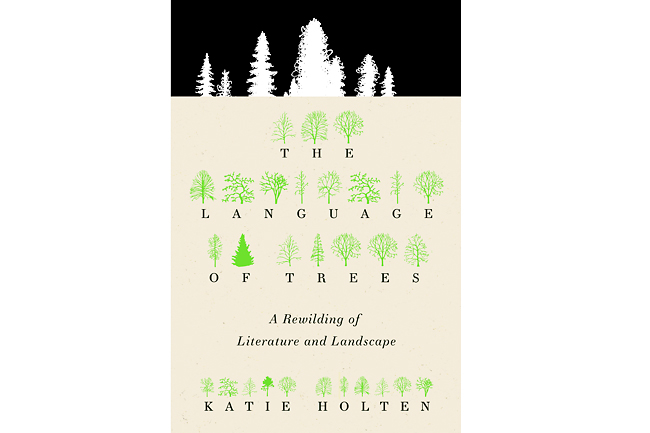

THE WASHINGTON POST – Communicators. Migrants. Soothsayers. Beings more deserving of the rights of personhood than the corporations that have been conferred that legal protection. Editor and artist Katie Holten celebrates all the ways trees are infinitely more complex than commonly envisioned in her new anthology, The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape.

The collection features various writers, including Plato, Elizabeth Kolbert and Aimee Nezhukumatathil, whose contributions are paired with Holten’s forested translations. Holten has designed an entire typeface wherein each letter of the alphabet is assigned a tree whose popular name shares that first letter: “P” is a pine, “E” is an elm and so forth. The book’s poems, quotes and short essays are all translated into Holten’s tree language; the resulting groves illustrate the text. Holten intends for the alphabet to help “those who want to fall in love with the world by rewilding their words”. With these entangled thickets, readers can rethink what constitutes a language.

Contemplating the language of trees “might incline us to be less brutal, less extractive”, wrote poet and essayist Ross Gay in his introduction. “It might incline us to give shelter and make room. The language of trees might incline us to patience. To love. It might incline us to gratitude.”

As in many anthologies, there are moments when the narrative arc commonly expected of book-length works feels more like a winding trail through the woods. But the wet slap of ferns is a good reminder that not all paths should be cleared and that the moments of delight are many. More than informative, The Language of Trees is inspiring; many of its writers merge the lyric with insights that are scientific, intimate and surprising. Among these some 300 pages are gems, including Among the Trees, by the poet Carl Phillips, who plumbs the human connections that can be forged in a forest. “Among the trees loneliness could be itself.”

In his lyric essay “Of Trees in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood; in Sheet-Iron; in Stone; in Mountains; in Stars”, philosopher Aengus Woods traces the historical and etymological through lines of trees to ogham, a medieval alphabet used for Old Irish; it is believed that each letter in the script was named after a tree, akin to Holten’s illustrations in this anthology. Rewilding, then, is a return to ancient wisdom.

Activism animates The Language of Trees, which is published by Tin House, the Portland, Oregon-based independent press. “Don’t / you tell me this is not the same as my story,” Camille T Dungy wrote in a fierce poem with real range. Her Trophic Cascade concluded, “I reintroduced myself to myself, this time/a mother. After which, nothing was ever the same.” Nor should it be.

The consequences of heedlessness are dire and all around us: the heated planet, the worsening droughts and storms, the fires, the clogged air, the poisoned water.

Environmentalist Winona LaDuke begins by decolonising the terminology of time in The Ojibwe New Year, which refuses the Roman calendar that names months in honour of dead emperors and fallen gods: “In an Indigenous calendar,” she wrote, “time belongs to Mother Earth, not to humans”, and so honours what the land is doing in response to the season, such as “Minookamin (the good earth awakening).” Returning to language as a font of sometimes unseen, yet deterministic meanings in Speaking of Nature, author Robin Wall Kimmerer reminded us that by deploying depersonalised pronouns like “its” to make a forest and a copper mine equivalent, “English encodes human exceptionalism, which privileges the needs and wants of humans above all others and understands us as detached from the commonwealth of life.”

A few themes crop up again and again – climate change, in particular – but they feel necessary; what must be remembered bears repeating. In the concluding essay They Carry Us With Them: The Great Tree Migration, author Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder asked readers to consider the implications of trees’ intergenerational migration to habitats that are shrinking too rapidly to make up for the forests that have burned or shriveled beneath the twinned pressures of economic development and global warming.

Succumb not to despair, despite the odds. “There is hope because the women of the rainforest are rising up,” wrote Waorani Indigenous leader Nemo Andy Guiquita in Mujer Waorani/Waorani Women. Erudite, impassioned and intentional, The Language of Trees is a call to action for those who still care.