Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – In What Is Literature? Jean-Paul Sartre emphasised that authors shouldn’t think about posterity but rather write for their own time.

This has always struck me as an obvious precept, even when poets and novelists can’t help but hope that somehow their best work might become, as Horace boasted of his odes, a monument more lasting than bronze.

At least journalists know that that’s never going to happen.

Ephemerality, however, simply makes it more urgent to read 2022’s best books right now: After all, they address the hopes and dreams, the anxieties and fears of this moment. They will also deliver considerable pleasure, add to your understanding and – to sound a bit corny – enrich your inner self. Not least, you will have done your part to keep literature, critical inquiry and scholarship vital and flourishing in what sometimes seems a barbaric age.

Knowing all this, I nonetheless want to make the case for reading old books.

When I was young, I didn’t yearn to be rich, successful or famous but instead desperately wanted to feel at least halfway educated. To me, that meant gaining familiarity with history, art, music, languages, other cultures and the world’s literature. The foundations of learning, I quickly realised, were nearly all located in the past. Time had done its winnowing, and what remained were the works and ideas that shaped human civilisation.

In many instances, the past also provided the templates, inspiration or provocations for later achievements in the sciences and the humanities.

Old books, after all, help create new ones. Zadie Smith’s On Beauty pays homage to EM Forster’s Howards End, and Barbara Kingsolver’s recent Demon Copperhead updates Dickens’ David Copperfield. Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire supplied Isaac Asimov with the secret armature for science fiction’s Foundation trilogy.

In the arts, especially, education consists of seeing how deeply the past informs the present. Knowing what earlier generations accomplished conveys perspective, the capacity to recognise the new from the retrograde, the original from the pastiche. In literature, the popularity of “annotated editions” of various classics shows how much we still value basic contextual information about earlier historical periods – and, paradoxically, how much we have forgotten of what was once traditional cultural literacy.

The great books are great because they speak to us, generation after generation. They are things of beauty, joys forever – most of the time. Of course, some old books will make you angry at the prejudices they take for granted and occasionally endorse. No matter. Read them anyway. Recognising bigotry and racism doesn’t mean you condone them. What matters is acquiring knowledge, broadening mental horizons, viewing the world through eyes other than your own.

Does that mean you should devote your evenings to arguing with Plato, working your way through Dante and learning how to live from Montaigne? Being an idealist, I think you should, though certain classics – Samuel Johnson’s moral essays, George Eliot’s Middlemarch – are best appreciated in middle age, when they will pierce you to the marrow.

Still, literature’s Himalayan peaks can be daunting. As the Victorian classicist Benjamin Jowett once said, “We have sought truth, and sometimes perhaps found it. But have we had any fun?” In reading as in life, fun does matter.

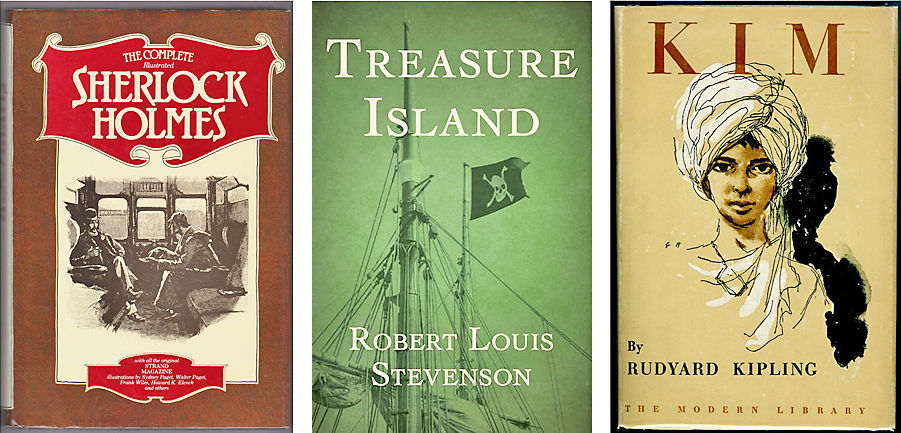

For several years now, I’ve been exploring popular fiction published in Britain between 1880 and 1930. I started doing this because of my fondness for Arthur Conan Doyle’s books and my subsequent discovery that the creator of Sherlock Holmes flourished in an age of wonderfully entertaining novels and stories.

