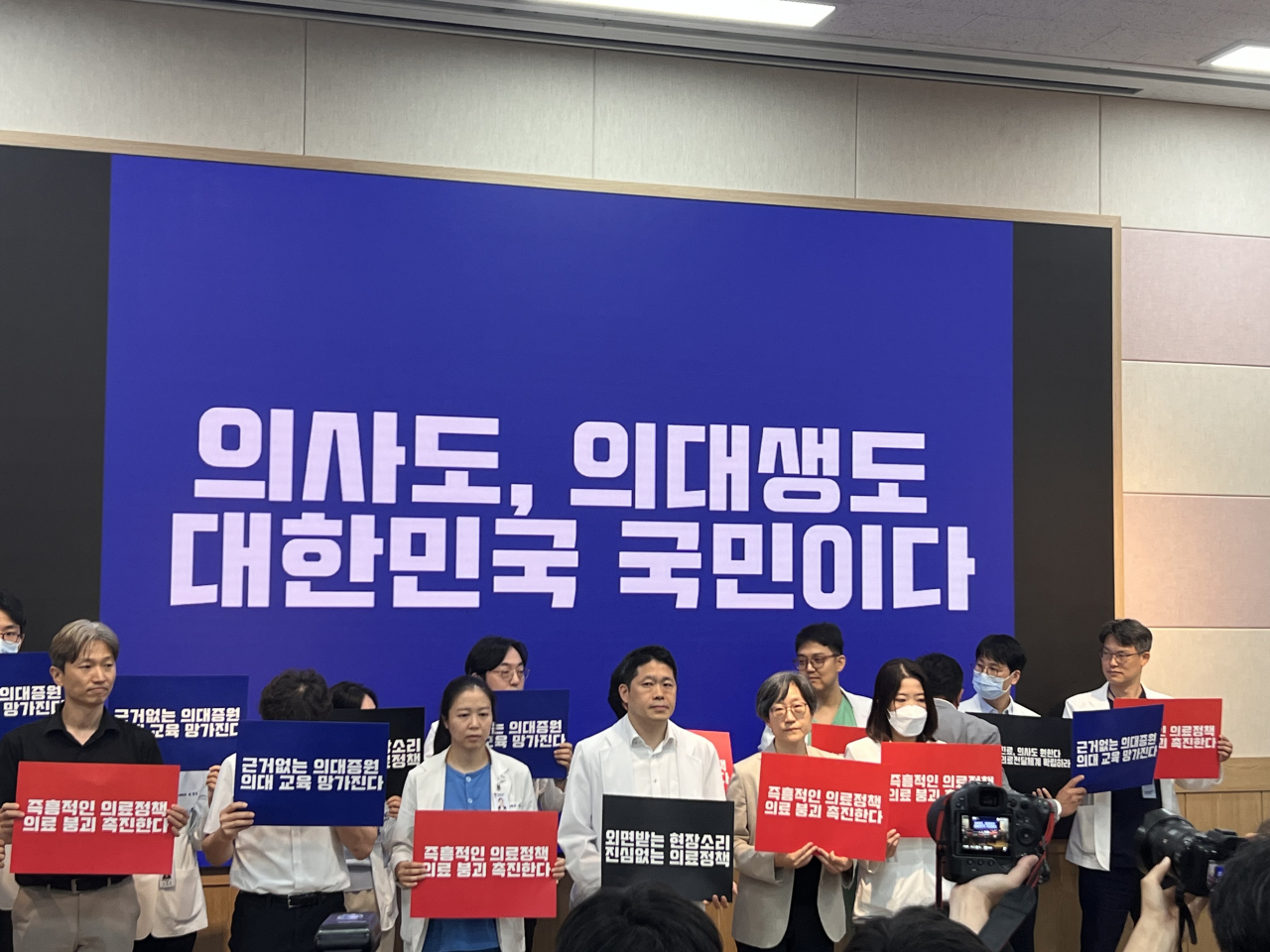

(ANN/THE KOREA HERALD) – In a significant escalation of the ongoing dispute between the government and the country’s medical professional, medical professors at South Korea’s prestigious Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH), began an indefinite strike on Monday.

opposing the government’s plan to expand medical schools. They are the first doctors in South Korea to strike without a time limit, adding to more opposition againts the government’s medical school expansion plant.

