Rosa Boshier

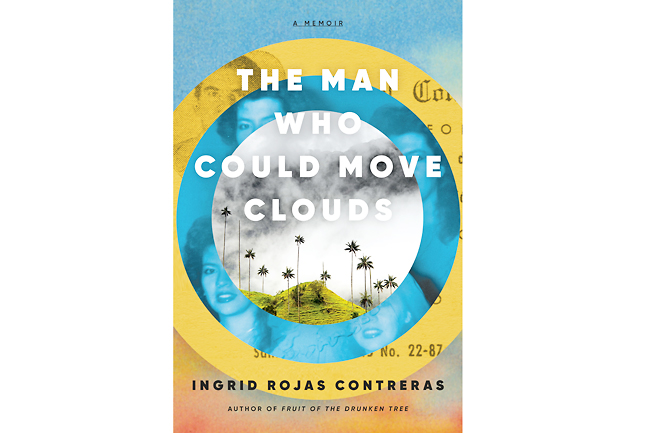

THE WASHINGTON POST – Ingrid Rojas Contreras calls her new book, The Man Who Could Move Clouds “a memoir of the ghostly”.

It tells the story of her grandfather Rafael Contreras Alfonso, or Nono, a Colombian curandero, or healer, who had magical gifts that he passed down to Rojas Contreras and her mother. Nono could speak to the dead and heal the sick. Rojas Contreras’s mother, Sojaila, can see into the future and be in two places at once.

Using symbols, family stories and national history, Rojas Contreras threads other characters in and out of a narrative that focusses primarily on the separate bouts of amnesia that led her and her mother to acquire Nono’s spiritual gifts, and their journey, years later, to exhume his body and properly lay him to rest.

Rojas Contreras temporarily lost her memory after a 2007 bike accident in Chicago, and Sojaila lost her memory in Cúcuta, Colombia, at age eight when she fell down a well.

For both, the experience was a portal into the magical. Sojaila, for example, discovers that she can communicate with spirits as her father could. For Rojas Contreras, losing her memory also means re-learning the rich history and ancestral practices that her mother had forbidden her to reveal.

Rojas Contreras’s family members hid their practice of Indigenous spirituality and healing to avoid persecution.

Yet, after memory loss, Rojas Contreras grows less fearful of the hold that colonial oppression has on her cultural history; she wants to share the family stories. Her mother at first refuses to give her daughter her blessing to write their personal history.

But after Sojaila and her sister have dreams in which Nono entreats them to help him pass onto the afterlife, she and Rojas Contreras travel to Colombia to exhume Nono’s remains and collect the family histories.

The accounts in The Man Who Could Move Clouds come directly from the mouths of those who saw Sojaila appear in two places at once or witnessed Nono moving clouds.

This approach to the factual reveals a fidelity to Rojas Contreras’s upbringing in a house crowded with her mother’s fortune-telling clientele that celebrated the unexplainable and surreal.

According to Rojas Contreras, “magical realism” is more than a literary phenomenon; it’s a mirror to lived experience. The book also speaks to the near-constant violence in Colombia and the national amnesia that has accompanied it.

Beyond a family history, The Man Who Could Move Clouds is about the ways in which this violence can take root in the body.

In the early 1990s, Rojas Contreras and her sister Ximena were nearly kidnapped by guerrillas, prompting her family to leave Colombia in search of safety.

In recalling the psychological toll of living under constant threat, and her family’s subsequent migrations throughout South America, Rojas Contreras wrote, “I saw that crossing a border, starting anew, was the sorcery through which we tried to forget what had happened. But where the mind forgets, the body remembers. The past returns, especially when it is suppressed, like a live wire.”

Yet even the causes of distress become lost in translation between the two worlds that Rojas Contreras bridges. Much to Sojaila’s confusion, her daughters carry childhood trauma into adulthood.

Although ostensibly out of harm’s way, Rojas Contreras shoulders survivor’s guilt and acute anxiety, and her sister Ximena struggles with a life-threatening eating disorder. “What they call an eating disorder,” Rojas Contreras explained to her mother, “you call the spiritual sickness”.

In The Man Who Could Move Clouds, Ingrid Rojas Contreras presents her own family history to probe greater questions of who gets to be remembered and how. Using philosophical and startlingly delicate prose, Rojas Contreras spins colonial history, personal narrative and the magical around the axis of her family story.

The reader feels their soft rotation, like planets around a sun. “Words in my mother’s mouth were once alive in my grandfather’s,” Rojas Contreras wrote toward the end of the book, “and if I speak them now, on this page, this makes a circle”.