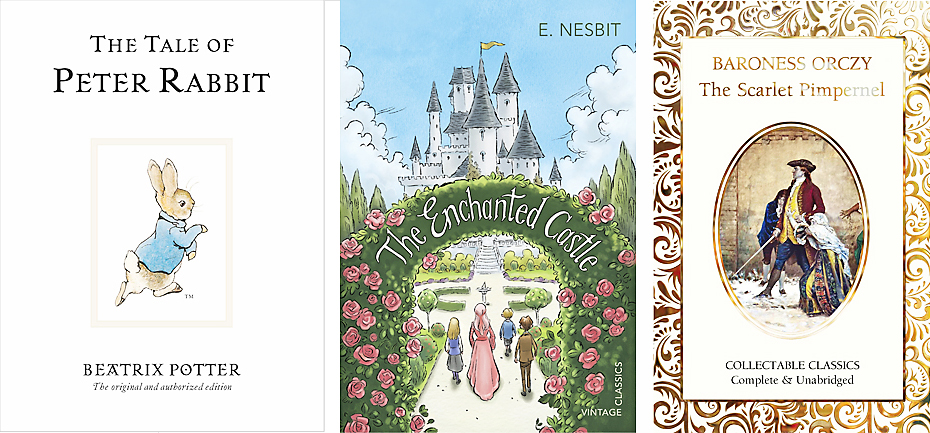

Imagine how poor our imaginative lives would be without Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, H Rider Haggard’s She and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, without Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, E Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle and Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel without John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood and PC Wren’s Beau Geste.

For that matter, have there ever been better ghost stories than those of Vernon Lee, MR James and EF Benson? And are any later Napoleons of Crime more nefarious than such rivals of Professor Moriarty as Guy Boothby’s Dr Nikola and Sax Rohmer’s insidious Dr Fu-Manchu or, a personal favourite, the urbane Monsieur Zenith, the albino mastermind of the Sexton Blake thrillers? As for female criminal geniuses, they don’t come more accomplished, deadly or heartless than Madame Koluchy and Madame Sara, who appear in, respectively, The Brotherhood of the Seven Kings and The Sorceress of the Strand, both by LT Meade and Robert Eustace.

Some of these titles will be familiar, largely because of movies based on their plots.

Others probably aren’t, which is a pity. Too few people now read Walter de la Mare’s subtle, sui generis masterpiece, Memoirs of a Midget, or Grant Allen’s tales of a roguishly likable con man collected in An African Millionaire. Even though I revere PG Wodehouse’s every sentence, my very favourite comic novels are Jerome K Jerome’s high-spirited Three Men in a Boat.

Today, most of these works are in the public domain and readily available from Project Gutenberg, the Internet Archive or in cheap reprints. I discovered many of them simply by asking friends about what books they loved. That’s how I learned about Georgette Heyer’s

historical romances.

Titles I didn’t already recognise I looked for online or when I visited a bookshop. For the various genres I’m interested in, such as the ghost story and the detective novel, I long ago bought standard critical histories, then studied them closely, especially their bibliographies. Author websites and online fan groups are obviously worth checking out, while specialist publishers frequently reissue the neglected masterworks of their respective fields.

You certainly can’t go wrong in trying almost any Penguin Classic or Oxford World’s Classic. Anthologies are also immensely useful: For instance, Dorothy L Sayer’s 1929 Omnibus of Crime and its two sequels are packed with stunning but often little-known mini-classics of horror and detection.

Obviously, too, if you like one story by an author, you’ll probably enjoy others. Having shivered over the eerie adventures of Algernon Blackwood’s psychic investigator, John Silence, I was led to other mysteries featuring occult detectives, starting with William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki the Ghost-Finder and Dion Fortune’s Dr Taverner.

As inveterate readers know, the most surprising old books regularly turn up at yard sales and thrift stores or in those Little Library boxes. Big libraries, too, are always worth visiting, whether to ask for suggestions from the librarian or to simply prowl among the shelves.

When at loose ends, I like nothing better than to spend an hour or two wandering around a used-book shop, picking up titles that seem promising, then skimming a few pages. This is a particularly good practice with volumes of poetry. For example, Ernest Dowson might seem a minor figure of the 1890s, but he wrote the unforgettable line “I have been faithful to thee, Cynara, in my fashion” as well as phrases everyone knows: “gone with the wind”.

All of us should strive – as Sartre advises – to engage with the books of our own time. At the very least, albeit sometimes wearyingly so, they remind us of how much in our world needs fixing. After all, it’s hard to fault Marx’s activist observation that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it”. Yet the books of the past, besides adding to our understanding, offer something we also need: repose, refreshment and renewal.

They help us keep going through dark times, they lift our spirits, they comfort us. Which means that I also strongly agree with the poet John Ashbery, who once wrote, “I am aware of the pejorative associations of the word ‘escapist’, but I insist that we need all the escapism we can get and even that isn’t going to be enough.”

So, go ahead and pick up a few appealing titles, but don’t forget that there are other, older books worth reading, especially when the world is too much with you. As the weather grows colder, it is, for instance, a perfect time to settle in with Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, Saki’s ironic short stories or Anita Loos’ immortal Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.