CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida (THE WASHINGTON POST) – The uniforms resemble costumes from the television series “Battlestar Galactica,” and the logo is right out of Star Trek. Even the name given its members, “guardians,” seems born out of science fiction. But three years after it was established as the sixth branch of the US Armed Forces, the US Space Force is very much a reality.

It has a motto, “Sempra Supra” or “Always Above,” fitting for an agency whose future is outside Earth’s atmosphere. It has an official song, a short, melodic anthem about guardians “boldly reaching into space” that’s not as catchy as “The Army Goes Rolling Along.” It has a budget (USD26 billion last year, similar to NASA), bases across the country and a mission to transform the military’s relationship to the cosmos at a time when space has moved from being a peaceful commons to a crucial front in military conflict.

“We are very much clearly in the next chapter of the Space Force,” General David Thompson, the vice chief of space operations, said during a recent event hosted by the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. The mission of the Space Force now is to become an “enterprise that really makes sure that we’re ready to deliver war fighting capabilities.”

What that means in practice is still unclear: The Space Force remains one of the least understood arms of the federal government. Its culture and identity are still being molded, as its leaders push to set the department apart from the Air Force, Navy and Army by arguing that as a new, smaller service it is free to do things differently. While the Air Force has more than 300,000 service members, there are only 13,000 guardians.

Internally, Space Force officials are still debating its priorities, analysts say: Is it to support war fighters on the ground? Or should it focus primarily on protecting assets in space? Or both? And despite all the talk of starting fresh and moving nimbly, the Space Force still exists within the rigid walls of the Pentagon, the world’s largest bureaucracy, which is often faulted for resisting change.

When Space Force General Chance Saltzman, chief of space operations, introduced tenets to guide the force, he labelled them “A theory of success,” rather than a doctrine because he wants them to continue to evolve.

“I’m proposing this theory so that people will debate with me,” he said during an event earlier this year at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “So we’ll get better at figuring out what are the nuances that matter, what are the details that we to continue to refine.”

