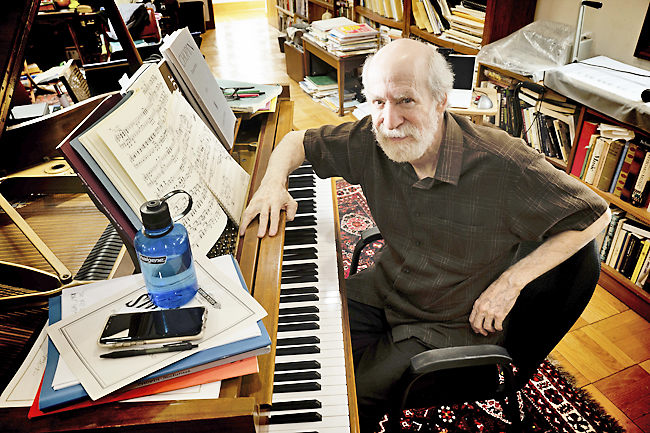

Michael Andor Brodeur

THE WASHINGTON POST – If you want to prepare yourself for the worst that can happen, learn to play the piano.

At least, this is one of my takeaways from speaking to Haskell Small, a DC-based pianist, composer and educator for whom the piano has acquired new significance. Once the anchor of his musical life, his instrument is now something more like a sail, pulling him forward through one of the stormiest passages of his life.

In February 2021, while at home with his wife, Betsy, Small was suddenly unable to stand up or move. He remembered feeling extreme stress just beforehand, he remembered Betsy calling 911 and he recalled the medics whisking him away to intensive care. Small had suffered a severe haemorrhagic stroke.

“I consider myself very lucky,” said Small, 73, in a phone conversation last week. “My mind and my speech remained intact, but at first I could hardly move my left side.”

Small spent several gruelling months in an acute rehab centre, where he re-learnt how to walk and slowly regained partial mobility in his arm and leg.

“One thing my (physical) therapist said when I saw him the first time was that one of the best therapies for recovery from a stroke is playing piano,” said Small. “Musicians and athletes have the best chance of recovering facility after a stroke, because they’ve learnt the value of practicing, of repeating over and over, of working towards a common goal and really trying to get inside the problem and exercise and use the mind. This comes down to mind over matter.”

Small’s physical therapist, Bethesda PhysioCare president and owner Jan Dommerholt, grew up playing clarinet and saxophone, which extended into his time in the Dutch military. When Dommerholt started practising physical therapy, he found himself particularly interested in the problems faced by musicians. He even keeps a piano in his office. (“It’s hard to bring your own piano to therapy sessions,” he tells me).

Dommerholt said the deeply set muscle and musical memories that musicians rely on to play can actually be a hindrance rather than an asset to their recovery.

“When part of the brain gets knocked out by a stroke, the challenge then is to activate other parts of the brain. Parts of the motor pattern may have been embedded in the part of the brain that no longer works. So part of the challenge for Haskell is to activate other parts of his brain that can take over that function. His old motor patterns are not necessarily helpful because he has no access to them. He has to create new ones.”

The imitative relationship between life and art is at the core of Small’s recovery, though in a more literal way. Dommerholt said one of the key exercises he uses is “mirror therapy”, in which patients focus on a mirror image of the functional hand while trying to move the impaired one – an exercise which essentially tricks the brain into creating new pathways.

They’ve also employed “lateralisation” therapies to reinforce the distinctions between the left and the right that Small’s brain must re-learn.

When they first started working together, Small needed to use his right arm to lift his left onto the keyboard. Dommerholt has been astonished by the rate of Small’s recovery, and expects him to return to two-handed playing within six months to a year.

Small, meanwhile, is operating on a more optimistic schedule. As both fete and fuel for his ongoing recovery, he’s planned a series of recitals built around one-handed repertoire. Titled A Celebration of Healing, a pair of Maryland recitals – at Springfield Presbyterian Church in Sykesville on April 10 and Friendship Heights Community Center in Chevy Chase on April 27 – found Small performing his own arrangements of works including Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonata in C Major (K 159, Longo 104), Schubert’s Impromptu in G-flat (Op 90, No 3), and a transcription of Bach’s Cello Suite No 6, inspired by the “tiny bit of cello” Small plays.

Small said the musical conversation within the Scarlatti piece was something he could just manage with one hand, preserving its virtuosity while necessarily excising some notes. He described the process of learning Schubert for one hand as “revelatory” for the reintroduction it gave him to the architecture of the Impromptu – a guided tour of the composer’s mind.

He also performed a new composition, Diary of a Stroke: The Adventures of Herb and Pete, titled after the pet names Small bestowed upon his left leg and hand, respectively. It bears mentioning here that the pianist’s approach to rehab owes just as much to his sense of humour as to his natural disposition toward discipline.

The 17-minute arc of Diary blooms from an angular, heavily pedalled, seven-note figure that seems to be trying to remember itself. It searches and branches out, occasionally distracting with a nostalgic melody that passes like the outline of an unrelated memory. Small said he was trying to re-create the mood and fatigue that immediately followed the stroke. Indeed, its shape feels neural.