JAKARTA (AFP) – Indonesian fruit seller Budi was seeking better prospects when he signed up for an IT job in Cambodia. But he found himself detained in a heavily guarded compound where he was forced to carry out online scams.

“When I arrived there, I was told to read a script,” Budi, not his real name, told AFP on condition of anonymity. “It turned out that we were asked to work as scammers.”

The 26-year-old was put to work 14 hours a day in a site ringed by barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards, he said. His days were punctuated by threats from his supervisors, and the nights were short. At the end of six weeks, he received just USD390 of the USD800 he was promised.

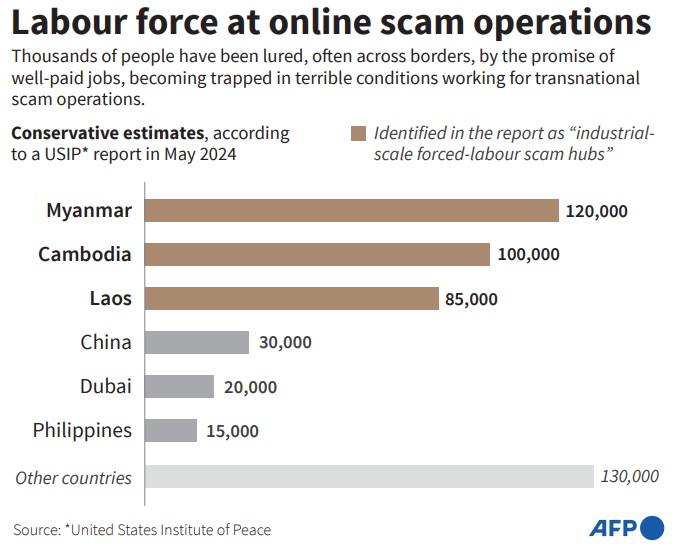

Thousands of Indonesians have been enticed abroad in recent years to other Southeast Asian countries for better-paying jobs, only to end up in the hands of transnational scam operators.

Many have been rescued and repatriated, but dozens still languish in scam compounds, forced to trawl social media sites and apps for victims.

Food stall worker Nanda, not her real name, said her husband flew to Thailand in mid-2022 after his employer went under, jumping at the chance to earn IDR20 million (USD1,265) a month in an IT job recommended by a friend.

But after arriving in Bangkok, a Malaysian agent whisked him across the border with five others to the Myanmar town of Hpa Lu, where he was forced to work at an online scam compound.

The man was made to work shifts of more than 15 hours, facing punishments and verbal abuse for falling asleep on the job.

“He told me what he had experienced — he was electrocuted, and also beaten — but he didn’t tell me in detail to stop me from thinking about it too much,” said the 46-year-old.

She said her husband was sold and moved to another scamming operation earlier this year.

Like Budi, her husband was able to get word out about the conditions he was subjected to during the brief moments he was allowed to use his phone.

Phones are collected at the start of the work day, and call logs and messages screened by the scam operators.

But the furtive communications, sometimes in brief coded words, are often the only clues helping activist groups and authorities to locate the scam compounds for rescue operations.

The government has identified at least 90 Indonesians still trapped in scam rings around Myanmar’s Myawaddy area, said foreign ministry citizen protection director Judha Nugraha (AFP pic left), adding the figure could be higher.

United Nations officials have said those trapped by scam syndicates are experiencing a “living hell”.

Victims have little option but to survive under duress, said Hanindha Kristy of NGO Beranda Migran, which regularly receives pleas for help from Indonesians tricked into scam rings.

“There is a modern slavery practice here, where they were recruited, tricked to work as scammers,” she said.

Budi was able to escape after he was transferred to another scam ring in the Cambodian border town of Poipet.

While grateful for his escape, Budi, who is now working at a palm oil plantation, remains wracked by guilt over the fraud he had been forced to carry out.

“The guilt will be a lifelong feeling, because when we take away people’s rightful belongings, it’s like there’s something stuck in my heart,” he said.