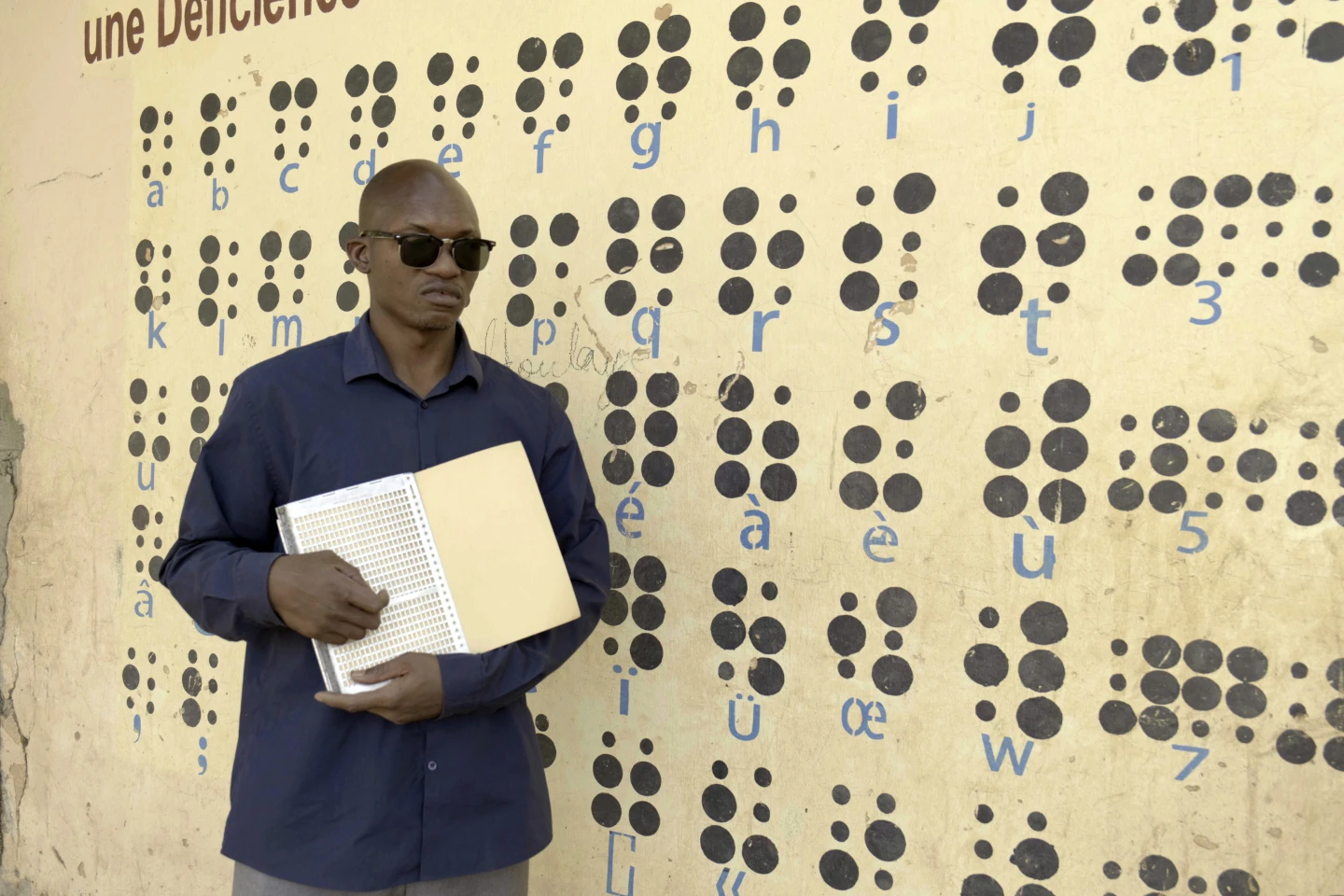

BAMAKO, Mali (AP) — Amadou Ndiaye meticulously ran his fingers across bumps in a piece of paper, making sense of the world he can no longer see.

Two hundred years have passed since the creation of braille, the tactile writing system that has transformed the lives of numerous blind and visually impaired people by providing a path to literacy and independence.

“Braille helped me live my life,” said Ndiaye, a social worker in Mali who lost his eyesight as a child. “Before, people asked themselves the question: Here is someone who can’t see, how will he make it? How will he integrate into society?”

The West African country, with a population of over 20 million people, has long struggled to integrate blind and visually impaired people. According to eye care charity Sightsavers, around 170,000 people in Mali are thought to be blind.

The 47-year-old Ndiaye was fortunate to attend the institute for the blind in Mali, where he learned to write in braille, and told himself: “Really, everything that others do, I can do too.” He later attended university.

He said braille has allowed him to develop his main passion, playing the guitar, which also emphasises the importance of touch.

“Each pressure on the strings, each movement of the finger on the neck, becomes a living note, loaded with meaning,” Ndiaye said.

The guitar plays a crucial role in Mali’s griot tradition, the cultural practice of storytelling through music. Musicians modified the guitar to emulate the sounds of traditional string instruments like the kora. Local artists such as Ali Farka Touré have fused Malian melodies with elements of the blues, producing a soulful, mesmerising sound that has achieved global recognition.

Iconic Malian musical duo Amadou and Mariam awakened Ndiaye’s passion for the instrument when he was a boy.

“One day, near a photography studio, I heard their music resonating through the window, which pushed me to discover this universe,” he said.

Known as “the blind couple from Mali,” the duo of Amadou Bagayoko, who lost his vision at age 16, and Mariam Doumbia, who became blind at age 5 as a consequence of untreated measles, rose to international fame in the 1990s with their fusion of traditional Malian music, rock, and blues.

The couple met at Mali’s institute for the blind, where Doumbia was studying braille and teaching classes in dance and music.

In these locations, braille has enabled students to overcome educational obstacles such as taking longer to learn how to read and write. According to Ali Moustapha Dicko, a teacher at the institute for the blind in the capital, Bamako, they can then take the same exams as anyone else, which allows them to seek employment.

Dicko is also blind. Using a special typewriter, he can create texts in braille for his students. But he says his students are still at a disadvantage.

“We have a crisis of teaching materials,” Dicko said. He has one reading book in braille for his entire class of dozens of students.

But with the development of new technologies, some blind and partially sighted people hope that educational barriers will continue to fall.

“There is software, there are telephones that speak, so there are many things that are vocal,” said Bagayoko of the musical duo. “This allows us to move forward.”

But Moussa Mbengue, the Senegal-based program officer for inclusive education at Sightsavers, said such advances still don’t make the leap that braille did two centuries ago.

“It cannot replace braille. On the contrary, for me, technology complements braille,” he said.