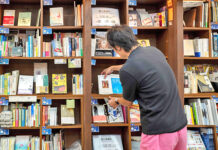

“Throughout my life, I have felt like a book boat,” wrote Jiang Chengbo in the preface of his 2022 memoir

(ANN/THE CHINA DAILY) – The man will be turning 98 this June. Yet, age alone has done little to change his decades-long habit: every day, he will spend about six hours sitting by the glass door of his store, tucked away inside a small alleyway known as the Niujia Lane, on the southwestern part of Suzhou’s Pingjiang Historic District, selling antique books.

Having inherited the store from his publisher grandfather, who founded it in 1899, Jiang moved it to its current location in 2006, before turning it into something of an attraction.

People come here as much for a sighting of the man himself as for the books. His very presence assures them that there’s something unchanging about this part of the town.

One day in April, a woman in her early 40s came in and asked for a specific selection of operatic music scores compiled under the aegis of Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) Emperor Qianlong in the mid-18th century.

She was not to be disappointed. And, as she carefully leafed through the scores, paused at one page and started to sing, the small crowd filling this shoebox of a store fell silent.

The woman identified herself as a Kunqu Opera lover and student of Zhou Qin, an acclaimed master of the much-treasured performing art, who currently teaches at Soochow (Suzhou) University.

A few blocks away, on the Zhongzhangjia Lane of the historical district, lies a museum dedicated to the art form, which first developed in a town near Suzhou around the 15th century.

Covering a total area of 6,000 square metres, the museum’s estate could be traced back to 1887, the year when it first welcomed visitors, as a grand gathering place for all tradesmen in Suzhou who hailed from the northern province of Shanxi.

Many of these men were in banking, their financial clout reflected by the design of the estate’s entrance, the grandiosity of which “contrasted with an understated, typical Suzhou complex entrance”, to quote Pei Hong, a local cultural official.

But, that doesn’t mean that the Shanxi merchants lacked an innate understanding of the importance of localisation.

In fact, the contrary is true. The single most remarkable feature of the entire complex, one that has made it a natural choice for the Kunqu Opera Museum, was an elevated Kunqu Opera stage, constructed right below an elaborately decorated dome, which is said to have functioned as a sound system.

In the old days, those who had absorbed enough singing could retreat to savour tea amid the quietude of the complex’s carefully manicured side garden, which, like all Suzhou gardens, was an exercise in painterly aesthetics, illustrating the nuanced relationship between man and nature.

“Look at the shadow the bamboo groves cast on the wall — so evocative of washed ink splashed across a piece of white silk,” says Ruan Yongsan, a local preservationist.

“The compound was a hybrid, a marriage between the architectural styles of the north and the south. It also epitomised the potent mixture of culture and commerce, for which Suzhou has been known, especially during the past 500 years.”

According to Ruan, in history, the spreading of Kunqu Opera was greatly assisted by the commercial exchanges between Suzhou and the rest of China, which led to its profound impact on other Chinese operatic forms, including Peking Opera.

However, despite being called “the ancestor of all (Chinese) operas”, Kunqu was actually the darling of the elite class: one needs to be well versed in classical literature to be able to relish its deeply poetic lyrics.

“For most of us, it has always been pingtan,” says Ruan.

Literally meaning “to recount and sing (to the strings)”, pingtan has blended several Chinese narrative musical traditions, and enjoyed such sustained popularity in Suzhou over the past centuries that many local residents in their 50s and above had grown up either watching live pingtan performances, or listening to their radio broadcast — or both.

The ageless tales, inspired by a combination of history and legend, were recounted in the Suzhou dialect, with the raconteurs’ unique voices representing, for many young listeners, their initiation into the magical world of storytelling.

Among the art’s young followers is Hu Shuning. While pursuing her studies overseas in 2007, the language student missed her hometown of Suzhou so much, that she sought out online programs teaching the local dialect just to listen. Later, when she decided to become a Suzhou dialect coach herself around 2014, she found herself under the tutelage of some professional pingtan artists.

“These days, there are people among my students who choose to learn the dialect in order to have a deeper appreciation of pingtan,” she says.

Many of them have probably visited one of the pingtan performance venues located within the historical district, or have paid their homage to the Suzhou Pingtan Museum, which opened in 2004 inside the one-time residence of a retired Qing official, just a few steps away from the Kunqu Opera Museum.

“What constitutes our collective memory? The waters and the bridges, of course, but then there are also the sounds — the words spoken and sung and whispered — that we sometimes tend to forget, yet instead have clung to intuitively,” says Hu, who, these days, as a certificated Suzhou dialect teacher, has given lessons to both adults and younger learners. Sometimes she is invited by the management of the historical district to do so.

The 36-year-old was born in Cangjie Street, or the Granary Street, on the western edge of the historical district. For those in the know, the street name is a reflection of ancient Suzhou’s — and by extension, the surrounding region’s — role as a major supplier to the national granary during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties.

About 300 metres east of Cangjie Street is a section of the moat that surrounds the Old Town of Suzhou, the construction of which can be traced back to the fifth century BC.

Ever since, Suzhou, despite the occasional war and intermittent upheavals, had been consistently on the rise, becoming China’s incontestable centre of commerce in the 18th century, during the reign of Emperor Qianlong, who visited the city six times.

Since the 1990s, the senior members of Hu’s family, almost all of whom are involved with the silk weaving industry, have gradually moved out of the city’s Old Town, where the historical district is located. “But I stayed, as well as many of my younger friends,” says Hu. “Why? Because that way, we are more aware of the change of seasons.”

She is referring to the many architectural features of the old residences, including tianjing, a well-like open courtyard located within a building which, by allowing in cool breezes, defuses a hot summer day that would otherwise have been unbearable in the days before air conditioning.

Also in the summer, Hu, the little girl, would be taken by the hand by her father to one of Old Town’s little ports to buy watermelons from the boatmen. Sometimes, there was a young woman in the boat who would beckon at her customers with a short song rendered in all the melodic gentleness of the Suzhou dialect.

Other things were transported by boat too. Where Jiang’s bookstore is standing, a little canal once ran alongside the Niujia Lane, with boats moving languidly along the waterway carrying a wide range of merchandise. Occasionally there would be one loaded with books.

Hence, the comparison with the old man was made between a book boat and himself, who considers it his lifelong mission “to help a good book and an avid reader reach each other”.

These days, when he’s not feeling particularly inclined to venture out, his 68-year-old son Jiang Yilin will be in the store, helping customers, some of whom have a longstanding ledger, while others, like the Kunqu Opera-loving woman, are there for the first time.

“What keeps the heart of a historical district beating?” prompted the younger Jiang. “Sometimes, it could just be the determined, even dogged, effort of one individual who insists on keeping a door open.”