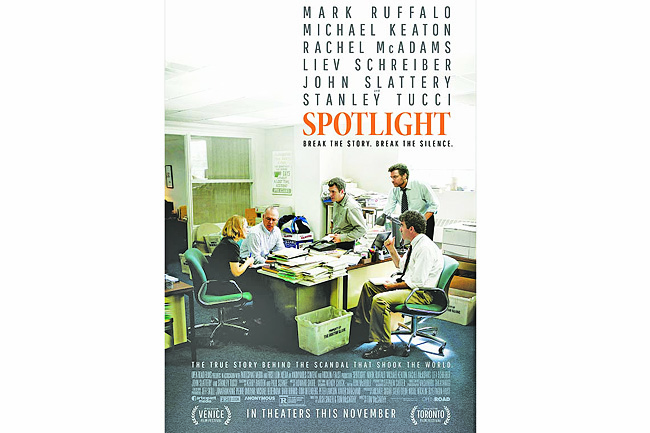

ANN/THE KATHMANDU POST – In 2016, my fascination with the Oscars was unwavering, my devotion absolute, yet I remained blissfully unaware that the revered award was primarily about performance and, frankly, often inconsequential. The contenders for Best Picture that year were impressive – Mad Max,’The Revenant, The Martian – all films whose intensity and spectacle had captured my attention.

To my dismay, the prize went to a subdued and, at the time, dreadfully dull film (admittedly, I was 16 then) – Spotlight.

Spotlight lacked the glitz and glamour I associated with films. Its simplicity didn’t engage me visually, and as a teenager, I found dialogue-heavy films laborious. However, upon revisiting the film after a few years – and still occasionally watching it – I now consider it one of the most deserving Best Picture winners, alongside Moonlight.

Spotlight centres around The Boston Globe’s ‘Spotlight’ team and its investigation into accusations of pervasive and institutionalised child sex abuse by multiple priests in the Boston region.

Much of the film focuses on the journalists – Michael Rezendes, Walter ‘Robby’ Robinson, Sacha Pfeiffer and Matt Carroll – who work day and night for months to build up an air-night story which reveals that the church not only ignored the abuses but protected the accused priests, transferring them from one place to another without any reprimands.

The Boston Globe office – bustling with reporters typing away at their desks, the piles of paper, spiral notebooks, empty coffee cups – emotes a sense of familiarity.

Yet I can’t help but feel jealous of these journalists; their resources are more vast than that of newsrooms in Nepal – a physical archive that one can look into for previous publications, robust physical infrastructure and most importantly, a snack vending machine.

The journalists there are given time – enough of it to delve deep into an issue truly, do months and perhaps years of research, consult with one another and come up with stories that aren’t there to fill pages but do some actual work that is transforming and touching.

Every time I finish watching Spotlight, it leaves me with a sense of heightened awareness, like I’m going to go out into the world, investigate and scoop out the juiciest details within Nepali contemporary society.

This adrenaline is short-lived. I quickly realise that investigative journalism is anything but glamorous; it is, in fact, tedious, slow and really bad for your eyes and back.

Moreover, as the movie also shows – there are multiple instances where the Spotlight team is under fire for their slow efforts and lack of results – that investigative journalism is, to a certain extent, parasitic as it has to survive on the results brought in by other news beats and corporate to survive.

However, as shown by the film, the effort and patience pay off, resulting in powerful journalism that results in systemic change.

The film’s visuals are unremarkable. To people who aren’t enchanted by the air of newsrooms, in fact, it may come off as boring. Unlike in another popular journalism film All The President’s Men, which focuses more on dramatisation, playing of light and shadow (“follow the money”), and suspense, Spotlight is much toned down, and it feels like the audience is witnessing everyday people at work.

The conversations between the characters are what bring about catharsis – Stanley Tucci’s sharp-mouthed lawyer Mitchell Garabedian, in a seemingly insignificant scene at a restaurant, says, “If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one.”

It is within the quietness and everydayness of the characters that the entire movie enfolds, carrying the heavy topic of systemic abuse and paedophilia.

What director McArthy does is show journalists working on the case as a part of the bigger system – thus discouraging the film from becoming a hero’s story – as the Spotlight team investigates that case, all of them are forced to confront their own attachment to the church and the town that has kept the issue under the rugs. – Urza Acharya