ANN/ CHINA DAILY – For 62-year-old Kuai Zhenghua, a national-level inheritor of Huizhou wood carving from Huangshan, Anhui province, restoring ancient wood carvings is like solving a mystery. It requires a combination of experience, intuition, and imagination.

One example involved restoring a carving with traces of an elephant farming scene. Kuai instantly recognised it as a depiction of the legendary ruler Shun, believed to have lived over 4,000 years ago.

“It’s a famous story about the cultural importance of filial piety,” Kuai explained. “I’ve seen so many carvings of it that I can recognise it at a glance. In the story, Shun’s devotion to his parents was so great that it moved heaven, leading elephants to farm for him. The legendary ruler Yao, Shun’s predecessor, heard of this and visited to assess Shun’s character before passing the leadership onto him.”

“Although there are often many missing parts, clues remain. For example, even if the heads of some figures are gone, you can still see their feet and clothing. Men often have bigger feet than women. Farmers don’t wear long robes, but officials do. Women’s costumes often have ribbons. Since these carvings usually depict legends, with clues like these, you can figure out which stories they are about,” Kuai continued.

Once he understands a carving’s content, he can restore it. The pieces he has worked on over the last four decades once decorated the buildings of Huizhou, a historical prefecture, which straddled the border between southern Anhui and northern Jiangxi provinces and covered the area of modern-day Huangshan.

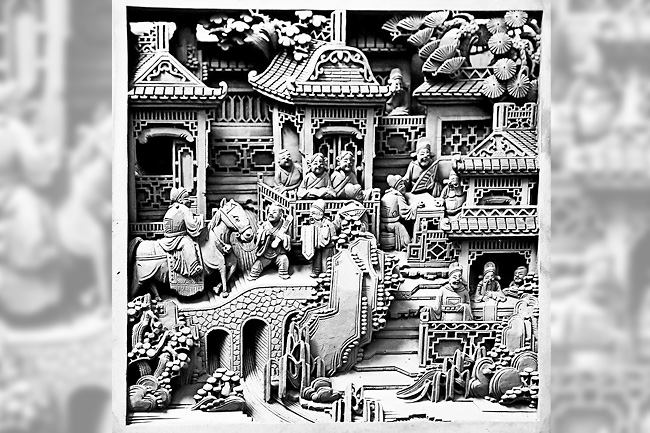

Stone carvings, brick carvings and wood carvings, collectively referred to as the “three carvings” in Huizhou, have been integral components of Huizhou’s architecture since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Different types of carving work in coordination and are used in different parts of buildings, giving rise to the elegant, exquisite decor for which Huizhou architecture is known, said Deputy Secretary-General of Huangshan Intangible Cultural Heritage Research Association Chen Zheng.

The historical buildings are often found nestled in mountainous areas. Residential buildings, one of the most important typologies, are enclosed by walls and look simple from the outside, but inside, they are open, spacious and intricately decorated.

Chen said that the popularity of the “three carvings” is closely related to the rise of Huizhou’s merchants, a class reputed for their honesty and morality during the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

Since Huizhou is a mountainous area with few flat areas for farming, its people often left the region to do business at a young age. When they achieved success and wanted to build homes for their twilight years, lack of land meant they could not build bigger buildings and so instead, they resorted to luxurious decoration to display their hard-earned prosperity.

Wood carving is widely believed to be the most important among the “three carvings”.

“People often say, ‘even if the walls collapse, Huizhou houses will not’, because their wooden structures make use of sunmao (mortise-and-tenon) joints. That’s why for interior decoration, the wooden beams and window lattices are the primary choices, and that’s where wood carving comes into play,” said Chen.

He further explained that brick carvings typically adorn the entrances of ancient residences to signify the owners’ status, while stone carvings are commonly found on pillar bases and are more prevalent in ancestral temples and on paifang, memorial arches.

LASTING INFLUENCE

Chengzhi Hall in Huangshan’s Yixian county is a classic example of Huizhou architecture.

The former residence of Qing Dynasty salt merchant Wang Dinggui, it is known for its outstanding wood carvings. Visitors often feel their eyes can barely take in all the beautiful examples around the complex.

One beam in the main hall is decorated with a carving depicting a Tang Dynasty (618-907) prince’s party, which many officials are attending.

The carving is intricate, and all the figures are painstakingly carved, including the servant in the right corner brewing tea, and another in the left corner cleaning the ears of an official.

The carving symbolises the owner’s wish to become an official, said Vice-President of the Yixian Huihuang Tourism Development Group Huang Jie, which was responsible for promoting scenic spots in the area.

She explained that the carvings embody Wang’s aspirations.

Beyond conveying his ambition to attain an official position, they also symbolise his drive for prosperity in business, his wishes for the longevity of elderly relatives, and his desire for the flourishing of his descendants.

“In the past, people could grasp the homeowner’s mindset by examining these carvings, as they encapsulated the owner’s aspirations and wishes. Consequently, buildings served not only as residential spaces but also as spiritual sanctuaries for their inhabitants,” she added.