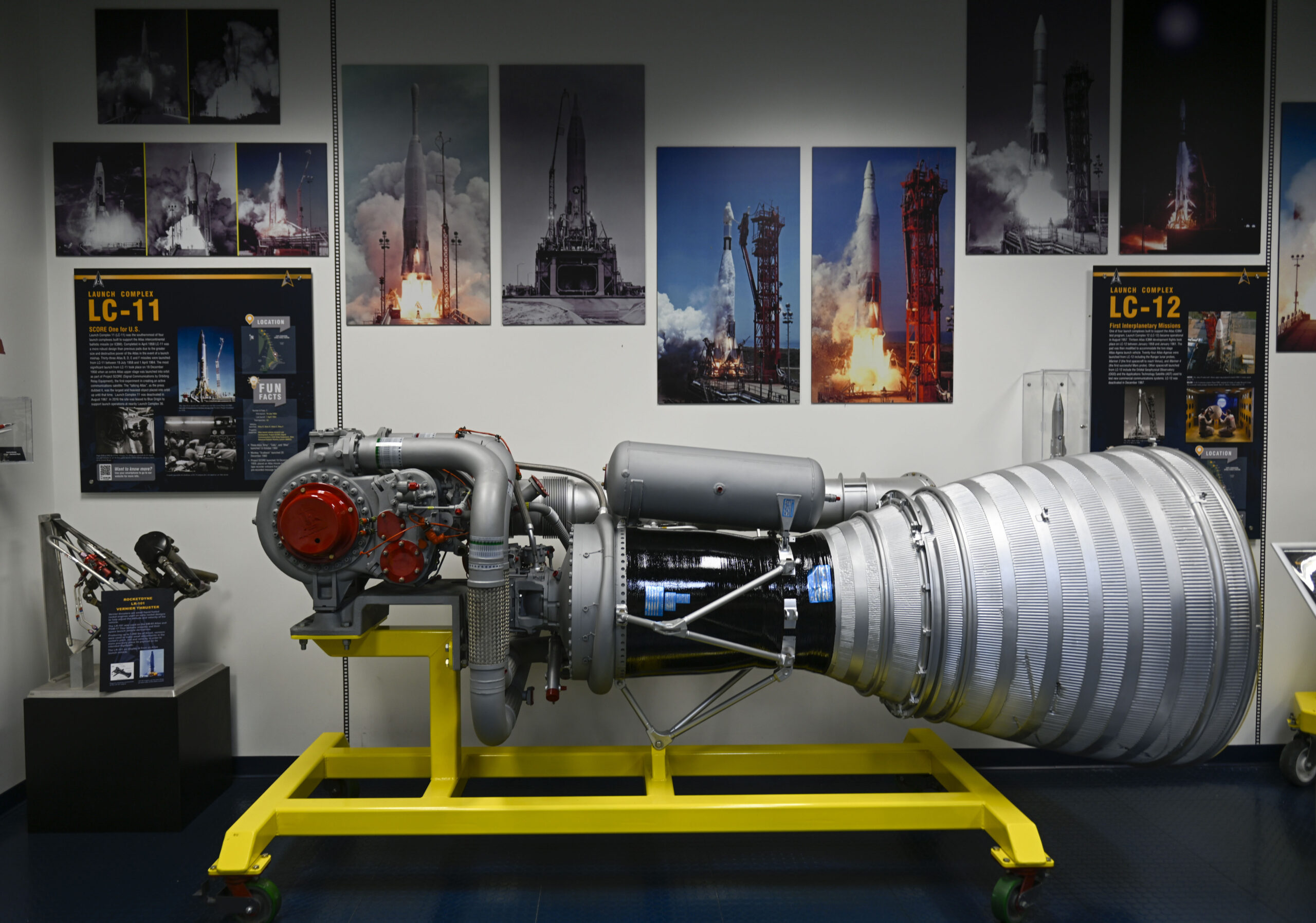

A glimpse of what the Space Force has become, and aspires to, can be seen on the Florida Space Coast, where the Space Age was born in the United States and where a new space era, driven largely by a growth in the private space industry, is taking hold.

Propelled largely by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the number of launches here has not only increased, but the topography of the place has changed. Landing pads for SpaceX’s reusable rockets and historic launch sites – like pad 39A that launched the Apollo astronauts to the moon – are now in private hands.

New companies, such as Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, are taking over launch pads that had sat vacant for decades, trying to get their rockets into orbit as well. Even the official name has changed: It is now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

The growth is remarkable. In 2021, 31 rockets blasted off from the facilities run by NASA and the Space Force. Last year, the number jumped to 57, and this year it’s expected to exceed 90.

