Sophia Nguyen

THE WASHINGTON POST – Analysing other people’s relationships – which is to say, gossiping about them – can be “the beginning of moral inquiry”, wrote the literary critic Phyllis Rose. It’s how we workshop our ideas about power, care and the way we want to live.

Lately we’ve been gossip-deprived: The air’s been thick with judgement, but that judgement has concentrated in less-intimate quadrants (public health, politics). We’re hungry for stories of others’ domestic arrangements, if only to gain a little perspective on, or escape from, our own.

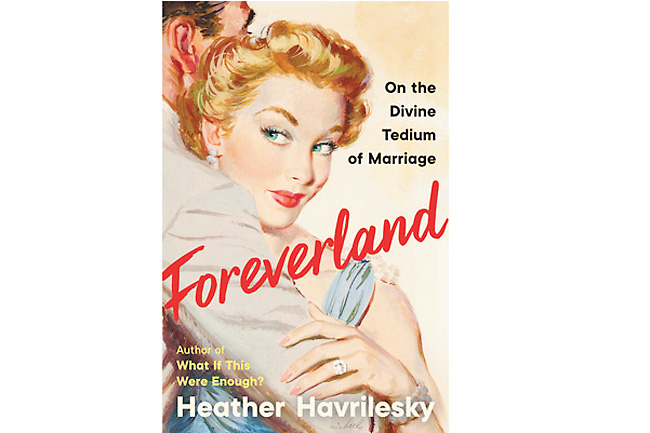

So when Heather Havrilesky declared, in the New York Times, “Do I hate my husband? Oh for sure, yes, definitely,” people took up her words with relish. The Atlantic’s David Frum likened the essay, excerpted from Havrilesky’s new book, Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage, to “filing your divorce papers in front of millions of people.”

In a now-deleted tweet, the feminist writer Andi Ziesler suggested, with magnificent passive-aggression, “It might be a net good if we stopped conflating ‘successful marriage’ and ‘marriage that lasts forever’.”

Strikingly, many readers’ responses doubled as paeans to their spouses. In a Substack post, Jill Filipovic called her own marriage “the first relationship of my life that felt expansive”.

“My marriage is a source of intense joy in my life,” Josh Barro wrote in his newsletter. “Why not shout it from the rooftops?” Albert Burneko, denouncing the excerpt as an “incomprehensibly monstrous betrayal”, also took the occasion to celebrate his wife on the website Defector: “I follow her around the house like a cat following a laser pointer.”

Some might call this defensive; I find it sort of sweet. Though their authors may not realise it, such tributes operate in basically the same genre as Havrilesky’s memoir. They at least make many of the same moves: Insist you are neither saintly nor smug for glorying in your marriage; say you got lucky.

Still, you’d be justified in taking Foreverland as an unwitting indictment of marriage, the nuclear family, the whole catastrophe. Havrilesky, the longtime author of the advice column Ask Polly, makes the milestones of white-picket-fence life sound miserable.

When they got engaged: “I knew for the first time that Bill would never stop tormenting me with his nerves and his bad judgement.” At their wedding: “I looked like an overwrapped present – hormonal, overwhelmed, underslept, jittery, full of dread.”

But for every complaint about his throat-clearing (“like the fussiest butler in the mansion”), there are some exquisitely simple moments of recognition: “Bill is my only friend,” she thinks when, at a tense moment, he puts his hand on her knee.

At some point over the years, Havrilesky explained, “my love had started to take the shape of sleepwalking”. In her view, a marriage that depends on peacekeeping through silence and studious ignorance might as well be dead; paying attention is an unalloyed, romantic good.

So is self-expression: She won’t settle for one descriptor when she can have six. The prose tumbles out in helpless run-ons, earnest asyndeton: An infant is “a cloud, a ball of white light, a sweet duckling that smells like vanilla beans, a giggling monster, an angry rabbit”.

Recounting their lives together, she overextends her metaphors so far it’s like she’s hoping to hear the joints pop.

When that verbosity swamps their fights, her husband wades in: “Thankfully, Bill is Bill,” she writes. “He boarded a boat and sailed down my river of words until we reached dry land, together.”

He listens not just with patience but also with interest. Havrilesky won’t win over everyone with her high-saturation comic style. But to readers receptive to that kind of swashbuckling bluster – Bill, I suspect, among them – the sheer effort of her prose is a kind of valentine.

Readers who crave that warm feeling of being taken into someone’s confidence will also find a lot to like in Laura Kipnis’s Love in the Time of Contagion: A Diagnosis. (Apologies to The Washington Post’s copy desk, which, not long into 2020, unofficially banned all forms of the phrase “in the time of” in pandemic-related headlines).

Like Havrilesky, Kipnis, a social critic and film professor, styles herself as a teller of unflattering truths, embracing life’s messes, completely uninhibited.

She doesn’t disclose as much about her current relationship. But her book, taking stock of the pandemic’s effects on intimacy, does go deep into her conversations with friends.

One chapter, exploring the concept of “codependency”, grows out of Zooms with a recent divorcé, Mason, in which they dissect his 20-year marriage to an alcoholic.

Another maps the dense entanglements of a former student, Zelda – “Black, and very online” – who acts as our field guide to a new lingua franca of hookups, screenshots and DMs. (Young adults, Kipnis marvels, are “creative geniuses at using their phones and screens to create unbelievable romantic chaos and misery”).

The commentary about various interpersonal dynamics never quite resolves into a particular thesis. Reading these chapters – juicy and repetitive, absorbing and exhausting – feels like looking too long at a hyperrealist painting. Objects are rendered in eye-popping detail, but our gaze has nowhere to rest.

The absence of a unifying narrative may be the point. Kipnis believes that we overvalue tidiness: The #MeToo movement primed us to view physicality with suspicion, she argued, and the pandemic only exacerbated our compulsion to police our interpersonal boundaries.

Kipnis’ best-known work may be her 2003 anti-marriage polemic, Against Love, but she shares at least this cornerstone of Havrilesky’s worldview: True intimacy is less glamorous and more laborious than anyone admits.

Decades from now, we might view Love in the Time of Contagion as, inescapably, a “pandemic book” less because of its subject matter than because of something more essential about its composition.

Its circling obsessiveness and sometimes-distorted sense of scale feel like outgrowths of this moment: a period when many of us have retreated, discouraged from making unexpected new connections, our mental habits grooved by feeds that algorithmically deliver whatever triggers us.