BOLIVIA (AFP) – As a kid growing up in poverty in rural Bolivia, Roly Mamani built his own toys. Now a 34-year-old engineer, he 3D prints limbs for Indigenous compatriots scarred by life-changing accidents.

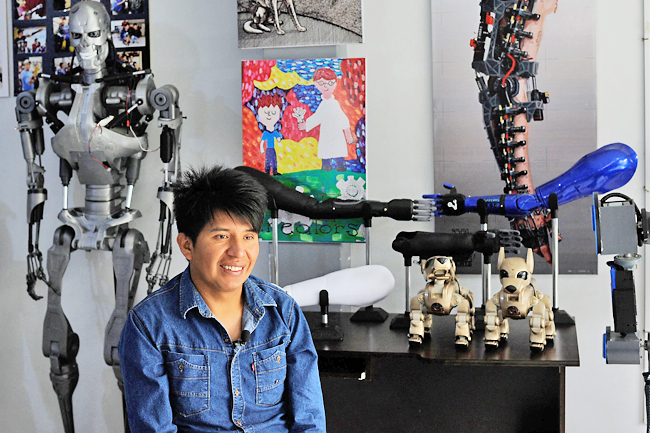

Mamani funds the endeavour with the money he makes from selling robotic toys he makes – his other passion, which, after building his first remote-controlled toy car as a child, he never abandoned.

Surrounded by prostheses, plants and 3D-printed dinosaurs in his study, Mamani pores over an arm he is devising for a boy who lost his due to an electric surge.

It is his purpose, the engineer told AFP, “to improve people’s quality of life”.

The son of small-scale farmers, Mamani grew up in Achocalla, a community nestled between two lagoons some 15 kilometres north of the capital La Paz, verdant with pasture, vegetables and tubers.

With no money for toys, he started building his own play cars from plastic and cardboard at a young age, upgrading in primary school to a motorised version.

Before entering public university, Mamani worked for two years at an automobile workshop where he was exposed to “the first real machines I ever saw”.

Ten years ago, he opened his own workshop in Achocalla to build robotic toys and educational aids.

“You could say I have all the toys I want now,” he said.

Then everything changed when he heard about a rural man without hands and thought to himself: “I can make them for him.”

In 2018, the toymaker of Achocalla set out to find life-improving solutions for other disfigured Bolivians with his 3D printers.

“Science is like a superpower. Robotics is a trend, but if it does not address important things, it doesn’t mean anything,” he mused.

Against the background noise of printers at work, Mamani told AFP he can create six units a month.

Since 2018, “we have made more than 400 prostheses”, he said.

Half were delivered free of charge or at the cost of production, funded by his robotics sales.

On average, a 3D-printed prosthesis in Bolivia costs about USD1,500, more than five times the minimum salary.

A functional prosthesis – the type that allows certain movements – can cost as much as USD30,000.

Yet the public health system does not cover prosthetics, in a country where some 36,100 people have physical and mobility problems, according to the state-aligned National Committee of People with Disabilities.

Mamani himself chooses the recipients of his donations from the countless requests he receives, including from abroad.

“The people in the most need are those who work precarious jobs without safety, which is why they have these accidents in which they lose a limb,” he said. One of their beneficiaries is 59-year-old Pablo Matha, who lost his vision and right hand seven years ago in a mining accident involving dynamite.

After that, “I went out every day to ask for some coins (on the street.) That’s where my friend Roly and his brother found me”, Matha told AFP.

Mamani’s brother Juan Carlos is a physiotherapist, who helps with the patients’ physical rehabilitation.

Matha said the prosthesis helped him regain his self-respect. He now plays the guitar to earn a living.

He said he used to “feel people looking at me and laughing. But now that I have the prosthesis… sometimes I feel that I am like any ordinary person”.

Marco Antonio Nina, 26, was another recipient. As a teenager, working on a masonry project, an electric shock severed his left arm and stunted the right one.

“I like to sing, but without the prosthesis it hurt to hold the microphone… Now with this, it’s a blessing,” he said.

Mamani wants to use the recognition he has won for his work – he has been awarded a US robotics scholarship – to set up a rehabilitation centre.

“I want to generate my own technology, I have to improve,” he said.