Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – Nearly all readers keep a mental bucket list of books that seemingly everyone in the world loves, but that they themselves – secretly hanging heads in shame – have never quite gotten round to. I, for instance, am exceptionally, perhaps egregiously, fond of both canonical and genre classics, but until last week, I’d never even opened Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s 1925 masterpiece.

In fact, I’d never read any of Woolf’s fiction whatsoever. From various surveys of 20th-Century literature, I knew that Woolf’s books, notably Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse and The Waves, were lyrically written and intensely concerned with the delineation of character.

The general facts of her life I also knew from having enjoyed works by and about her gossipy Bloomsbury friends Lytton Strachey, Desmond MacCarthy and David Garnett, among others.

Yet even though I occasionally dipped into her many essay collections, the fiction remained terra incognita. I once tried Orlando and gave up after a dozen pages. It just didn’t catch fire for me.

But a few days ago, I picked up an old Modern Library edition of Mrs Dalloway and, as I should have known, discovered a marvel. As they say, better to have arrived late for the party – that’s an in-joke for those familiar with the novel – than never to have gone at all.

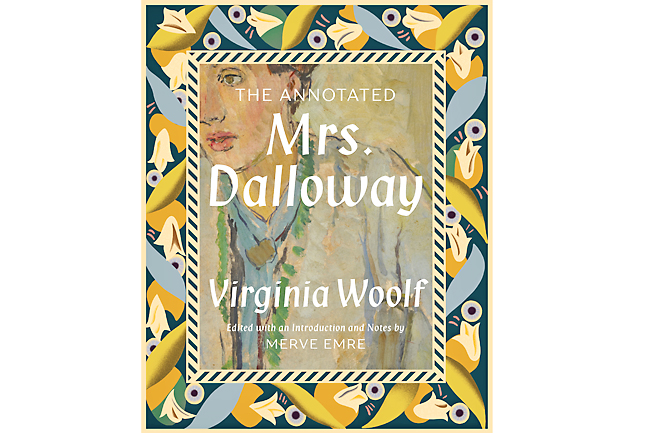

I’d finally broken the ice because I wanted to review Merve Emre’s just-published The Annotated Mrs Dalloway, and it seemed sensible to first approach Woolf’s book straight on rather than as a beflowered monument.

Like similar volumes, The Annotated Mrs Dalloway provides a scholarly and biographical introduction, lots of illustrations and extensive marginal notes that explain obscurities, identify people and places, and provide interpretive comment. Emre, however, isn’t critically neutral; she draws mainly on the work of her teachers and contemporaries, while pretty much ignoring older Woolf scholarship.

More surprisingly, there’s no appendix reprinting the seed story, Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street,” or the introduction Woolf contributed to my 1928 Modern Library hardcover. Emre prefers a relatively lean but elegant annotated edition, resolutely focussed on explicating the work’s meaning and mysteries.

“Mrs Dalloway’” she begins, “traces a single summer day in the lives of two people whose paths never cross: Clarissa Dalloway, just over 50, elegant, charming, and self-possessed, the wife of Richard Dalloway, a Conservative member of Parliament; and Septimus Warren Smith, a solitary ex-soldier, a prophetic man haunted by visions he cannot explain to his anguished wife Lucrezia.” Emre then quickly sketches the minimal plot, which climaxes with the chic dinner party at which Mrs Dalloway learns of Smith’s suicide.

Throughout, the novel satirises the English upper classes as shallow and superannuated, vividly evokes the post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the bloodbath that was World War I, reminisces about an Edenic past of rose gardens and golden afternoons, and probes, from multiple points of view, the enigmatic essence of Clarissa Dalloway.

Woolf organises the action around certain symbolic objects and events – an expensive automobile backfiring, a skywriting airplane, the crowded shopping streets of fashionable London, the Dalloway party – and effortlessly segues from one character’s consciousness to another in a series of subtly interconnected interior monologues.

As befits an Oxford professor, Emre’s commentary on all this is both learned and lucidly expressed. She neatly points out, for example, the parallels between an author structuring a book and a hostess planning a successful party.

Still, Woolf’s characters remain problematic and endlessly tantalising. Emre sees Mrs Dalloway and Septimus as soul mates, celebrating and embracing life, albeit in differing ways: “He kills himself,” she stresses, “not because life is unbearable, but because it is good and he does not want it to be otherwise.”

Yet how are we to judge Clarissa’s former suitor Peter Walsh, her devil-may-care friend Sally Seton, and all the others from her present and past, many of whom reassemble at her party? Woolf, in Emre’s view, wants us to regard most of them as failed human beings, egotists and supporters of a social order based on lies and facade.

No doubt she’s right. And yet I find this judgement harsh, for I can’t help but admire their stoicism and the orderly world they served and believed in. Richard Dalloway may be a bit stiff, but he deeply loves and provides for his wife and their adolescent daughter.