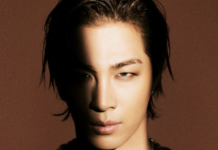

HANOI (AFP) – As a young woman, Tran To Nga was a war correspondent, a prisoner and an activist. Now, at 81, she is waging a court battle against United States (US) chemical firms to win justice for the Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange.

Nga is the first and only civilian to bring a lawsuit against the 14 multinational chemical firms, including Dow Chemical and Monsanto, that produced and sold the toxic herbicide sprayed over Vietnam by US forces during the war.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), some batches of Agent Orange were contaminated with a dioxin – a highly toxic environmental pollutant – that is being investigated for its link to certain types of cancer and to diabetes.

In May 2021, a French court threw Nga’s case out. But she refuses to give up.

“I will not stop. I will be on the side of the victims until my last breath,” Nga, visiting Hanoi from her home in Paris, told AFP.

“This will be my last fight, and the most difficult of all,” said Nga, herself a victim of Agent Orange who spent nine months behind bars, imprisoned by the South Vietnamese regime for her suspected connections to high-ranking communist leaders.

The activist gave birth to her youngest daughter in prison, before being freed when the communists defeated US-backed South Vietnam on April 30, 1975.

Like many other first-generation victims, Nga was at first unaware she had been exposed.

In her mid-20s, she was stationed at a Viet Cong military base near Saigon – now known as Ho Chi Minh City – as a trainee journalist working for Hanoi’s Liberation News Agency.

Coming out of an underground shelter one day, Nga was “covered with a wet powder from a US aircraft”.

“I took a shower only when I was told that it was herbicide all over my body. But then forgot all about it,” she said.

Between early 1962 and 1971, US warplanes dropped about 68 million litres of Agent Orange – so-called because it was stored in drums with orange bands – to defoliate jungles and destroy Viet Cong crops.

At that time, no-one knew they had been exposed to a substance that many believe destroyed not only their lives, but also their children’s and grandchildren’s.

A year after the exposure, in 1968, Nga gave birth to her first baby, a girl born with a congenital heart defect who survived for just 17 months.

“For so long, I blamed myself for being a bad mother, giving birth to a sick baby and not being able to save her,” Nga told AFP.

Nga only suspected her child was a victim of Agent Orange decades later when she encountered veterans and their disabled children in a similar situation.

Vietnam’s Association of Victims of Agent Orange said 4.8 million people were directly exposed, and more than three million have developed health problems.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs has said it assumes – although there is no official scientifically proven link – that some cancers, diabetes and birth defects are associated with Agent Orange exposure.

It has also recognised a link among veterans’ children to spina bifida – a spine defect in a developing foetus.

Nga herself is suffering from effects including type 2 diabetes and cancer.

“I think of Agent Orange as the ancestor for all sorts of other substances that have destroyed the environment,” Nga said.

At a state-sponsored facility caring for Agent Orange victims in the suburbs of Hanoi, Nga watched a computer lesson given by Vuong Thi Quyen.

Quyen, 34, was born with a deformed spine after her soldier father was exposed during the war.

“I am so happy to meet Nga, my idol. She has done so much for victims of Agent Orange like ourselves,” Quyen told AFP.

After the war Nga, a trained chemist, spent many years as a head teacher at a school in Ho Chi Minh City before assuming a role as a go-between for donors in France and Agent Orange victims in Vietnam.

“I have no hatred towards the American government or people. It’s only those that caused devastation and pain that should pay for what they did,” Nga said.

At the trial in France, the multinationals argued that they could not be held responsible for the way the US military used their product, with the court ruling they had been “acting on the orders of” the US, and were therefore immune from prosecution.

Nga said she had been offered “a lot of money” to settle the lawsuit, but “I refused to accept”.

She has since started a crowdfunding campaign to finance an appeal, scheduled for 2024.

So far, only military veterans from the US and its allies in the war have won compensation over Agent Orange.

In 2008, a US federal appeals court upheld the dismissal of a civil lawsuit against major US chemical companies brought by Vietnamese plaintiffs.

“The fight to get justice for Agent Orange victims will last a long time,” Nga said. “But I think I have chosen the correct path.”