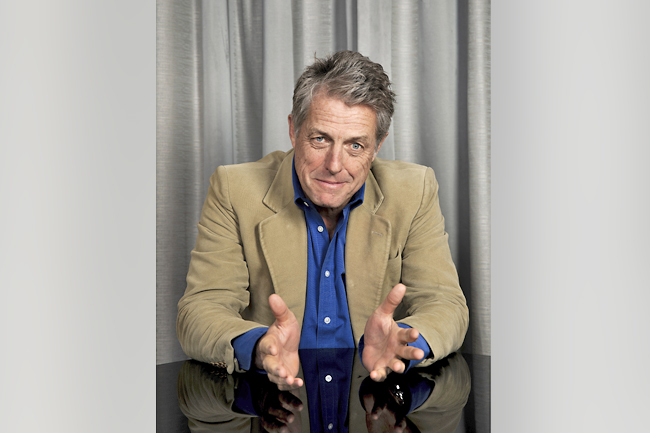

NEW YORK (AP) – After some difficulties connecting to a Zoom, Hugh Grant eventually opts to just phone instead.

“Sorry about that,” he apologised. “Tech hell.” Grant is no lover of technology. Smart phones, for example, he calls the “devil’s tinderbox.”

“I think they’re killing us. I hate them,” he said. “I go on long holidays from them, three or four days at a time. Marvellous.”

Hell, and our proximity to it, is a not unrelated topic to Grant’s new film, Heretic. In it, two young Mormon missionaries (Chloe East, Sophie Thatcher) come knocking on a door they’ll soon regret visiting. They’re welcomed in by Mr Reed (Grant), an initially charming man who tests their faith in theological debate, and then, in much worse things.

After decades in romantic comedies, Grant has spent the last few years playing narcissists, weirdos and murders, often to the greatest acclaim of his career.

But in Heretic, a horror thriller from A24, Grant’s turn to the dark side reaches a new extreme. The actor who once charmingly stammered in Four Weddings and a Funeral and who danced to the Pointer Sisters in Love Actually is now doing heinous things to young people in a basement.

“It was a challenge,” Grant said. “I think human beings need challenges. It makes your drink taste better in the evening if you’ve climbed a mountain. ”

Heretic is directed by Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, co-writers of A Quiet Place. In Grant’s hands, Mr Reed is a divinely good baddie – a scholarly creep whose wry monologues pull from a wide range of references, including, fittingly, Radiohead’s Creep.

In an interview, Grant spoke about these and other facets of his character, his journey from rom-com idol to horror villain and his abiding affection for The Sound of Music.

AP: In this descent in darker territory, nothing may be more daring than your Jar Jar Binks impression in Heretic.

GRANT: Yes, thank you. It’s not easy for any actor.

Was that scripted or did it come from you?

It’s hard to remember which was the writers, which was me. But I’m pretty sure doing the Jar Jar Binks impersonation was my idea.

So you knew you had a Jar Jar Binks impression in you?

No, I didn’t. I just thought it would be fun if the character did that because it’d be just weird.

And, in fact, what’s odd about me is that I’ve never seen a Star Wars film.

Have you seen many horror films?

I can’t. They’re too frightening for me. I watched The Exorcist when I was too young and I’ve been in counselling ever since. I watched one by mistake recently, which was Midsommar.

I thought it looked like a jolly, Swedish comedy. I put it on one evening for my Swedish wife who needed cheering up and she’s still very, very traumatised.

Do you have any theories on why horror has been so popular in recent years?

It’s fascinating, isn’t it? I don’t know. Maybe these are the end of times, the end days, the apocalypse. We know it deep down but for some reason we won’t confront it. I don’t know, but it’s wonderful that it sends people into the cinemas.

You’ve spoken before about your affinity for the big screen. Is the seeming decline of theatrical moviegoing a concern for you?

It is. Talk about the end of days. To me, one of the gloomiest signs or omens is the gradual closing of cinemas – and not just that, where I live in London, but the closing of restaurants. The restaurant where I met my wife, which was party night every night of the week, is now largely closed. I think the fact that we’re all staying in, staring at our devil’s tinderboxes is deeply tragic, or watching things on streaming by ourselves with maybe one or two other family members. These things should be collective experiences.

One element that you’ve said factors into your choice of roles is whether you believe the film will be entertaining. Do you find your gauge for that is still accurate?

My ability to gauge what’s entertaining, I used to be very proud of it. In the old days, my old career, I used to say, “I’m not so proud of my acting but I’m proud of the fact that the films I’ve done, on the whole, have been entertaining and I’ve been good at choosing them.”

And then, suddenly overnight, I became very bad at choosing them. I don’t know, I lost the zeitgeist, I suppose. That can happen. Now, I feel like I’ve found something again. If the character amuses me and I think I’m going to enjoy being that person, then I tend to do the job. Sometimes, when actors are enjoying it, it works.

So you go more now on what you personally respond to?

Yes, I’ve got nothing else to go on. And I’m not the lead character, the film doesn’t rest on me. I don’t have to worry that much if it does well, medium or badly. I just go by: Do I think I’m going to have some fun in this?

When would you mark this shift for you?

The big shift was after Did You Hear About the Morgans? That was sort of officially the end of romantic comedy for me. Nothing much happened after that in showbiz terms.

I went off and did political campaigning and I was quite happy, in fact. But in drips and drabs, strange little projects, like the Wachowskis’ Cloud Atlas, then Stephen Fears came along with Florence Foster Jenkins and A Very English Scandal. Paddington 2. These interesting, complex, often not very nice, narcissistic weirdos started to emerge from the woods.

I always thought, while you made some excellent comedies, you had the misfortune of becoming a star when Hollywood wasn’t so great at making comedies.

Looking back, I was very lucky. I had Richard Curtis on the one hand, who is not only a gifted comic writer – he can just do flat-out comedy like Black Adder – but he’s an unrecognised dramatist.

Those comedies are based on pain. The comedy is there to deal with pain. It’s people with unrequited love, lost love, bereavement, brothers with mental illness – proper pain. So I was lucky with him.

And I think I was very lucky with Marc Lawrence who just had a wonderful gift for the celebration of life. He actually likes people, which is so weird. So films like Music and Lyrics have a very sustaining and uplifting buoyancy to them. He’s an unrecognised talent.

I do like his movies.

You know who really loves them? The most surprising person in the world. Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino pushed his way through a crowd at a party in London once to say, (does Tarantino impression) “Man, I loved Music and Lyrics and Two Weeks Notice.”

He told me the whole plot of both films and how he was watching one of them on a plane and the plane landed and he had to rush off to a DVD shop to buy the disc so he could watch the end of it. I thought maybe he was joking but I don’t think he was. Someone told me at his cinema here in Hollywood, a rather cool, 35mm-showing theatre, he’s been showing Music and Lyrics, no less.

Perhaps that’s a bit like how you feel about ‘The Sound of Music’.

Yes, my enthusiasm for that film has spread. I’ve just been invited to a 60th anniversary next year in Salzburg. I might go. I might wear lederhosen. Or I might wear a white dress with a blue satin sash, as I did in school when I played Brigitta Von Trapp.

Is that true?

Yeah, I was at all-boys English school and I played, I think, the third youngest daughter.

Is anything else on the level of The Sound of Music to you?

The older I get the more I love song and dance. I find myself watching a lot more Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, things like that. ecause life is so stressful and the news is so ghastly that it’s hard to watch very serious stuff and pick yourself up afterwards. I did watch The Zone of Interest coming over from London the other day. And I have to say that’s just about as good as filmmaking gets. – Jake Coyle