Marylou Tousignant

THE WASHINGTON POST – It’s no secret: Lucy Stirn loves working at the International Spy Museum in Washington DC. And not just because she gets to tell kids about spies hiding things in fake tiger poop – a highlight of any museum tour.

“You’re never going to have a kid come in and say ‘Oh, that’s boring,’ “ said museum youth education director Stirn which celebrates its 20th birthday this month.

There’s something for everyone among the museum’s 10,000 artefacts. Part of the appeal for kids is “it’s a little naughty and a little sneaky”, said Stirn who was a former teacher who has worked at the museum for 10 years.

“They come in looking for the cool gadgets,” she said. “They don’t know about the historical aspects, so we reveal that, too.”

Visitors are surprised when an object that appears to be one thing turns out to be something very different, said Andrew Hammond, the museum’s artefacts curator and historian.

What looked like tiger poop was actually a device used to detect enemy troop movements in jungles during the Vietnam War (1955-1975). No one ever thought to pick it up and examine it.

“All is not what it seems,” Stirn reminded young visitors. Another example: An ordinary-looking dead rat in an alley might have been gutted to hide money or messages in it. Spies used these rats during the Cold War with the Soviet Union (1945 to 1991).

When stray cats began picking up the rats, agents sprinkled them with hot sauce. Problem solved.

The Soviets turned the tables on United States (US) intelligence in 1945 when some students visiting the American ambassador in Moscow gave him a hand-carved Great Seal of the US.

The attractive gift stayed in his office for seven years, until technicians discovered a bug hidden inside. It took them two months to figure out how it worked.

Many museum exhibits have clever origins. Hammond likes the “amazing” story of pigeons fitted with tiny cameras and released over World War I battlefields to photograph enemy positions.

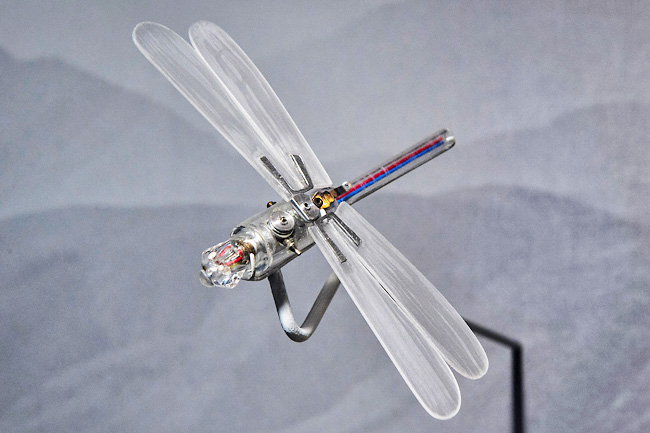

Other artefacts popular with kids include a dragonfly drone, a camouflage suit that makes an agent seem invisible by blending into the background, and a microdot camera that can reduce film images to the size of the period at the end of this sentence.

A special historical artefact is a 1777 letter in which George Washington seeks to start a spy network during the American Revolution.

There are stories and items from many countries and several “try it” challenges such as defusing a bomb (not a real one, of course) and walking like a ninja. Visitors are given agent names and assignments.

The spy museum moved to its current, larger facility in Southwest Washington in 2019. The added space allowed for new displays that go to “the dark side” of espionage, one museum official said.

Controversial topics such as interrogation techniques, leaks of classified information and intelligence failures are now included.

Workshops with older students may feature discussions of ethical (right versus wrong) issues and current news events.

The museum also offers special programmes for people with autism or memory loss. And last year it added a robot, so hospitalised kids can tour the building remotely by controlling where the robot goes and what its camera sees.

It’s just one more supercool thing at the International Spy Museum.