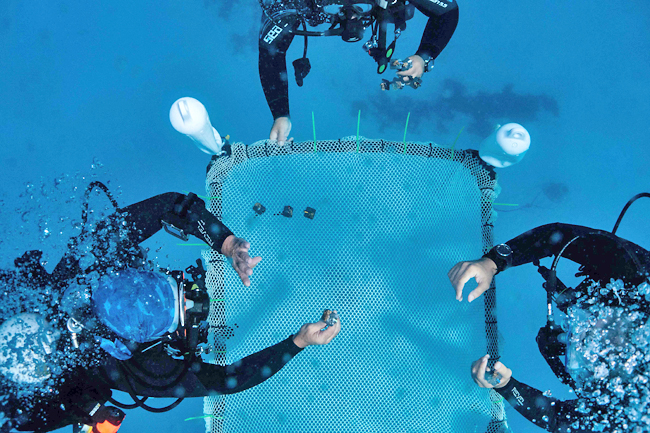

CAPE GRECO (AFP) – It’s a Thursday morning in the tourism hub of Ayia Napa on the southeast coast of Cyprus, and three divers in wetsuits are gluing coral fragments onto numbered pins.

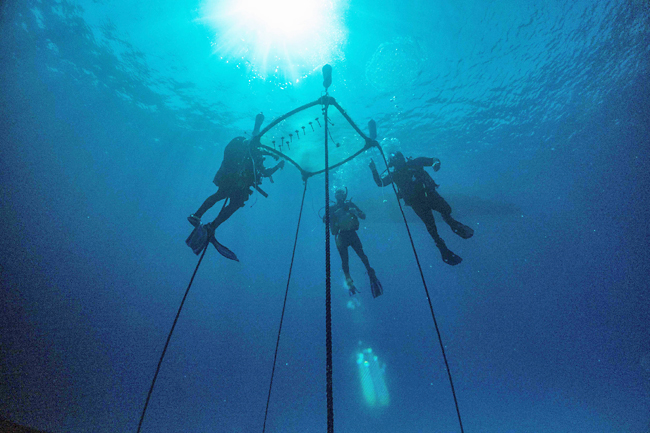

They are preparing to enter the crystal-clear waters and attach the samples to a floating nursery, in a pioneering effort in the Mediterranean to help restore a coral population hit by climate change and unsustainable human activity.

The small fragments of coral have been kept for several weeks at the east Mediterranean island’s Department of Fisheries and Marine Research station.

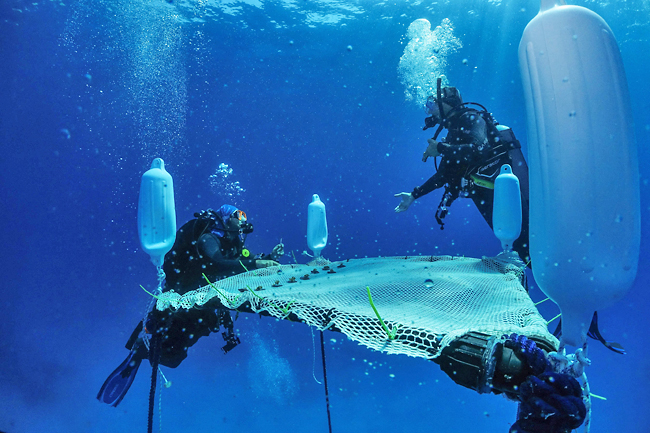

Now they are about to be attached to a net on the underwater nursery some five metres down near Cape Greco.

Senior associate researcher at the Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute, Louis Hadjioannou, is in charge of research into Cladocora caespitosa.

This species – also known as cushion coral – has been declining in the Mediterranean Sea over several years, mainly because of climate change, he said.

And now, he wants to revive it.

The 41-year-old told AFP that in order to do so, the first step is to try to grow the coral in a different underwater habitat “so that we can test whether it is working”.

He said an expert had the idea of using floating nurseries to keep the corals away from potential threats, such as predators.

Cladocora caespitosa is found in shallow waters in Cyprus, generally rocky areas at a depth of up to four metres “where tourists potentially can trample on them”, Hadjioannou said.

By having them floating, you can exclude certain stress factors, including predators and extreme weather conditions.

“It’s a pilot study so we will continue monitoring them on a systematic basis,” he said.

“And in a year’s time we will know basically if the corals are doing well on the nurseries or not.”

This type of floating structure was first created in 2000 at the northern tip of the Red Sea near Jordan, said Buki Rinkevich, the expert behind the idea.

It has been tested worldwide, including in Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Zanzibar, Colombia and Jamaica.

Floating nurseries have produced “good results” with around 100 different species of coral, said Rinkevich, of the National Institute of Oceanography in Haifa.

Hadjioannou said two floating nurseries have been deployed in separate marine protected areas off Cyprus, near Cape Greco and Ayia Napa.

The blocks to which they are moored are at depths of 11 and 17 metres respectively.

At the end of June, 10 coral fragments were installed on each floating nursery, and are being analysed every month or two to check on their condition.

“The plan is to install at least a hundred coral fragments on each floating nursery for this case study,” Hadjioannou said.

If the samples are doing well after a year has passed, “we will collect the coral fragments and transplant them on natural reefs”.

Manos Moraitis, 36, a biologist and associate researcher at the Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute, said the operation is part of the European Union-funded EFFECTIVE project for advancing marine monitoring, restoration, and observation efforts.

Coral reefs are among the planet’s richest and most diverse ecosystems, and home to innumerable aquatic species.

They provide balance and support biodiversity by allowing many species to co-exist, but they are also very sensitive to changes in the environment.

Cypriot marine ecosystems are as much threatened by climate change as they are by mass tourism, coastal development and agricultural pollution.