Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – I didn’t grow up in the Marvel Universe. Between the ages of eight and 13, I was raptly devoted to DC Comics, to the adventures of Superman, Flash, Green Lantern and the whole crew of the Justice League of America. In fact, one of the half-dozen greatest days of my life occurred when a friend simply gave me two dozen DC comics he no longer wanted. After riding my bike home from his house, I spread out this miraculous bounty under a living room lamp, and then spent a long evening with a plate of freshly baked cookies while reading, reading, reading, my heart almost bursting with delight.

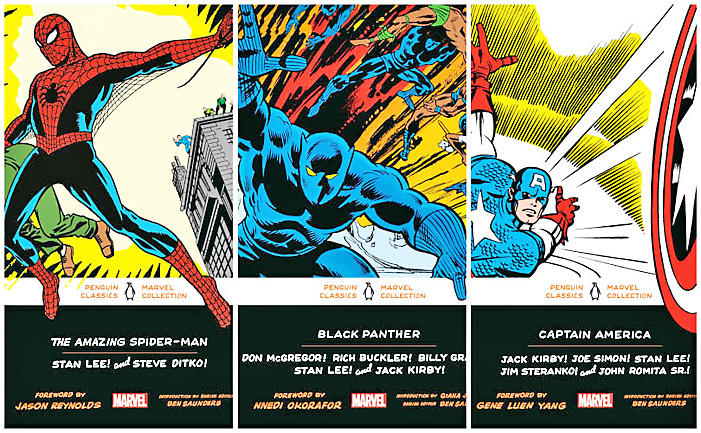

All this past spring, then, I was eagerly looking forward to recapturing some of that ancient enchantment by immersing myself in six colourful volumes of Marvel superhero comics: three Penguin Classics collections of the early adventures of Spider-Man, Captain America and Black Panther, and three Folio Society best-of collections devoted to Spider-Man, Captain America and Hulk.

For fans, both series are desirable and contain little overlap. The general editor of the Penguin editions, Ben Saunders, a comics scholar from the University of Oregon, provides historical background on how Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and others co-created these modern legends. Contemporary writers such as Qiana J Whitted, Gene Luen Yang, Jason Reynolds and Nnedi Okorafor contribute additional introductions or winningly personal forewords.

Appendixes feature recommended reading lists and sometimes supplemental essays, such as Don McGregor’s memoir of how he wrote the multi-issue Panther’s Rage, which supplied some of the plot elements to the Black Panther movie. Each of these collectible Penguin hardbacks runs to roughly 350 pages and is priced at USD50. Paperback editions cost USD28.

The Folio Society volumes cost USD125 apiece, but for purists they offer a slightly more authentic reading experience. While Penguin’s imaging is bright and crisp, its paper stock looks a little too shiny, smooth and white. Folio more faithfully replicates the slightly faded colours and pulpiness of the original comics. Roy Thomas, a former editor in chief at Marvel, not only chose the contents of each omnibus but also outlines the creative decisions behind these high-spot adventures of Hulk, Spider-Man and Captain America. Each volume is housed in a sturdy slipcase and comes with a significant extra – a separate facsimile of the actual issue in which the superhero first appeared.

Now comes the sad part: Being a devotee of older popular fiction, I was surprised – no, dismayed – that these Marvel comics never really cast a spell on me. Perhaps I expected too much from them. While the art and page layouts are dynamic and highly imaginative, the writing ranges from hokey to flatly utilitarian to histrionic. The stories carry few surprises, and the majority contain the same general plot driver: an acute tension between each protagonist’s actual self and his public persona, between the all-too-human beings inside those skintight get-ups and the formidable superhumans they have been called to be.

As a result, nearly all Marvel superheroes – at least as far back as the 1960s Fantastic Four – are troubled and unhappy. They accept that great power confers great responsibility but remain unsure whether they can shoulder the burden. In principle, their self-doubt, sometimes verging on self-pity, invests them with a humanising psychological complexity.

Similarly, we are even made to sympathise with their adversaries, who regularly view themselves as deeply wronged or entitled to revenge. Angst, among both heroes and villains, is the predominant emotion within the Marvel Universe.