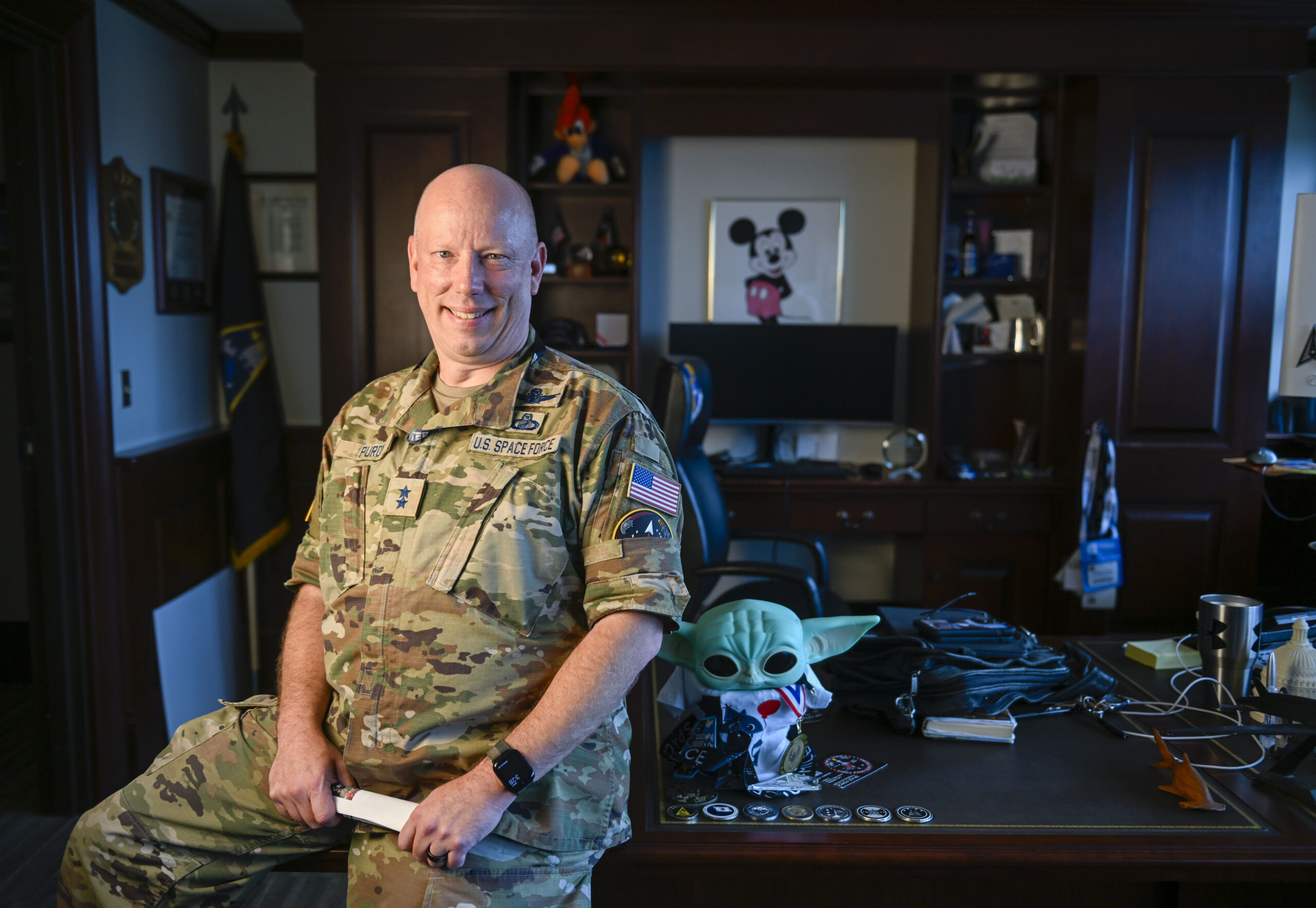

With some thinking that number will eventually exceed 200, 300 or even more, a top Space Force general decided he needed help managing the traffic. So last spring, Major General Stephen Purdy, the commander of the 45th Space Wing, which oversees the base, arranged a meeting for a couple dozen of his staff at a place where many loathe to go but that is used to sending large numbers of vehicles into the sky at a regular cadence: Orlando International Airport.

During the visit to the Orlando airport, “our folks got a lot of good ideas,” he said in an interview in his office at Patrick Space Force Base. “Because these are people they don’t normally talk to. So they do things in a different way. They think a different way.”

What Purdy – and the Space Force as a whole – is trying to do is far more than just create airline-like operations. They are focused on redefining how the military uses space, and attempting to transform it into a domain where the US can exert the kind of tactical dominance it now displays on land, air and sea.

That is easier said than done. Much of the military’s infrastructure in space was developed at a time when space was considered a peaceful place. Satellites, for example, were built to be big and robust and last for years, even decades, without interference. But then China and Russia showed such fat targets were sitting ducks. China blasted a dead satellite with a missile strike in 2007, and Russia did it in 2021 – shows of force that shook the US military leadership and polluted Earth orbit with dangerous debris for decades to come.

So the Space Force is pivoting, relying on constellations of small satellites that can be easily replaced and, to an increasing degree, manoeuvre.

