Mark Athitakis

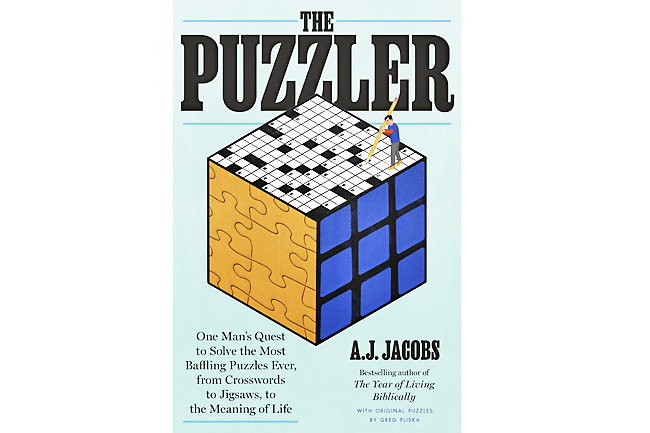

THE WASHINGTON POST – Perhaps it’s fitting that the new book by AJ Jacobs is missing a piece. For The Puzzler, he’s diligently explored the world of Rubik’s Cubes, crosswords and Sudokus. He’s logged hours in the air, recruiting his family to represent the United States (US) in Spain at the world jigsaw championship. He’s constructed and competed in scavenger hunts and talked chess with Garry Kasparov. Yet his sprightly, far-reaching book was completed too late to make much room for Wordle, the puzzle phenomenon that went viral in late 2021. Nothing has helped us find our COVID-era Zen, it seems, quite like spending a few minutes every day looking for a secret five-letter word.

Even without Wordle, there’s room for a book like this from Jacobs, who specialises in stunt titles like 2004’s The Know-It-All or 2012’s Drop Dead Healthy. The fans of games like Wordle – for which the New York Times paid a reported seven figures in January – are clearly seeking something. But what? I’m not sure myself, and I’ve long been among the seekers. I complete at least four crosswords daily, plus Spelling Bee and Wordle. Finishing a Saturday crossword in under 10 minutes gives me a ridiculously deep sense of pleasure; my ongoing haplessness at cryptics wounds my ego. The Puzzler recognises and celebrates the frustration and obsession.

But explaining that obsession is a little tougher, and though Jacobs doesn’t avoid trying, he’s mostly here to have fun. He’s mastered an avuncular, jokey, at times corny tone: Heading to Spain for the jigsaw contest, he quips that “speed-solving jigsaws sounded weird and paradoxical, like a yoga tournament or a napping derby”. And his choices in topics often spotlight the more peculiar examples in the puzzle world: the person who can finish a Rubik’s Cube in a second using his feet, the owner of a heart-crushingly difficult Vermont corn maze, and puzzlers like Jim Sanborn, the creator of Kryptos, a 1990 sculpture in a courtyard at CIA headquarters.

It contains a code that’s yet to be completely cracked. When Jacobs told a Kryptos message board he’s visiting the sculpture, the solvers have absurdly picayune requests. “Look for odd-coloured patches of grass,” one suggested.

The puzzle-world pros that Jacobs interviews have a few ideas about their fixations.

Sometimes it’s a craving for simplicity. Jacobs is particularly enchanted with that puzzling-as-self-improvement theme. “Puzzles can make us better people,” he asserted early on. Later, he argued that thinking about things in puzzle-like ways can encourage a problem-solving mind-set. “If I hear about the climate crisis, I want to curl up in a fetal position in the corner,” he wrote. “But if I’m asked about the climate puzzle, I want to try to solve it. That, to me, is the only way out of our current mess.” But that’s just semantics.

The book itself offers plenty of opportunities to do that chasing. It’s lavishly illustrated with vintage puzzles: the very first sudoku, a Soviet-era visual puzzle, a maze created by Alice in Wonderland author Lewis Carroll, a 1969 chess puzzle by Vladimir Nabokov. It’s also larded with a new batch of puzzles, created by Greg Pliska, that generally reside in the sweet spot of entertaining and frustrating that all good puzzles require.

That purse will no doubt improve the life of whoever wins it. But The Puzzler mainly shows that we make too much of puzzles as vehicles for our betterment. At heart, they just expose our funny, brilliant, quirky humanness. We love riddles, Jacobs writes, because they show how we’re “rationalisation machines. We are great at finding patterns where none exist”. And if we don’t find the pattern? That’s our humanness, too. “There’s no such thing as failure,” a chess-book author told Jacobs. “Just try to fail and fail and fail.” Mission accomplished, every day, millions of times over.