to achieve a higher firing heat.

In 2008, Gong was entrusted by the Beijing Cultural Heritage Bureau with replicating a dozen Ming and Qing porcelain items.

Gong and his team studied vital clues from previous eras.

“Every tiny part might hide important information and can’t be overlooked,” he says.

He could even gauge the psychological state of the ancient craftsmen during the crafting process.

“The way they felt affected their breathing, which can have an effect on the stability of each line being painted,” he explains.

In 2008, Gong donated the tools and traditional materials that he had gathered over the years to the Capital Museum in Beijing.

More recently, he has been working to expand traditional porcelain craft to modern users, allowing visitors to be part of the process of the traditional porcelain firing in his ancient-style kilns in Jingdezhen. “They can draw patterns on the embryos and have them fired by professional craftsmen,” Gong says.

For Gong, the modern electric and gas-powered kilns are signs of technical progress, and have a high firing success rate. “However, traditional ways should still have a place to create a balance and maintain diversity, cultural protection and inheritance,” he says.