That’s just one example of how the Space Force intends to ensure the US maintains “space superiority,” as its leaders often say, to protect the satellites the Defence Department relies on for warnings of incoming missiles, steering precision-guided munitions and surveilling both friendly and hostile forces. It also could deter conflict in space – why strike a satellite if there are backups that would easily carry on the mission?

In the interview, Purdy gave a tour of some of the roles the Space Force could play, offering a glimpse into its future.

Soldiers and Marines already pre-position supplies and equipment on the ground, he said. Could the Space Force start storing supplies in space and then fly them to hot spots on Earth as well?

“In theory, we could have huge racks of stuff in orbit and then somebody can call those in, saying. ‘I need X, Y, Z delivered to me now on this random island.’ And then, boom, they shoot out and they parachute in and they land with GPS assistance,” he said. “It’s a fascinating thought exercise for emergency response – you know if a type of tidal wave or tsunami comes in and wipes out a whole area.”

The military is also working to harness solar energy in space, and then beam it to ground stations. Could the Space Force use that technology to beam power to remote areas to support soldiers on the ground?

Another idea: If the cadence of launches really does double or triple and the costs continue to come down, could the Space Force start using rockets to deliver cargo across the globe at a moment’s notice?

Soon there could be commercial space stations floating around in orbit. “Can we lease a room?” Purdy said. “Can we lease a module?”

The idea is to use space as if it were any other theatre of war, with supply lines, logistical oversight and tactical awareness of what’s happening day in and day out. But all of that is more difficult in a weightless vacuum that extends well beyond the largest oceans.

“In no other military domain would you take a tank, or an aircraft or a jeep or a ship and gas it up and then say…’Okay you will never refuel it again,'” Purdy had said earlier this year in an interview with the Aerospace Corporation. The military also has the ability to repair tanks and jets. But the vehicles the Space Force depends on – satellites – are different. Refuelling and servicing them are difficult and so every movement has to be considered carefully. “Am I going to need this fuel 10 years from now?” he said in the Aerospace Corporation interview.

Some of these concepts may become real. Some may not. But Purdy at least feels free to pursue new ideas because “we’re not bound by years of tradition within the Space Force or the previous Air Force command,” he said. “It didn’t exist. And so we can define our own concepts of how operations will work.”

Two years ago “we weren’t thinking of any of this stuff, none of it,” he added. “The on-orbit space storage of logistics, we weren’t thinking of six months ago. And so we’ve been able to think rapidly, get with industry and rapidly move the ball forward on all those pieces.”

The fact that the idea of the Space Force is still somewhat in flux is to be expected, said Douglas Loverro, the former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defence for space policy.

After it was founded in 1947, “it took the Air Force 25 years to figure out their mission,” he said. “We shouldn’t expect that the Space Force is going to be able to figure it out the day after we stand them up. It’s going to take a little while, and that’s okay.”

When it was established by President Donald Trump at the end of 2019, the Space Force was widely mocked – derided as a political ploy for a politician desperately trying to project strength and the butt of alien jokes for late-night comedians.

But as it has taken form, the culture of the Space Force “is building, and I think that’s good,” retired Air Force General John Hyten, the former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in an interview. “We just have to change the process along with the culture because you can have a new culture and the old process, and you still run into a brick wall.”

While the Navy patrols vast oceans, the Space Force’s “area of responsibility” is “defined as 100 kilometres above sea level extending outward, indefinitely,” Lieutenant General John Shaw, the Deputy Commander of the US Space Command, said during a recent talk with the Secure World Foundation. “So, a huge AOR. Do the math.”

Another problem, Hyten said, is that so much of what the Space Force does remains classified. “And because it’s overclassified, it’s very difficult to talk about specifics,” Hyten said. “And when you can’t talk about specifics that makes it one of the most misunderstood elements of our government. . . . We fundamentally need to normalise the classification, so we can have a conversation with the public, with the American people.”