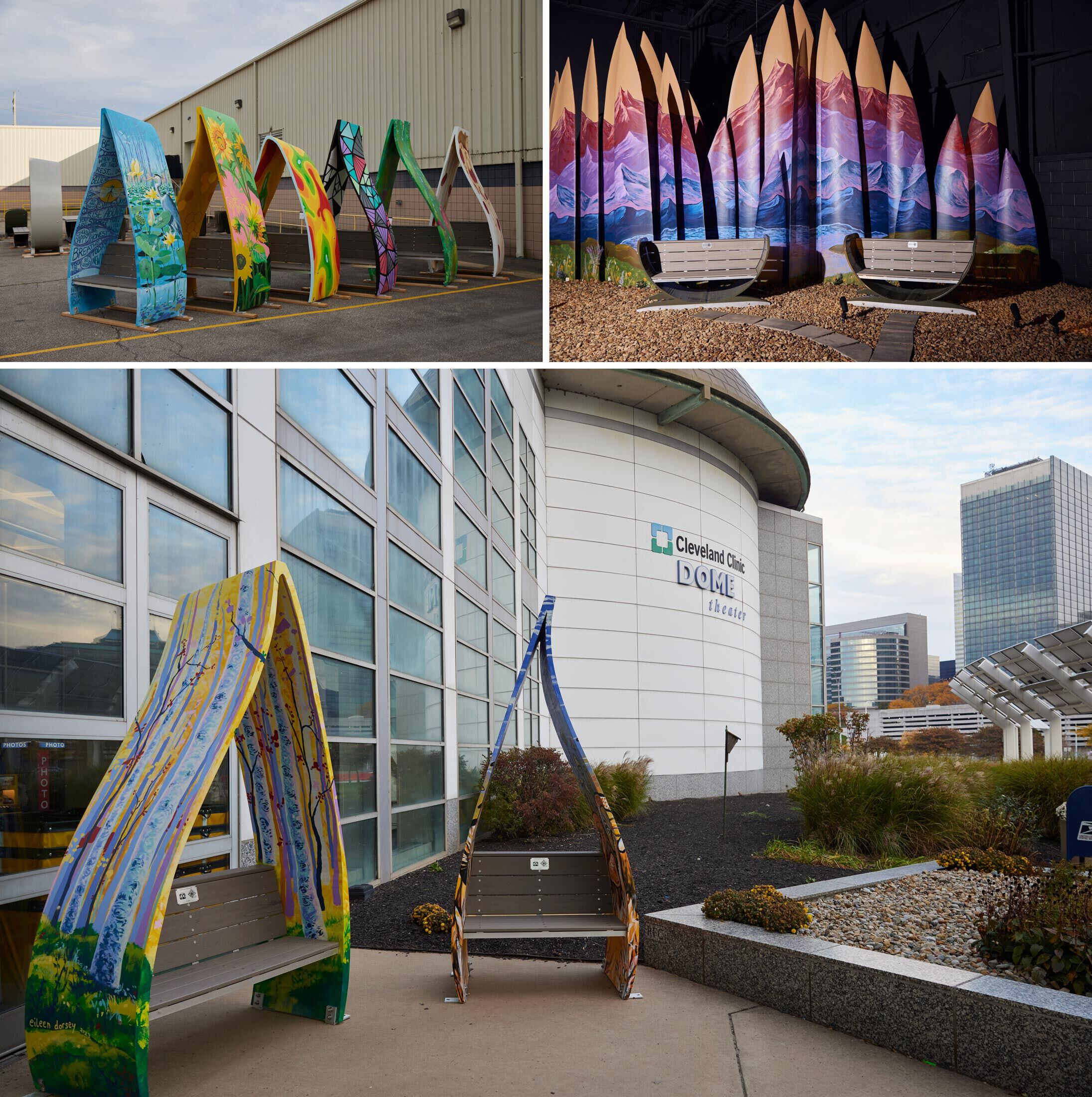

OHIO (BLOOMBERG) – At first glance, the benches outside the Great Lakes Science Centre in downtown Cleveland seem unremarkable. But a closer inspection shows that their droplet-shaped shells aren’t made from wood or metal. A scan of the attached QR codes reveals even more: These benches used to be wind turbine blades.

Painted by local artists and weighing in at about 230 kilogrammes apiece, the benches were crafted by Rocky River, Ohio-based Canvus, which will install 10 more in the same location later this month. Altogether, the dozen benches reuse roughly a quarter of a single 45-metre wind turbine blade.

“We give this material a second life,” says Parker Kowalski, co-founder and managing director at Canvus.

Many more blades will soon need second lives of their own, as wind turbines installed in the early 2000s start to reach the end of their lifespan. By 2025, trade association WindEurope estimates that 25,000 metric tons of wind turbine blades will be phased out each year in Europe alone, equivalent to the weight of more than 6,000 Hummer SUVs. Turbine manufacturers are working on making their blades recyclable, but for now startups like Canvus offer a more immediate fix: repurposing them into new products.

At the end of a wind turbine’s life cycle, roughly 85 per cent of its components – including the steel tower, copper wire and gearing – can be recycled through established metals processing. But turbine blades are a more intractable challenge. Coated with epoxy resins, they cannot easily be crushed. Blades are also made primarily from fiberglass, and lack the metals and minerals that attract recyclers.