Thus, the teenage Spider-Man lacerates himself as a social misfit and suffers guilt over the deaths of several loved ones. Thawed from a cryonic deep-freeze, World War II’s Captain America feels alienated in the modern era and misses his long-dead junior partner, Bucky Barnes. Black Panther endures both physical ordeals and grave questions about his worthiness to carry on the kingdom of Wakanda’s traditions. And the invincible Hulk is dumbly aware that inside his green skin lingers an unwillingly transformed Bruce Banner. Banner’s own Hulk-inducing rages are eventually, almost inevitably, shown to be a consequence of abuse as a child.

Compared with the DC comics I enjoyed in elementary school, Marvel targets a slightly older audience, consisting mainly of adolescents and 20-somethings who can readily identify with sensitive, emotionally roiled characters. No doubt, this shift was partly market-driven – older readers have deeper pockets than allowance-dependent 10-year-olds. But Marvel’s better writers and artists were also hungering to “make it new”, to explore and extend the aesthetic possibilities and cultural impact of their medium – something which contrarian underground “comix” had already been doing.

After all, before this still-ongoing sea change, superhero comics generally proffered a suburban, picket-fence vision of American life and hurtfully ignored social, sexual and racial realities. In that sense, today’s Marvel Universe represents a highly welcome advance.

Nonetheless, by growing increasingly relevant and naturalistic, superhero comics – not just from Marvel – gradually lost much of their joy along with their naivete.

That process, though, has barely begun in these albums, which emphasise work published in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. Here, the story arcs still tend to be as action-oriented as one could want, pitting costumed good guys against highly melodramatic bad guys, mad scientists and improbable monsters. By contrast, contemporary superhero comics – from a variety of publishers – are quite another matter: My childhood’s brightly coloured land of dreams has morphed into a universe of nightmares and case histories. Enter any specialty comics shop – the days of drugstore spinner racks are, sadly, long gone – and the darkness will surround you. Much of the artwork you’ll see is shadowy, stylized and brutalist, while numerous covers spotlight busty super-babes in gleaming leather.

But, as I say, that’s now. For the most part, these Penguin and Folio Society retrospectives only hint at the bleakness to come. Claims for artistic greatness, however, strike me as exaggerated. You may feel differently.

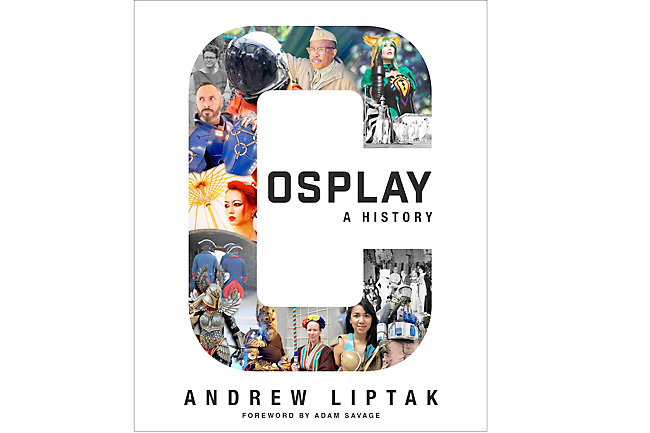

At least, I continue to be childishly delighted by adult cosplay, the practice of dressing up as a favourite fictional or cinematic character. As our troubled superheroes know, donning a mask can be liberating, a way of releasing one’s deeper self. Appropriately, Andrew Liptak’s opens his chatty Cosplay: A History by looking at costume balls, historical reenactors, Halloween and the tradition of masquerade night at science-fiction conventions. Still, his heart really belongs to the Star Wars franchise.

As a result, the book swarms with white-armoured stormtroopers and ragtag rebel legions.

There are scattered photos of comics, manga and anime-inspired outfits, as well, but where are the steampunks in their elaborate Victorian splendour? Or the sword-wielding Conan wannabes?

These cavils aside, Liptak’s history is generously packed, almost overpacked, with information about cosplay fandom, including chapters on legal issues and costume manufacture. Appropriately enough, San Diego Comic-Con – the Carnegie Hall of cosplay – will soon be in full swing this year, from July 21 to 24.