ANN/THE STAR – When it comes to renowned clay, no place captures global attention quite like Yixing. Situated in the Yangtze River Delta by Lake Tai in Jiangsu province, this city is hailed as the “Pottery Capital of China.”

Undoubtedly, it stands as the origin of the most prized Chinese teapots.

The mountains in the south-east of Yixing are rich with unique argil, a clay called “Zisha”. Translated into English, it means “Zi”(purple) and “sha” (sand).

Zisha teapots are closely associated with the Gong Fu tea (tea with skill) ritual, which has its origins in Zhangzhou, Fujian province of China, dating back to the late 17th century (1662-1692).

In seeking the perfect teapot and tea making ware during the civil wars of the “Transition Period” (1620-1683), an old master potter named Hui Meng Chen created smaller teapots from “zhuni” (vermillion clay) as compared with the earlier zhisha teapots which were bigger.

The sizes of the other tea utensils followed suit and together they came to be known Gong Fu tea ware which are still used by Chinese tea drinkers today.

But as in all traditions, disputes arose over the origins of Gong Fu tea. Some experts in China were of the view that Gong Fu tea originated in the south-eastern province of Chaozhou and it was relatively unknown outside this area even in the 1950s.

There were also claims, supported by a section of the tea expertise academia in the West, that Gong Fu tea was a relatively recent Taiwanese inventions, influenced by contacts with Japan.

These claims were proven wrong on Aug 4 by four fact-finding experts from China.

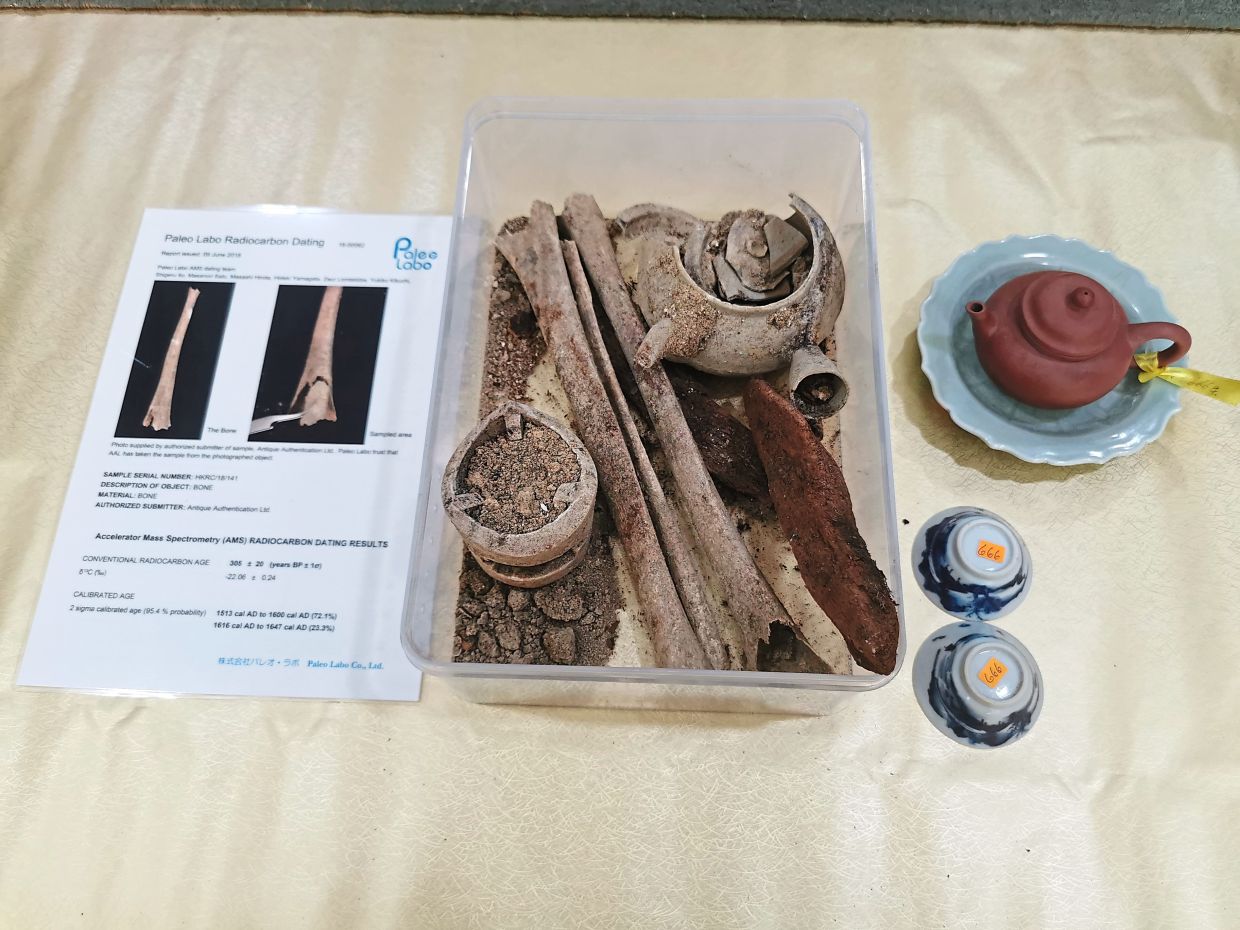

During their mission, Professors Dr Shui Hai Gang, Lin Feng, Wang Ri Gen (from Xiamen University, China) and Yan Li Ren from the Gong Fu Tea Institute of Fujian sifted through the 1,190 unearthed teapots and other earthen and ceramic tea wares of the Ren Fu Collection in Melaka.

