Jon Gertner

THE WASHINGTON POST – Eleven eventful years have passed since the death of Steve Jobs, the charismatic co-founder of Apple. Jobs helped introduce a succession of products that almost single-handedly made consumer electronics more beautiful and less buggy.

His gifts for packaging and persuasion, however, built on the work of his company’s design guru, Jony Ive, who had an eye for detail and a knack for industrial production.

Together, the duo put forward the idea that their company wasn’t just making innovative technologies.

The magical, minimalist boxes they were selling – clad in white plastic or aluminum; beautiful, functional and delightfully futuristic – could actually change our lives.

No wonder Apple made money under Jobs. What seems surprising, at least in retrospect, is how that era was merely a prelude to the company’s decade-long bull run.

Upon Jobs’s death from cancer, his handpicked successor, Chief Executive Tim Cook, wrote employees a note, “We will honour his memory by dedicating ourselves to continuing the work he loved so much.”

Wall Street had its doubts, but Cook was true to his word. In the years following, the company systematically rolled out improvements to phones and introduced new devices and services.

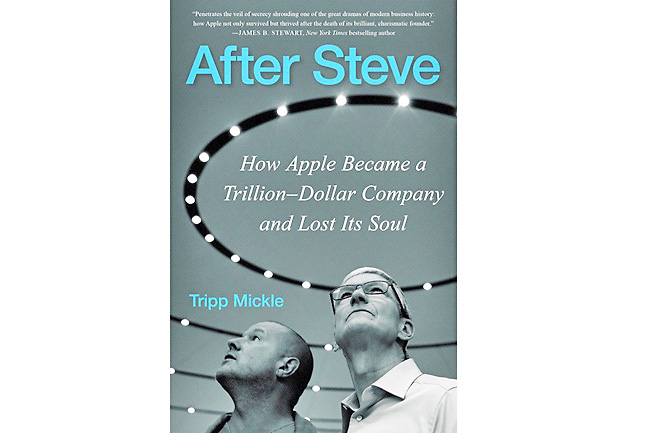

By transforming itself into a global colossus – a “nation-state”, as former Wall Street Journal reporter who recently joined the New York Times Tripp Mickle, called it in his book, After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul – Apple became one of the most successful businesses in history.

Mickle’s exploration of the company’s last decade shows us what happened after Jobs’ demise, as Ive and Cook built on the iPhone’s success. An engrossing narrative that’s impressively reported – an achievement in light of Apple’s culture of secrecy – After Steve takes readers inside the monolithic company. Mickle’s characterisation of Apple’s evolution and its management sometimes seems oversimplified.

Yet his book helps us see why Apple is Apple – that is, how the company mastered the process of making its devices so welcoming and accessible even as they contain the most complex modern technologies imaginable.

After Steve rests on the contention that Apple’s success is difficult to grasp without understanding the chemistry – and, frequently, the tension – between the two men who led the company after 2011.

A native of small-town Alabama, Cook early in his career he excelled at running operations at IBM and Compaq before coming to Apple.

Brilliant, aloof and unflappable, Cook was a kind of anti-Jobs. He was respectful in his bearing and modest in his tastes.

For years Cook preferred living in a small apartment near Apple’s campus and using commercial rather than corporate jets. He dutifully woke up at 4am to check sales reports. And he preferred not to call too much attention to himself.

And yet, in the office, Cook was a dynamo. He seemed capable of maintaining in his working memory a databank of the company’s vast operations, and colleagues quaked in fear during his relentless interrogations at meetings.

Nobody worked harder; nobody knew more about Apple’s corporate circuitry. Nobody understood better how to boost profits.

Ive lived a different life in the same building, floating amid a world of dreamy aesthetes.

During Jobs’s reign, Ive established an autonomous design unit that defined Apple’s aspirations and products.

By the time of Jobs’ death, he was arguably among the most powerful executives at the company, and arousing his displeasure could result in dismissal.

Some of the best passages in After Steve relate to Ive’s sleek and secretive design works, where his team, “a group of Renaissance men devoted to art and invention”, never compromised. That’s because, with soaring iPhone profits, they didn’t have to.

Apple designers set their own hours and sipped rare coffees. They lived “like rock stars”, Mickle explained – always visiting the best restaurants. Ive maintained a serene exterior that belied a fierce and controlling nature.

“He projected the outward persona of a genteel Brit,” Mickle wrote, “unassuming, gracious, and sensitive, but beneath it were the drive, ambition and resolve of a perfectionist who wanted to make products exactly as he imagined them.”

In 2015 Apple, under Ive’s meticulous direction, rolled out a risky new product called the Apple Watch.

The reception for the watch was lukewarm, but over time, as the watch’s health apps and battery life improved, its sales did too.

In the meantime, Cook began to see the potential for Apple in services – apps, streaming music and television shows.

It’s here that the story becomes fraught. As Cook forged ahead, Ive struggled with burnout. And as Apple’s stock price drifted higher, Ive moved further from what he saw as a profit-driven company.

He stopped coming to the office and focussed instead on helping to design Apple’s new corporate headquarters. One of his tasks was a global search for a type of glass so clear it would have the effect, at least in Ive’s view, of bringing greater happiness to Apple employees.

This project eventually cost as much as USD1 billion, Mickle estimates, and constituted “perhaps the largest glass order in history”. Yet it seems to have been Ive’s last eccentric hurrah.

In 2019, with the Apple HQ finished, he resigned. Mickle noted, “Cook, who lived to work, had asked Ive to do the same. He had squeezed more out of the artist than the artist had to give.”

You might wonder if Apple’s history is as tidy as this sounds. Even with its chief designer gone, Apple continued to sell. To those of us on the outside, nothing much changed – the company’s products remained elegant, alluring, reliable.

The argument in After Steve is that Apple’s growth and Ive’s alienation are what caused this great American firm, once so creative and unusual, to lose its soul.

But to buy into this idea one has to believe that a corporation has a soul – a dubious assumption, I think, that echoes Jobs’ old pitch that suggested Apple was more than a company that made money. Rather, it was closer to a spiritual ideal.

It’s never been true, of course. And toward the end of Mickle’s book this notion – Apple as a fallen company, and a fallen ideal – detracts from the compelling narrative.

While the differences between Ive and Cook are real readers may find the lines Mickle draws to be problematic.

The implication that Cook destroyed Apple’s culture, for instance, may seem naive to business-savvy readers, who will view him – correctly, I believe – as a principled CEO who succeeded by respecting his company’s traditions and looking ahead to the demands of consumers, employees and Wall Street. And I suspect readers will have difficulty sympathising with Ive, who seems less the conscience of the company than an industrial designer with an intuitive feel for the market and a predilection for middlebrow culture, like the band Coldplay.

As the years roll by, it’s dismaying to watch Ive’s fixation on luxury grow. It’s not just the famous friends; it’s the custom house in Hawaii, the trips to Europe, the USD300,000 chauffeur-driven Bentley.

All too often Ive comes off less as a visionary than a sybarite. And sometimes his behaviour is repugnant, as when he asks co-workers to fix the soap dispensers on the Gulfstream jet he bought from Laureen Powell-Jobs, Steve’s widow. None of this subtracts from this book’s immense readability. And Mickle’s overreach doesn’t obscure the crisp and detailed view he offers us of Apple’s inner sanctums.

Still, readers of After Steve would do well to remember that no matter the company, soul never figures into the equation – the balance in business between growth and creativity has always been exceedingly difficult to strike. Apple made selling beautiful things seem easy. But really, it only looked that way.