Joyce Yang

CNA – It’s 2023 and buying spectacles has never been this easy. You can pop by any optical shop in the mall and help yourselves to shelves upon shelves of frames. A new pair of prescription glasses can be ready in as little as 20 minutes.

This makes Lim Kay Khee Optical House an anomaly. Located along Balestier Road, the establishment concerns itself with neither self-service racks nor designer brands.

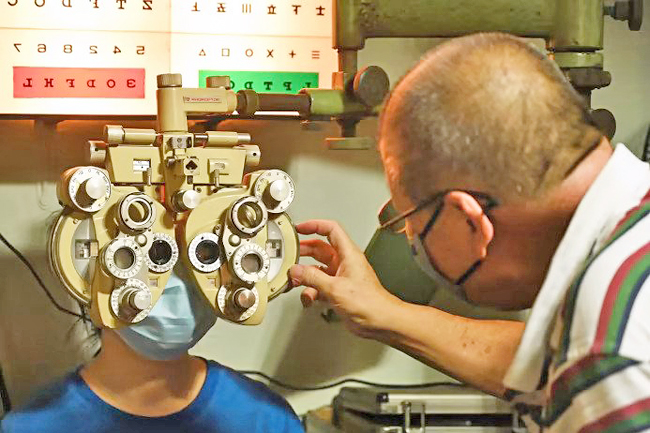

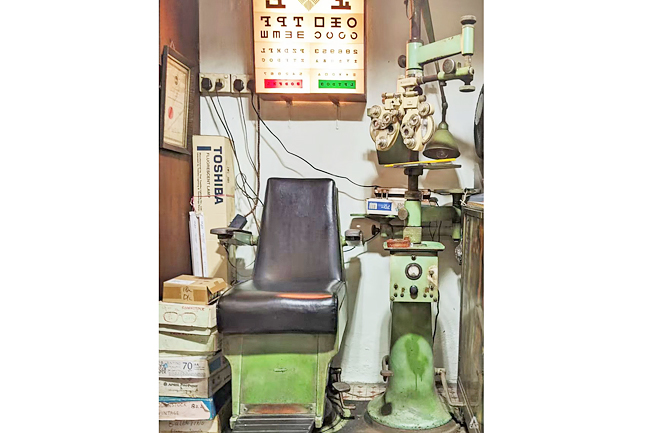

In their place are patterned floor tiles and machinery preserved from the 1960s, as well as a palpable lack of air-conditioning.

“The other stores in Hougang and Peninsula Plaza look modern, unlike our ulu (Malay for “remote”) shop here,” said owner Lim Seah Seng, 67.

While his elder brothers run the family business from its newer branches, he and his sister, Karen Lim, are heirs to the flagship.

But why does the storefront say “Great China Trading Co”?

WARTIME WHOLESALER TO OPTICAL SHOP

“When the Japanese occupation started, a French salesman who fled Singapore left my father with a box of catalogues.

“They had contacts of suppliers overseas, so he used it to become a wholesaler,” Karen Lim said.

That was how Great China Trading Co started selling everything under the sun, from pencils to compasses and magnifying glasses.

The late Lim Kay Khee never set out to be an optician, but his affinity with the trade emerged in a crisis.

“During the war, the Japanese nabbed a man to fix their soldiers’ glasses. But that man couldn’t do it and referred my father to escape execution. They were satisfied with my father’s work, and rewarded him with food coupons,” she explained.

One thing led to another, and her father pivoted to the eyewear business altogether in 1946.

In the olden days, the shop came through for short-sighted children who could not afford spectacles.

Students could exchange a letter from the school for a pair of prescription glasses – no questions asked. “We still offer special discounts to the underprivileged, but I think many have forgotten about it.”

WHERE OPTOMETRY MEETS ARTISTRY

Lim dipped his toes into the trade once he turned six. He swept floors, polished frames, and joined his brother on deliveries, making it to school at Balestier Hill just in time at noon. He watched his father work 12-hour shifts, drawing the shutters only for three days a year.

A great many weeknights of his childhood were spent watching customers come and go until his eyelids grew heavy, but hard work didn’t keep him away.

“I took an interest in reshaping spectacle frames, and slowly picked it up from my mother,” Lim said. In his nimble hands, a pair of oval frames can shape-shift to become rectangular, round, or square.

Proudly, he informed me that this service is exclusive to the Balestier shop. Out of six children, only he has complete mastery of the craft. “I spent at least three to four years perfecting it. Your hands have to be extremely stable. Your measurements have to be marked precisely.

“Otherwise, the rims won’t be even. It may look okay to you, but I can tell it isn’t.”

He shoved a pair of asymmetrical sunglasses in my direction – one rim was round and the other was triangular. After seeing someone rock it at the National Day Parade, Lim recreated it. “Looks funny, right? Even ordinary folks can turn heads on the street when they wear these.”