They confirmed that teapots, tea cups, dishes, stoves and other paraphernalia of Gong Fu tea could be traced to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties and that the practice extended to overseas Chinese who had migrated to South-East Asia, the region described as “Nanyang” by China.

The Ren Fu Collection began during the 1970s to the 1990s, when ancient graves were demolished to make way for residential and commercial developments in various places in South-East Asia, like Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and other places where the graves of early Chinese settlers were located.

Radiocarbon dating of bone fragment samples found with the unearthed pottery proved that they were from between 1513 and 1647,

Professor Shui, who is the Vice-Director of Xiamen University’s History Department said he and the others were very impressed with what they had seen.

“There is more than enough proof that Gong Fu tea was here from these times and the pottery is certainly from Yixing. The excavated tea wares also reflect the progression of the pottery which came out of China during the period,” he said.

His colleague Prof Wang also concurred that much of the clay used in the unearthed pots originated from Yixing. He said it was rare to find them in such a large collection, adding that he and others were only aware of 28 such items that were archaeologically excavated in mainland China.

Based on previous auctions of rare Yixing teapots, including one made by Chen Ming Yuan, a master craftsman of the Qing dynasty which was sold in 2010 for RMB32.2 million (RM20.4 million), the value of Ren Fu Collection is estimated to be RMB350 million (RM222.4 million).

Tony Gim, owner of the collection, said the investigation by the professors coincided with efforts by China to include Gong Fu tea as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage.

“We have forwarded all the recorded archaeological details and pictures to Xiamen University for study and future research,” he said when presenting a set of unearthed tea wares to Dr Shui.

Traditional tea processing techniques and associated social practices were added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November last year.

These practices are mainly found in the provinces and autonomous regions of Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Hunan, Anhui, Hubei, Shaanxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Fujian, Guangdong and Guangxi. Associated tea rituals are spread throughout the country and shared by multiple ethnic groups.

The history of pottery around Yixing, largely around the settlements of Dingshan and Shushan, now jointly known as Dingshuzhen, dates back to more than six centuries.

There are many types of Yixing clay but they are generally grouped into two grades-earth clay (made from mud) and stone clay (made from rock).

Although “Zisha” is the general term referred to for the raw clay found around Dingshuzhen, besides purple, there are other colours of clay found in the hills of the region. The main ones are “hongni”(red), “zhini”(rose-brown), “zhuni”(vermilion), “banshanlu” (white) and “zhusha” (deep orange-red or the colour of cinnabar).

The zhuni and zhini clays contain high amounts of iron oxide, which gives the teapots their imitable purple-red color but the presence of mica, kaolin, quartz and other minerals also adds to the variety of hues.

The clay is reputedly free of toxic minerals such as lead, arsenic and cadmium.

But porosity is the key reason why zhisa is so highly treasured. The flavours of the tea are absorbed into the unglazed pots, each time the leaves are infused, enhancing the savour.

Connoisseurs swear that if a drinker continuously makes a particular type of tea in a Yixing teapot, pouring hot water into it alone would be enough to get a strong taste of the tea.

Unlike other forms of earthenware, the making of Yixing teapots does not involve the potter’s wheel. The clay is pounded with a heavy wooden mallet into a slab and moulded.

There are three common methods, depending on the shape of the teapots. Round teapots are paddled into shape, the square-shaped are assembled from slabs while those with more than four sides are press-moulded.

The potters use specialised tools of wood, bamboo, animal horns and metals, fashioned over the centuries to make their masterpieces.

According to folklore, tea was discovered accidentally by the Chinese emperor Shen Nong in 2737 BC, when leaves from a tea tree fell into his pot of boiling water.

Captivated by the pleasing aroma and taste, he started experimenting with different kinds of tea leaves.

But tea only became a popular beverage during the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), largely through the influence of Buddhist monks.

As sleeping and eating were strictly prohibited for Buddhists practicing meditation, they could only drink tea, resulting in many becoming tea connoisseurs.

The most important figure in Chinese’s tea history is Lu Yu, often referred to as a “Tea Sage”. The orphan who grew up in a monastery but chose to be a scholar, wrote the monumental Cha Jing (The Way Of Tea) – the first treatise on cultivation, brewing and drinking tea around 760 CE.