Ron Charles

THE WASHINGTON POST – Our love for murdered women doesn’t do them much good.

Stories of their deaths lure us to popular podcasts, TV investigations and magazine exposés. Their bodies – or parts of them – electrify best-selling thrillers and blockbuster movies. As a culture, we seem equally alarmed and aroused by these tales of slaughter.

In her devastating study of domestic violence, No Visible Bruises, Rachel Louise Snyder notes that 50,000 women around the world were murdered by their partners or family members in 2017. That’s about six lives snuffed out by a “loved one” every hour of every day.

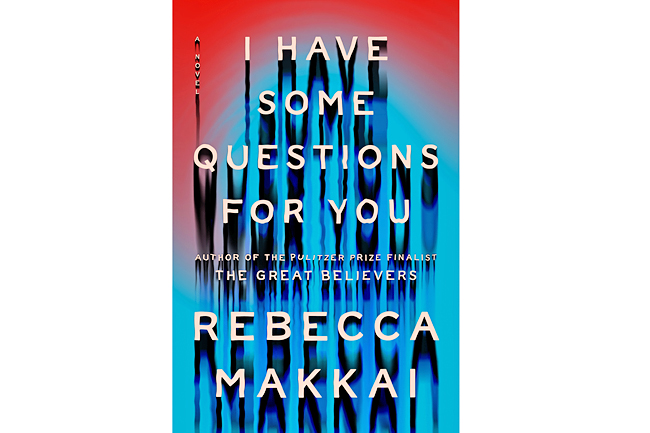

One minor but grotesque marker of this epidemic is the way we struggle to keep the most shocking cases straight amid so many. Rebecca Makkai highlighted that predicament throughout her troubling new novel, I Have Some Questions for You. It begins with people trying to remember which murdered woman they’re talking about: “Wasn’t it the one where she was stabbed in – no. The one where she got in a cab with – different girl. The one where she went to the frat party, the one where he used a stick, the one where he used a hammer, the one where she picked him up from rehab and he – no. The one where he’d been watching her jog every day? The one where she made the mistake of telling him her period was late? The one with the uncle? Wait, the other one with the uncle?”

That Whitmanesque catalogue of carnage eventually arrives at the sad case of a 17-year-old girl named Thalia Keith. In 1995, just after a performance of Camelot at the prestigious Granby School in New Hampshire, Thalia was murdered. An athletic trainer – a rare Black man on campus – confessed to the crime, but conspiracy theorists have punched holes in the investigation for decades. Dateline re-examined the case in 2005, and journalists have bestrewed the story with maudlin Camelot metaphors for years. “Boarding school as kingdom in the woods, Thalia as enchantress, Thalia as princess, Thalia as martyr. What could be more romantic?” the narrator asked bitterly. “What’s as perfect as a girl stopped dead, midformation?”

This deeply conflicted narrator is Thalia’s former roommate, Bodie Kane. Back in the 1990s, when her own family disintegrated, Bodie was sent away to Granby and dunked in its rarefied aura. Now, almost 25 years later, she’s a professor of film and the host of a popular podcast about the way Hollywood chewed up female stars in the Golden Age. She’s been asked to return to Granby and teach a pair of seminars during a special winter session.

The invitation draws Bodie back with a mixture of nostalgia and dread. The stately school looks preserved in amber, but visiting awakens forgotten and disorienting memories. Bodie recalled the horror of Thalia’s murder, her own tangential role in the original investigation and especially Mr Bloch, a music teacher whose behaviour seems, in retrospect, suspiciously creepy.

And so, it’s to him – charismatic, overly familiar Mr Bloch – that Bodie addresses this entire narration. He is the “you” in the title, and he floats across all these pages, often unseen and forgotten until Bodie snaps him to the centre of our attention again, as when she ends a chapter by saying, “I didn’t understand yet that I was there on your trail, that I wanted answers from you. But the subconscious has a funny way of working things out.”

In one sense, that’s what this novel is: an attempt – both reluctant and obsessive – to work out exactly what happened 23 years ago and why that crime was so neatly packed away.

Makkai, whose 2018 novel, The Great Believers, was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, controls conflicting currents of intrigue under the placid surface of this story. There would seem to be little drama in teaching a couple of classes to smart, articulate teens on a lovely, snow-covered campus. But Bodie is secretly thrilled when one of her podcast students decides to investigate Thalia’s murder, a la Serial.

While trying to maintain some semblance of teacherly objectivity, Bodie is excitedly drawn back to the years she spent as a moody teenager and a keen observer of Thalia. As she strains to remember the events before and after the murder, she recalls the culture in which high school boys were trained to be stars and girls were expected to be their adoring fans.

But it was more than just that; it was a place of jocular harassment where young men mocked girls, groped them and always insisted that their victims regard this humiliation as affection or mere hilarity.

If they noticed that behaviour, the teachers and administrators did nothing to stop it. Boys, after all, will be boys.

Prep-school novels – a surprisingly large genre given the smallness of private-school attendance – are usually cloistered in sweaty isolation. But this is a story that constantly casts our attention to the outer world. The shameful behaviour in the school’s past resonates clearly with the #MeToo accusations that Bodie keeps reading about on social media, along with stories of President Trump lashing out at his female accusers.

But Makkai is pursuing something more complicated than a general survey of men behaving badly. Bodie wonders about her own culpability. She questions the validity of the Court of Twitter, where every accusation is its own incontestable proof and every example of boorish behaviour is the moral equivalent of rape. In such a feverish atmosphere, compounded by the ubiquity of actual violence, Bodie finds herself struggling to remember what really happened and what it meant.

Through this complicated story of historical reclamation and present-day reckoning, Makkai explores the way the mistreatment of women and girls is repressed, mythologised and transmuted into lurid gossip and entertainment.

Considering the Hollywood starlets she writes about and the fresh investigation of Thalia’s death that she’s encouraging her students to pursue, Bodie admited, “I’m queasy… about the way they’ve become public property, subject to the collective imagination.” It’s a tension that this novel, which also participates in that fixation, is fully aware of.

All of this makes I Have Some Questions for You a kind of meta murder mystery that deconstructs its own tropes. Bodie’s voice, so nakedly candid and bravely confessional, is absolutely convincing. I felt as captivated as though someone were whispering this whole novel just to me. By the end, it’s not the brutality of Thalia’s case that’s so terrifying, it’s the commonness of it.

“It was the one where her body was never found. It was the one where her body was found in the snow. It was the one where he left her body for dead under the tarp. It was the one where she walked around in her skin and her bones for the rest of her life but her body was never recovered.

“You know the one.”