PARIS (AFP) – With the spread of monkeypox across the world coming hot on the heels of COVID-19, there are fears that increasing outbreaks of diseases that jump from animals to humans could spark another pandemic.

While such diseases – called zoonoses – have been around for millennia, they have become more common in recent decades due to deforestation, mass livestock cultivation, climate change and other human-induced upheavals of the animal world, experts say.

Other diseases to leap from animals to humans include HIV, Ebola, Zika, SARS, MERS, bird flu and the bubonic plague.

The World Health Organization (WHO) said on Thursday that it is still investigating the origins of COVID, but the “strongest evidence is still around zoonotic transmission”.

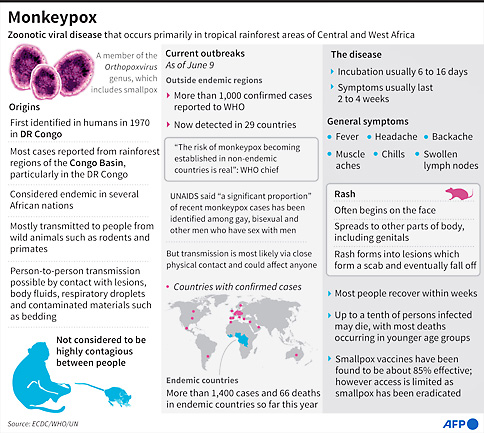

And with more than 1,000 monkeypox cases recorded globally over the last month, the United Nations (UN) agency has warned there is a “real” risk the disease could become established in dozens of countries.

The WHO’s emergencies director Michael Ryan said last week that “it’s not just in monkeypox” – the way that humans and animals interact has become “unstable”.

“The number of times that these diseases cross into humans is increasing and then our ability to amplify that disease and move it on within our communities is increasing,” he said.

Monkeypox did not recently leap over to humans – the first human case was identified in DR Congo in 1970 and it has since been confined to areas in Central and Western Africa. Despite its name, “the latest monkeypox outbreak has nothing to do with monkeys”, said epidemiologist at the University of Cambridge Olivier Restif.

While it was first discovered in macaques, “zoonotic transmission is most often from rodents, and outbreaks spread by person-to-person contact”, he told AFP.

Around 60 per cent of all known human infections are zoonotic, as are 75 per cent of all new and emerging infectious diseases, according to the UN Environment Programme.

Restif said the number of zoonotic pathogens and outbreaks have increased in the past few decades due to “population growth, livestock growth and encroachment into wildlife habitats”.

“Wild animals have drastically changed their behaviours in response to human activities, migrating from their depleted habitats,” he said.

“Animals with weakened immune systems hanging around near people and domestic animals is a sure way of getting more pathogen transmission.”

A specialist in zoonoses at France’s Institute of Research for Development Benjamin Roche said that deforestation has had a major effect.

“Deforestation reduces biodiversity: we lose animals that naturally regulate viruses, which allows them to spread more easily,” he told AFP.

And worse may be to come, with a major study published earlier this year warning that climate change is ramping the risk of another pandemic.

As animals flee their warming natural habitats they will meet other species for the first time – potentially infecting them with some of the 10,000 zoonotic viruses believed to be “circulating silently” among wild mammals, mostly in tropical forests, the study said.

A disease ecologist at Georgetown University Greg Albery who co-authored the study, told AFP that “the host-pathogen network is about to change substantially”.

“We need improved surveillance both in urban and wild animals so that we can identify when a pathogen has jumped from one species to another – and if the receiving host is urban or in close proximity to humans, we should get particularly concerned,” he said.

A specialist in infectious diseases at Britain’s University of Liverpool and the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya Eric Fevre said that “a whole range of new, potentially dangerous diseases could emerge – we have to be ready”.

This includes “focussing the public health of populations” in remote environments and “better studying the ecology of these natural areas to understand how different species interact”.

Restif said that there is “no silver bullet – our best bet is to act at all levels to reduce the risk”.

“We need huge investment in frontline healthcare provision and testing capacity for deprived communities around the world, so that outbreaks can be detected, identified and controlled without delays,” he said.

On Thursday, a WHO scientific advisory group released a preliminary report outlining what needs to be done when a new zoonotic pathogen emerges.

It lists a range of early investigations into how and where the pathogen jumped to humans, determining the potential risk, as well as longer-term environmental impacts.