Philip Kennicott

NEW YORK (THE WASHINGTON POST) – Perhaps the best way to make sense of the protean creativity on view in the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) Sophie Taeuber-Arp exhibition is a simple list of the kind of work on display.

There are paintings, sculptures, wall hangings, stained glass, marionettes, stage designs, photographs, jewellery, bead work, textiles, line drawings, architectural renderings and furniture. She also designed clothing and worked as a dancer and choreographer.

It is, understandably, a dizzying exhibition, devoted to an artist too long overlooked by the art world; too long in the shadow of her husband, Jean Arp; too long thought of as more of a decorator or craftswoman than one of the great figures of the 20th-Century visual culture.

Organised with the Kunstmuseum in Basel and the Tate Modern in London, the show includes some 300 works, across the many media in which Taeuber-Arp excelled. Many, if not all of them, are in a bright major key, colourful, buoyant and playful. Perhaps because of her early interest in fabric, grids and geometric swaths of colour were elemental to her thinking when she emerged on the scene during the First World War.

So, too, was the boisterous romp of Dada, with its frontal assault on science, rationality and the arrogant political complacency that was sometimes their dark, accompanying specter.

This leaves an impression of an artist who simply bounced through the world, shedding art the way a great, laden apple tree drops fruit in a wind. Taeuber-Arp seems the perfectly artless artist, a designer of spontaneous fluency and effortless improvisation.

Which is exactly the opposite of who she really was. As the curators make clear through careful juxtapositions and archival material, the Swiss-born artist planned many of her works meticulously, creating paper renderings.

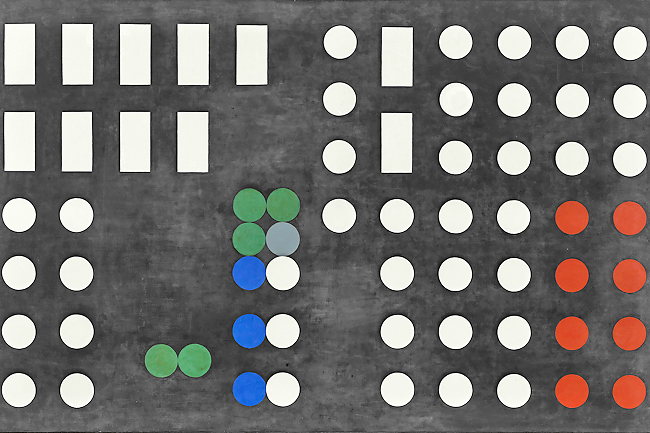

Often, she pursued ideas with small, serial variations, such that each work seems to imply by necessity the design of the next one, rather like an IQ test in which we extrapolate forthcoming patterns by analysing preceding ones.

As Jean Arp once said, “My wife brandishes compass and ruler day and night,” and that is more than evident from the taut perfection of many of her best geometric designs.

Taeuber-Arp was born in Davos, Switzerland, in 1889, long before Davos became synonymous with plutocracy. Her mother encouraged creativity, and Sophie studied in various industrial, design and applied-art schools before becoming active as an artist in her 20s.

She met Arp in 1915, and the two of them moved within artistic circles where disgust with the carnage of war, and the stultifying 19th-Century cultural inheritance that engendered the war, was the foremost driver of artistic vision.

Few artists have so completely inhabited the two basic threads of modernism, impulses that seem in retrospect almost diametrically opposed. In 1918, she began designing marionettes for staging of a commedia dell’arte play called King Stag, a classic Dada performance in which the slightly surreal puppets, confected from tubes, cones and masklike oval faces, included characters such as Freudanalyticus and Dr Oedipus Complex. The marionettes, on view in the MoMA exhibition, are a delight and were embraced as sculpture by the avant-garde even if early performances of the play were closed by the 1918 flu pandemic.

