Kristen Millares Young

THE WASHINGTON POST – Werner Herzog has portrayed the poetic excesses of human drama as the brilliant director, producer and screenwriter of more than 60 feature and documentary films, the author of more than 12 books and the director of more than a dozen operas.

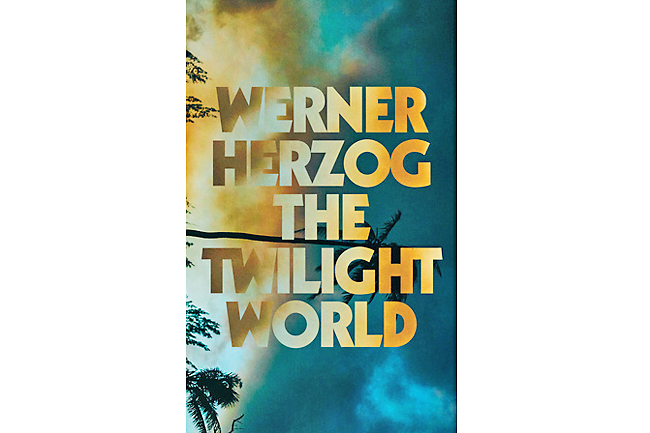

His debut novel, The Twilight World, is a spare and lyric tale about Hiroo Onoda, a real Japanese lieutenant who terrorised the Philippine villagers of Lubang Island with guerrilla tactics for 29 years after World War II’s conclusion.

Much like Herzog’s documentaries, which distill their central inquiries by reenacting fact as fiction beneath his signature philosophical narration, The Twilight World begins with the writer himself.

In Tokyo in 1997 to direct the feudal opera Chushingura, Herzog insults his hosts by declining an invitation from Japan’s emperor. Shocked, someone asks Herzog whom he’d rather meet.

“Onoda,” he replies. “And a week later, I met him.”

Herzog’s hallucinatory account jump cuts to Onoda’s 1974 encounter with Norio Suzuki, a college dropout who travelled to Lubang Island, having made a bucket list for global adventures – Onoda, yeti, panda.

Herzog briefly positions himself as narrator – of insects, he writes, “I start to hear with Onoda’s ears that their humming is not aggressive, is not troubled.” – before slipping into the third person.

Did Onoda long for his family or safety, as he navigated the jungle, changing camps nightly, sometimes walking backward to evade trackers?

The Twilight World largely eschews psychology and self-reflection, both of which Herzog has called “the major catastrophes of the 20th Century”, to chronicle how Onoda and fellow soldiers Shimada and Kozuka cached ammunition in homemade palm oil and misread (as evidence of World War II’s expansion) the planes flying toward subsequent American wars in Korea and Vietnam.

Declining to pass explicit judgment on his subject’s devastating refusal to accept that World War II was over, Herzog nonetheless tightens the lens on who he thinks is important – Onoda. Such foregrounding of one man evokes Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo.

The infamous climax of that story recapitulated the depraved ambitions of a would-be rubber baron who conscripts Indigenous villagers to drag a ship through a steep jungle denuded for that purpose.

In Conquest of the Useless: Reflections From The Making of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog wrote, “The feeling crept over me that my work, my vision, is going to destroy me, and for a fleeting moment I let myself take a long, hard look at myself, something I would not otherwise do – out of instinct, on principal, out of self-preservation – look at myself with objective curiosity to see whether my vision has not destroyed me already.”

Onoda died in 2014 at the age of 91. Public fascination with his story hearkens to a corrupted nostalgia for codes of conduct that demand loyalty to chain of command, no matter what. But where is the honour in ambushing farmers who, recovering from an imposed war, harvest rice?

Left with orders to destroy Lubang Island’s transportation infrastructure but never to surrender or kill himself, Onoda is reported to have killed up to 30 residents, wounding many more, for which he was later pardoned.

Readers of The Twilight World would not learn the human cost of Onoda’s steadfast ignorance because the narrative adheres to his ingenious survival.

Beautifully translated from German into English by Michael Hofmann, The Twilight World reveals the companionship of soldiers with nature and each other but concludes without examining the collective damage wrought by their imperialist fantasy.

Mimicking nesting dolls with an architecture of time from 1997 to 1974 to 1944, where it lingers before boomeranging back, the novel’s construction could have made it possible to see into and around Onoda more.

Herzog’s Onoda is not an ahistorical lunatic, but rather a man with admirable focus who clings to life and refuses to cede a fight. Onoda was weaponised into an instrument of war, a stoic intent that compels Herzog.

“‘Sometimes,’ said Onoda, ‘it feels to me that there is something about these weapons that takes them out of human control. Do they have a life of their own, as soon as they’re devised? And doesn’t War seem to have a life of its own too? Does War dream of War?'”

Having lost his men to surrender and gunfire, Onoda “goes around alertly, sees everything, hears everything. He is always prepared. But he is not allowed to merely be jungle, be a part of nature. He is apart and a part”.

Ignoring found newspapers, dropped leaflets and recordings of his brother’s voice delivered via loudspeaker, he leaves the jungle only in 1974, after Suzuki brings Onoda’s prior commanding officer, age 88, to deliver official orders announcing the end of the war and relieving him of duty.

In his feverish search for ecstatic truths, Herzog has given readers a portal into human folly, self-discipline and domination – surely his life’s work.