As a result, most wind turbine blades end up in landfills or are incinerated, says Jennifer McKinley, who specializes in renewable-energy waste management at Queen’s University Belfast. That footprint only stands to grow: Total installed wind capacity reached 906 gigawatts worldwide last year, more than quadruple 2010 levels, according to the Global Wind Energy Council, an industry group. An additional 600 gigawatts are expected by 2027.

“It’s an increasingly major issue globally,” McKinley says.

To head off a looming waste crisis, turbine manufacturers are stepping up efforts to sunset their own products sustainably. In 2021, Siemens SA’s wind turbine unit unveiled a blade made from recyclable materials, and committed to producing 100 per cent recyclable turbines by 2040. Denmark’s Vestas Wind Systems, the world’s largest producer of turbines, this year developed a chemical solution that allows conventional blades to be recycled, though it has yet to be proven at scale.

But there is some risk of these efforts stalling amid wider struggles in the sector. Rising material and installation costs – coupled with locked-in contracts to sell power at low rates – are forcing wind developers to delay or even nix major projects. As the industry works out its kinks, blade-recycling initiatives could suffer.

Kowalski and his two co-founders started Canvus in 2021 after trying a different blade-waste solution: They wanted to figure out how to shred decommissioned turbine blades and use them as fuel for cement-making. Instead, they ended up deciding to lean into the hardware’s durability. “It’s long-lasting,” Kowalski says. “Why can’t we use it for a new purpose?”

The team came up with 150 ideas for products to make out of turbine blades before settling on 11 – planters, picnic tables and benches – that could be produced at scale. It also assigned each product a pithy name: the “deborah” bench, for example, offers shade protection and is also available as a swing; “beacon,” meanwhile, can be a bench, planter or fountain.

At Canvus’ 10,200-square-metre factory in Avon, Ohio, trucks arrive with pre-cut wind turbine blades from across the US; a team of 30-plus craftsmen then process the blades into smaller pieces, which are scanned to develop a 3D blueprint. The company has received more than 1,000 retired blades since 2022, Kowalski says, and has converted several hundred.

Canvus is one of a number of companies identifying new uses for wind turbine blades. Ireland-based BladeBridge has built pedestrian bridges using decommissioned blades. The Port of Aalborg in Denmark uses them as bike shelters, while Superuse Studios in the Netherlands leverages them to craft playground equipment.

But Canvus employs a somewhat unique business model: The company’s customers are mostly corporate clients, who donate the benches and planters they purchase to public spaces. Each item – prices range from roughly USD3,500 to USD9,500 – doubles as a marketing vehicle for the company that donates it. That’s because all Canvus products come with a plaque on which the donor can put their own name, as well as a QR code that loads a webpage the donor programs. Some of the products, like the beacon, also include space for brand signage.

Renting a billboard in the US would cost a company at least USD250 per month. As Kowalski sees it, Canvus customers can instead pay as little as USD3,500 to have their brand displayed at a school or in a community park – about USD11 per month when spread over a 25-year period. The company counts oil giant Shell Plc (whose donations are on display in Texas), car dealership Mark Wahlberg Chevrolet (Ohio) and construction firm Grainger Inc (Illinois) among its customers. Canvus also sells to communities directly.

Since the company started commercial production this summer, Kowalski says it has sold more than 200 products that are now installed across dozens of locations. Canvus also makes money by charging wind farm operators for blade disposal.

All turbine-blade afterlives are not created equal. Some approaches, such as processing the blades into small pieces for kiln fuel, have a sizeable energy footprint, or emit pollutants in the process of burning fiberglass. Canvus incorporates other recycled materials in its benches and planters – including rubber tires, shoes and plastic waste – but the company is still working on a full life-cycle assessment of its products, and hasn’t calculated how much energy is used on blade transportation and processing.

McKinley at Queen’s University Belfast points out another risk for Canvus and businesses like it. Wind turbines run for about 25 years, but that lifespan can be extended under a caring hand or shortened by a malfunction or lightning strike – a challenge for anyone trying to build a stable supply chain. Next-generation recyclable blades could also threaten the long-term prospects of companies focused on upcycling decommissioned ones.

“If you look at the [repurposing] industry as a whole, it would be difficult to really understand what is your total market and how you plan your production around that,” says Tina Hoffman, vice president of corporate communications at MidAmerican Energy.

MidAmerican manages more than 3,400 turbines across Iowa, and in 2021 stopped sending its retired blades to landfills. Last year, Hoffman says the company recycled roughly 1,100 blades, hundreds of which went to Canvus. But MidAmerican is also increasingly focused on maintenance, and wants to reduce the number of blades it needs to dispose of in any given year.

As wind power works through economic growing pains, turbines also still face some local resistance. But where wind farms have stirred up complaints in the US about unappealing aesthetics, Canvus’s products get more positive marks.

“This is definitely a new feature that we’re excited to have,” says Stacy Barnes, a city administrator in Greensburg, Kansas, home to six blade benches donated by renewable energy firms. After a 2007 tornado blew away much of Greensburg’s infrastructure, the town committed to a greener rebuild. Its streets are now lined with energy-saving LED lamps and EV charging stations. The 800-person community is also 100 per cent powered by wind energy.

The wind farms near Greensburg have yet to reach their end-of-life phase, but Barnes says she’s aware of the waste issue associated with retired turbines. “To see a reuse, other than just discarding them, is really great,” she says.