Parallel to the embrace of absurdity, the childlike, the unconscious and what was then called simply the “primitive,” Taeuber-Arp also pursued the linear, rational, even dogmatic orderliness of modernism.

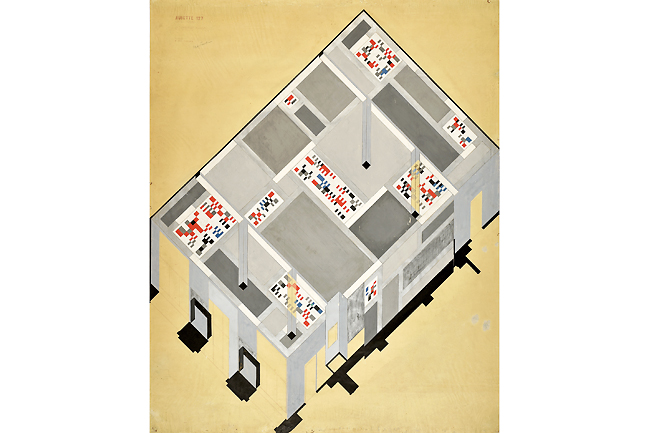

She was an architect who designed her own studio and home, an interior designer who covered walls with grids of colour, and an interior designer who brought a strong sense of purposeful design to domestic space. One work included in the Tate and Basel exhibitions (and included in the substantial catalogue) is a schematic for how to store things in a utility closet that she designed for a 1930s Berlin house. It not only indicates the size and interior shape of the closet, it shows where the brooms, dustpans, brushes, towels, cleaning cloths and even the iron were to be stored.

The MoMA show includes several other fine, axonometric drawings from the same Berlin project (designed for Ingeborg and Wilhelm Bitter), but it’s worth looking up the interior closet rendering. In the modern house, these tools of daily life are almost always banished or invisible. But in this lovely little drawing, Taeuber-Arp has joined the two strains of modernism together, she has given us the waking fantasy of order and geometry, and the hidden “unconscious” of the broom and dustpan. She saw both, she saw the interrelation between them. The old world must be swept out, but there must be space for the broom in the new order that replaces it. She was almost exceptional in that.

Her early work on King Stag helped establish her reputation as an artist. Design work, including interior designs for a cafe and dance hall complex in Strasbourg, France, known as the Aubette, gave her the freedom to pursue painting and sculpture more independently. Much of this large exhibition is given over to paintings and other works made in the 1930s, when she explored and sometimes exhausted different vocabularies of squares and circles, lines and wedges, and unique shapes including a bent-sided form that looks almost as if traced from one of the classic early Dada works, Marcel Duchamp’s 1913-1914 Three Standard Stoppages.

Not much biographical or personal texture about Taeuber-Arp emerges from this exhibition. Her husband is rarely present, despite their having worked together and the substantial overlap in their artist ideals. Mention is made of her drawing on Hopi designs, but mostly, this exhibition situates her within the world from which she was mostly erased, the avant-garde leadership circles of the last century.

She died in 1943, after lighting the fireplace in a guest room while visiting a friend. The flue was closed, and she was asphyxiated by carbon monoxide.

It’s easier to feel admiration for her work, and her inexhaustibility, than love for whomever she was, which isn’t clear from this survey. Her gradual erasure was probably inevitable: She was a woman in a man’s world; she worked in media, including fabric and jewelry, that still struggle for full recognition in the hierarchies of the art world; important work was lost or altered; her husband’s stature partly eclipsed hers; and geometric abstraction was a field crowded with competition.

Photographs made of Sophie Taeuber in 1920 hint at the next stage in the rehabilitation of her legacy. She is seen partly hiding behind one of her most important early works, a small sculpture called simply Dada Head.

The bulbous faux head functions as a mask, and in one image, she also wears a thin veil. She succeeds in conveying a message common to serious artists: that it is the work, not the woman or the man behind it, that matters. But the work leaves us hungry to know her, too.