Mark Kennedy

AP – Twenty-seven years ago, Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 saluted men with the right stuff – quiet courage and grace under pressure. This summer, he’s returned to that magic number for a similar rescue tale but traded the vastness of space for a film deep underground.

Thirteen Lives is a dramatisation of what happened in July 2018 when 12 boys and their football coach were trapped in a flooded limestone cave in Thailand for several weeks. Like his space flick, it will take a lot of on-the-fly can-do to get them out.

This particular cave rescue is natural fodder for drama: A group of cave-diving hobbyists from Europe alongside Thai Navy SEALS and hundreds of farmers, engineers and helpers came together for a happy ending – all the boys and their coach survived. (That’s a spoiler if you’ve been in a literal cave for the past four years).

There’s already been a cracking documentary – The Rescue from the Free Solo Oscar-winning filmmaking team of E Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, who used body-cam footage of the rescue – and a Netflix six-part mini series that debuts in September.

Each of those has a focus – The Rescue explores how two slightly odd middle-aged British men became central to the operation, and the upcoming Netflix series will tell the tale from the perspective of the trapped kids.

Howard and screenwriter William Nicholson have admirably widened the scope to include everything from the frantic families and religious figures to the governor, as well as how a water engineer helped the rescue effort by diverting rainfall away from the cave and the farmers who sacrificed their crops to flooding.

The overall effect is a more inclusive storytelling – no white saviour narrative, great – but the cost is a flattening of the narrative.

There are pockets of diffusive heroes everywhere – no bad guys at all, unless you want to blame the rain – and that means a lack of tautness or through-line.

Neither the divers nor kids, government officials nor families and volunteers really come into focus, staying as murky as the miles of submerged cave.

There is also some clunky dialogue and daft Hollywoodisation, like the heavy use of cellos when things get dramatic and the appearance of slo-mo ambulances.

“This could be a long night,” the governor says out loud at the beginning of the crisis, a line unlikely to have ever been uttered at the time.

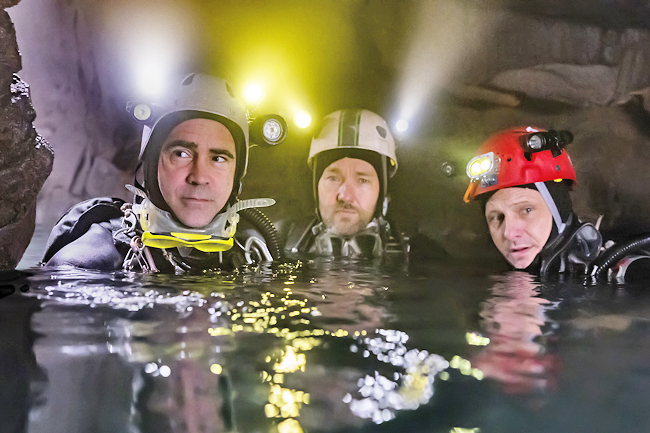

And international film stars Viggo Mortensen, Joel Edgerton and Colin Farrell try hard to be straight-shooting, unglamorous biscuit-eating cave enthusiasts.

“I have zero interest in dying,” Mortensen announces in dialogue that could be ripped from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Farrell has his own: When rescuers debate various rescue solutions, he opines, “Crazy is better than nothing and we’ve got nothing.”

The film gets better once viewers submerge into the flooded cavern and Howard can rely on production designer Molly Hughes and director of photography Sayombhu Mukdeeprom.

Here you can hear the hiss of respirators, the clunk of metal cylinders on rock and divers pushing through tight spaces, a camera impossibly close. Much of the film was shot in Australia, not Thailand.

The very heart of the film is the rather insane-brilliant idea to heavily drug the children before pulling them out, essentially turning each into an inert, pliable weight to be yanked and frequently re-sedated over the several hours spent getting them out.

“They’re packages and we’re just the delivery guys,” one rescuer says.

That makeshift, off-the-cuff solution-finding means the difference between life and death and is also what kept animating Howard’s Apollo 13. Unfortunately, this time underground, he just seems like the delivery guy. Our advice: Fire up the documentary instead.