Tour guides and musicians fancied these designs, which took at least half an hour to customise. Even though well-meaning friends urged Lim to charge a premium for his craft, their words fell on deaf ears. “Can sell okay lah,” he quipped.

Importantly, tweaking an original model in five or six ways gave customers more styles to choose from, helping inventory to move more quickly.

However, the reshaping of spectacle frames has since been automated. Lim’s artistry makes an appearance only when there’s a technical fault or urgent request.

But that isn’t the only lost art here. The optical shop used to dye sunglasses manually, too.

Customers would choose from over 30 lens colour samples, and Lim would deliver in two days. However, he feels no nostalgia for the painstaking process.

“It wasn’t lucrative. Sometimes, you can’t get the right shade, and you have to start over.

“I warned customers that if they want it quickly, it will not be perfect. We can probably meet 85 per cent of their expectations.”

Nailing his customers’ requests, especially for gradient glasses, was a back-breaking task involving toxic chemicals. Naturally, it is now outsourced to laboratories.

LONGTIME REGULARS AND STAR APPEARANCES

Until the late 2000s, spectacle frames sat in crowded display cases, retrieved by opticians only when something catches our eye.

These days, open-concept stores offer a far more autonomous experience. Customers, even those with perfect eyesight, can try on a dizzying variety without speaking a word to the optician. It’s an introvert’s dream come true.

For the same reason, some patrons feel uneasy when Lim tries to assist them. Meanwhile, others appreciate his service and recommendations – the whole nine yards.

Selecting a pair of spectacle frames with no expertise can be dicey, he said. For example, semi-rimless glasses may not suit highly myopic customers.

Because lens thickness increases with prescription, the lens may end up looking disproportionate to the frame. “Most shops out there will not tell you. They would rather not because you will have second thoughts. With my customers, I usually overstate the expected thickness so I have some buffer to work with. If I can achieve a thinner lens, I’m happy and they’re happy.”

Customers were won over by his work ethic and among the shop’s regulars is an 80-year-old who had practically watched the siblings grow up. Occasionally, elderly customers would request retro designs from their youth. Using their old photographs for reference, Lim can easily recreate them.

The shop attracts a young crowd, too. Some of them are children and grandchildren of his loyal fanbase, whom Lim affectionately calls “our supporters”.

“When one of them brought his daughter here, she complained. So old! Why did you bring me here? I said never mind, you can take a look and try the air-conditioned stores in the city. Those are classier but she still ended up here,” he beamed.

Lim’s wide selection of designs remains a draw, which explains why he would rather invest in the shop’s variety than its appearance. Besides, customers have made their case against modernisation.

“Some of them say: Uncle, please don’t renovate the shop. It’s a headache for me. If I renovate it, it’ll cost money. If I don’t, it looks dowdy. To each his own. Some customers like the nostalgic look but others find it cluttered.”

The good old days linger in the shophouse, which has attracted a handful of filmmakers and stars alike. Yet, when boy band 5566 dropped by in the early 2000s, Lim attended to them as he would most walk-ins.

“We didn’t know who they were until passers-by cried out: That’s 5566! A crowd formed and some of them were huge fans. We didn’t even know they were celebrities. We just served them as per normal, but gave them a small discount. We didn’t take photographs with them either. Silly us!”

Lim said they were equally clueless when another mandopop icon, Kit Chan, dropped by with local artiste Bryan Wong. Apparently, veteran actors Chen Shucheng and Chen Hanwei were also customers of his. Lim recounted these encounters fondly, saying the celebrities never fussed about anything in his timeworn shop. “We have met many different types of customers. I can’t possibly talk about all of them.”

DON’T START AN OPTICAL SHOP

In the 1960s, a pair of glasses cost as little as SGD8. Balestier Road had only two lanes, and children played marbles on the five-foot way.

Pasar malams lined the street every Monday, and footfall was never a question for the optical shop.

Then came the 70s and 80s, when the authorities tightened restrictions on the industry’s qualifications. Fewer certifications were recognised, and opticians had to dig deep into their pockets to get licenced once more.

While Lim’s shop tided through the ensuing exodus, it wasn’t spared from the rise of LASIK surgery and competitors in the millennium. In the background, the Balestier neighbourhood was also transforming.

“In the past, there was a cinema nearby so we had more customers.

“It has been under renovation for the last two to three years, so business has been poor.

It’s hard to keep going,” said Lim. The only reason why they’re surviving? They don’t have to pay rent.

“My father said: You can do whatever you want with the shop. Just don’t sell the space and you’ll be able to feed yourselves.”

Since its heyday, the shop has lost nearly 80 per cent in revenue. His late father’s words never rang truer: “You won’t starve to death if you have this optical shop. But if you want to strike it rich, look elsewhere”.

For Lim, the past six decades have become a cautionary tale for wide-eyed juniors who dream of starting an optical business

“I asked them, have you thought about the holidays or the weekends? Now, you work five days a week and knock off at 5pm. That is not possible here. Don’t start an optical shop. If you want, I’ll lease mine to you and you can start anytime.”