AFP – Sprawled on rocky ground far from sea ice, a lone Canadian polar bear sits under a dazzling sun, his white fur utterly useless as camouflage.

It’s mid-summer on the shores of Hudson Bay and life for the enormous male has been moving in slow motion, far from the prey that keeps him alive: seals.

This is a critical time for the region’s polar bears.

Every year from late June when the bay ice disappears – shrinking until it dots the blue vastness like scattered confetti – they must move onto shore to begin a period of forced fasting.

But that period is lasting longer and longer as temperatures rise – putting them in danger’s way.

Once on solid ground, the bears “typically have very few options for food”, explained a biologist with Polar Bears International (PBI) Geoff York.

York, an American, spends several weeks each year in Churchill, a small town on the edge of the Arctic in the northern Canadian province of Manitoba. There, he follows the fortunes of the endangered animals.

This is one of the best spots from which to study life on Hudson Bay, though transportation generally requires either an all-terrain vehicle adapted to the rugged tundra, or an inflatable boat for navigating the bay’s waters.

York invited an AFP team to join him on an expedition in August.

Near the impressively large male bear lazing in the sun is a pile of fishbones – nowhere near enough to sustain this 11-foot, 1,300-pound beast. “There could be a beluga whale carcass they might be able to find, (or a) naive seal near shore, but generally they’re just fasting,”

York said. “They lose nearly a kilogramme of body weight every day that they’re on land.”

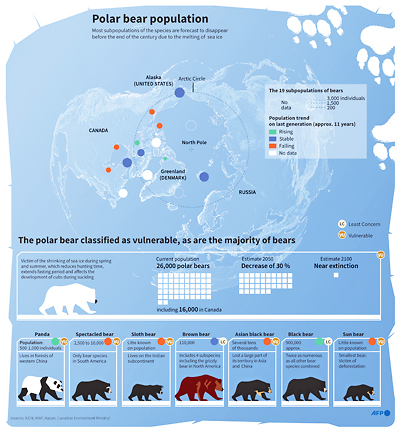

Climate warming is affecting the Arctic three times as fast as other parts of the world – even four times, according to some recent studies. So sea ice, the habitat of the polar bear, is gradually disappearing.

A report published two years ago in the journal Nature Climate Change suggested that this trend could lead to the near-extinction of these majestic animals: 1,200 of them were counted on the western shores of Hudson Bay in the 1980s.

Today, the best estimate is 800.

Each summer, sea ice begins melting earlier and earlier, while the first hard freeze of winter comes later and later.

Climate change thus threatens the polar bears’ very cycle of life.

They have fewer opportunities to build up their reserves of fat and calories before the period of summer scarcity.

The polar bear – technically known as the Ursus maritimus – is a meticulous carnivore that feeds principally on the white fat that envelops and insulates a seal’s body.

But these days, this superpredator of the Arctic sometimes has to feed on seaweed – as a mother and her baby were seen doing not far from the port of Churchill, the self-declared ‘Polar Bear Capital’.

If female bears go more than 117 days without adequate food, they struggle to nurse their young, said Steve Amstrup, an American who is PBI’s lead scientist. Males, he added, can go 180 days.

As a result, births have declined, and it has become much rarer for a female to give birth to three cubs, once a common occurrence.

It is a whole ecosystem in decline, and one that 54-year-old York – with his short hair and rectangular glasses – knows by heart after spending more than 20 years roaming the Arctic, first for the ecology organisation WWF and now for PBI.

During a capture in Alaska, a bear sunk its fangs into his leg.

Another time, while entering what he thought was an abandoned den, he came nose-to-snout with a female. York, normally a quiet man, said he “yelled as loud as I ever have in my life.”

Today, these enormous beasts live a precarious existence.

“Here in Hudson Bay, in the western and southern parts, polar bears are spending up to a month longer on shore than their parents or grandparents did,” York said.

As their physical condition declines, he said, their tolerance for risk rises, and “that might bring them into interaction with people (which) can lead to conflict instead of co-existence”.

Binoculars in hand, Ian Van Nest, a provincial conservation officer, keeps an eye out through the day on the rocks surrounding Churchill, where the bears like to hide.

In this town of 800 inhabitants, which is only accessible by air and train but not by any roads, the bears have begun frequenting the local dump, a source of easy – but potentially harmful – food for them.

They could be seen ripping open trash bags, eating plastic or getting their snouts trapped in food tins amid piles of burning waste.

Since then, the town has taken precautions: The dump is now guarded by cameras, fences and patrols. Across Churchill, people leave cars and houses unlocked in case someone needs to find urgent shelter after an unpleasant encounter with this carnivore.