The Korea Medical Association, representing 140,000 doctors, will join the action on Tuesday, raising concerns of nationwide medical service disruption.

This will be the largest walkout since 2000, when doctors protested against a government plan to transfer drug dispensing duties to pharmacies.

Initiating the strike, medical professors at SNUH said they had been left with “no choice” but to cease offering care, saying doctors are taking action to salvage the country’s well-regarded health care system.

“Professors, who are unable to tolerate the unreasonable and coercive policies that were announced in February, have decided (to strike),” Kang Hee-gyung, a medical professor specializing in pediatric kidney transplantation, told reporters at a demonstration on the school’s campus.

According to Kang, 529 out of 967 professors at SNU and its affiliated hospitals have pledged to suspend treatment.

The four institutions are Seoul National University Hospital in Seoul, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul Metropolitan Government SNU Boramae Medical Center and SNUH Healthcare System Gangnam Centre.

When trainee doctors previously walked off the job, the operation rate of surgeries for three of the aforementioned hospitals combined fell to 62.7 per cent of the level beforehand.

With further collective action his week, that number falls to 33.5 per cent, according to the emergency committee of medical professors at Seoul National University and Seoul National University Hospital.

However, the planned shutdown of operations does not include suspending medical services and operations for emergency cases, severely ill patients or those hospitalised, Kang said.

Instead, professors will ponder how to create a better medical system for the public and the country’s future, according to Kang.

To minimise the walkout’s impact, the government called on leaders of the hospitals to not authorise the strike and to consider requiring medical professors to compensate for losses sustained by the hospitals due to the collective action.

Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency Commissioner Cho Ji-ho also said police would take stern action by law against any illegal acts connected with the planned strike on Tuesday by the KMA and other doctors’ organisations.

The Health Ministry also filed a report against the KMA with the antitrust regulator on Monday, claiming its role in leading doctors’ strikes violates both criminal and health law.

The country’s Fair Trade Act prohibits business associations from “unfairly restricting competition or limiting the activities of individuals.”

Despite doctors’ pleas, patients have been calling for their doctors to return, while public response remains lukewarm.

On the day of the walkout, the Korean Alliance of Patients Organisations urged the SNU professors to reverse their decision, criticizing them for using patients as leverage to pressure the government.

“It’s hard for patients to understand why the committee had to choose an indefinite strike to achieve their goals. Should nonurgent patients or those with mild illnesses receiving treatment at hospitals affiliated with SNU bear the brunt of the strike and feel anxiety?” the statement read.

Kwak Jae-gun, a professor specialising in pediatric thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at SNU, however, asked patients and their families to be patient, saying they were dealing with “life-and-death issues.”

“(Doctors) have done everything to stop the medical crisis, but the government keeps reiterating the same message like a parrot, vilifying doctors and saying we are raising a turf war for profit,” Kwak said, reading a letter to his patient.

“Seung-yeon’s mom and dad, please hold on just a little. There needs to be someone who should speak out on something when it’s wrong, especially when dealing with life-and-death issues,” Kwak added.

As the government struggles to bridge the gap between the medical community’s demands, which include revisiting the expansion plan and canceling all penalties against trainee doctors, Bang Jae-sung, a committee executive, added that the indefinite strike was a “last resort” to address the current medical crisis.

“Professors will do our best (to stop the situation). But if the government continues to ignore us until the very end and junior doctors and students reject the call to return, then that will be when we would have to kneel to the government and return to patients,” Bang noted.

Amid the intensifying medical standoff, walking off the job to protest against the government appears to be causing rifts within the medical community.

In a contribution sent to his colleagues on Monday, Hong Seung-bong, an epilepsy professor at Samsung Medical Center, urged doctors to return, saying that increasing the number of doctors by “one per cent” will not ruin the country’s health care system.

“The medical circle’s collective leave is tantamount to a death sentence for severely ill patients. … Putting patients’ lives in danger to prevent an increase of 1,509 slots in the medical school enrollment quota is something that should never be done.”