Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – Last month, when Vladimir Putin was still massing troops on the Ukrainian border, I decided to read Seven Pillars of Wisdom, TE Lawrence’s memoir of the 1916-1918 Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

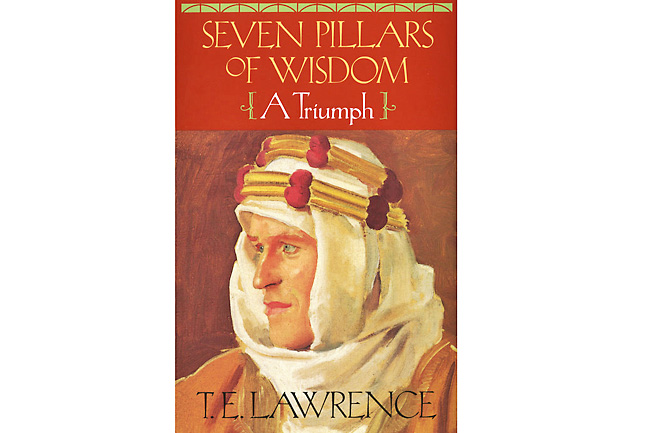

The “private” edition first appeared 100 years ago in 1922, by which time its author had already tired of being called Lawrence of Arabia. Still, this account of how a young Englishman helped lead a Bedouin guerrilla force tasked with blowing up trains and rail lines is subtitled ‘A Triumph’. I wanted the same outcome for Ukraine, birthplace of one of my wife’s grandfathers, in its struggle with Russia, birthplace of one of mine.

If you’ve seen David Lean’s breathtaking film Lawrence of Arabia, you already know the overall arc of the narrative. During World War I, the Ottoman Empire allied itself with Germany, which led Great Britain to send troops to the Middle East.

At roughly the same time, Sharif Hussein ibn Ali inaugurated an independence movement to break free of Turkish domination. Because Lawrence had spent time on archaeological digs and could speak Arabic, he was commissioned as a liaison between the British army and the ragtag rebel forces. Surprisingly, the young Oxford graduate, not yet 30, first earned the trust of Feisal, then persuaded the Bedouins to adopt hit-and-run battle tactics.

Highly mobile fighters on camelback, he argued, could strike the enemy unexpectedly, then quickly disappear into the desert they knew so well. Soon nicknamed ‘Prince Dynamite’, Lawrence showed himself to be – in the words of military historian BH Liddell Hart – “a supreme artist of war”.

Five feet five inches tall, he was also an excellent gymnast, a crack shot and a skilled mechanic. During the revolt, Lawrence carried Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur in his saddlebag and in later life translated Homer’s Odyssey. Abstemious about food and drink, Lawrence was utterly uninterested in acquiring possessions or wealth, while many have testified to his spiritual charisma and intensity. He repudiated the least suggestion that one race was better than another.

As a writer, Lawrence excels at portraiture, topographical description, confession and the depiction of combat. Auda, the fiercest of all Bedouin warriors, “had married twenty-eight times” and “been wounded thirteen times; while the battles he provoked had seen all his tribesmen hurt and most of his relations killed. He himself had slain seventy-five men with his own hand in battle: and never a man except in battle. Of the number of dead Turks he could give no account: they did not enter the register”.

Lawrence’s evocations of landscape range from the sharp and swift – “The heat of Arabia came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless” – to the intensely tactile, as when the rebel forces trek through the Wadi Hamdh river, “a trough 15 miles across”. The sand was “rotten with salty mud and flaking away, so that our camels sank in, fetlock deep, with a crunching noise like breaking pastry. The dust rose up in thick clouds, thickened yet more by the sunlight held in them; for the dead air of the hollow was a-dazzle”.

For many readers, the most horrific episode in a work replete with shocks occurs when his forces enter the massacred village of Tafas. After coming upon sickening atrocity after atrocity, the Arabs discover “a three or four year old child, with a huge wound where neck and body joined. She tottered forward and cried ‘Don’t hit me, Baba’. Abd el Aziz, whose village this was, stumbled toward her, she screamed, then died”.

Overcome with anguish, one of Lawrence’s best fighters madly gallops into the midst of the fleeing enemy soldiers and is immediately cut down. At that point, Lawrence finally gives his command, “I said, ‘The best of you brings me the most Turkish dead’. “For the only time, he added, “by my order we took no prisoners”.

At first, the long-sought capture of Damascus might seem to be the climax of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Yet the book’s actual conclusion occurs afterward, when the weary-hearted Lawrence, urged to visit that city’s hospital, surveys the hundreds of wounded and dying laid out on pallets. Here is the true face of battle.

Today’s readers, used to the twittering demotic of our age, may need to adjust to this titanic prose-poem’s leisurely, mandarin style. It’s worth the effort. To HG Wells, the book was nothing less than “the finest piece of prose that has been written in the English language for 150 years” – In other words, since Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Like Gibbon’s masterpiece, Seven Pillars of Wisdom can be criticised as slanted, partial and even unreliable. But as epic and psychological document, it remains a stunning achievement.

It’s also something of an encyclopedia, providing reflections on Middle Eastern history, the nature and appeal of fanatical piety, the sociology of Bedouin life and, sadly, the Western Allies’s political duplicity.

While this great book’s monumentality can certainly be daunting, reading it is an experience you will never forget.