Posted on walls around town are the emergency phone numbers to reach Van Nest or his colleagues.

When they get an urgent call, they hop in their pickup truck armed with a rifle and a spray can of repellent, wearing protective flak jackets. Van Nest, who is bearded and in his 30s, takes the job seriously, given the rising number of polar bears in the area.

Sometimes they can be scared off with just “the horn on your vehicle”, he told AFP.

But other times “we might have to get on foot and grab our shotguns and cracker shells”, which issue an explosive sound designed to frighten the animal, “and head onto the rocks and pursue that bear”.

Some areas are watched more closely than others – notably around schools as children are arriving in the morning “to ensure that the kids are going to be safe”.

There have been some close calls, like the time in 2013 when a woman was grievously injured by a bear in front of her house, before a neighbour – clad in pajamas and slippers – ran out wielding only his snow shovel to scare the animal away.

Sometimes the animals have to be sedated, then winched up by a helicopter to be transported to the north, or kept in a cage until winter, when they can again feed on the bay.

Churchill’s only “prison” is inhabited entirely by bears, a hangar of 28 cells that can fill up in the autumn as the creatures maraud en masse around town while waiting for the ice to re-form in November.

The fate of the polar bear should alarm everyone, said Flavio Lehner, a climate scientist at Cornell University who was part of the expedition, because the Arctic is a good “barometer” of the planet’s health.

Since the 1980s, the ice pack in the bay has decreased by nearly 50 per cent in summer, according to the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre.

“We see the more – the faster – changes here, because it is warming particularly fast,” said Lehner, who is Swiss.

The region is essential to the health of the global climate because the Arctic effectively provides the planet’s air conditioning. “There’s this important feedback mechanism of sea ice and snow in general,” he said, with frozen areas reflecting 80 per cent of the sun’s rays, providing a cooling effect.

When the Arctic loses its capacity to reflect those rays, he said, there will be consequences for temperatures around the globe.

Thus, when sea ice melts, the much darker ocean’s surface absorbs 80 per cent of the sun’s rays, accelerating the warming trend.

A few years ago, scientists feared that the Arctic’s summer ice pack was rapidly reaching a climatic “tipping point” and, above a certain temperature, would disappear for good.

But more recent studies show the phenomenon could be reversible, Lehner said.

“Should we ever be able to bring temperatures down again, sea ice will come back,” he said. That said, the impact for now is pervasive.

“In the Arctic, climate change is impacting all species,” said Jane Waterman, a biologist at the University of Manitoba.

“Every single thing is being affected by climate change.”

Permafrost – defined as land that is permanently frozen for two successive years – has begun to melt, and in Churchill the very contours of the land have shifted, damaging rail lines and the habitat of wild species.

The entire food chain is under threat, with some non-native species, like certain foxes and wolves, appearing for the first time, endangering Arctic species. Nothing is safe, said Waterman, from the tiniest bacteria to enormous whales.

That includes the beluga whales that migrate each summer – by the tens of thousands – from Arctic waters to the refuge of the Hudson Bay. These small white whales are often spotted in the bay’s vast blue waters.

Swimming in small groups, they like to follow the boats of scientists who have come to study them, seemingly taking pleasure in showing off their large round heads and spouting just feet from captivated observers.

The smallest ones, grey in colour, cling to their mothers’ backs in this estuary, with its relatively warm waters, where they find protection from killer whales and plentiful nourishment. But there has been “a shift in prey availability for beluga whales in some areas of the Arctic”, explained Valeria Vergara, an Argentine researcher who has spent her life studying the beluga.

As the ice cover shrinks, “there’s less under the surface of the ice for the phytoplankton that in turn will feed the zooplankton that in turn will feed big fish”, said Vergara.

The beluga has to dive deeper to find food, and that uses up precious energy.

And another danger lurks: Some climate models suggest that as early as 2030, with the ice fast melting, boats will be able to navigate the Hudson Bay year-round.

Sound pollution is a major problem for the species – known as the “canary of the seas” – whose communication depends on the clicking and whistling sounds it makes.

The beluga depends on sound-based communication to determine its location, find its way and to locate food, Vergara said. Thanks to a hydrophone on the ‘Beluga Boat’ that Vergara uses, humans can monitor the “conversations” of whales far below the surface.

Vergara describes their communications as “very complex”, and she can distinguish between the cries made by mother whales keeping in contact with their youngsters.

To the untrained ear, the sound is a cacophony, but clearly that of an animated community.

Scientists wonder, however, how much longer such communities will last?