Hyungwon Kang

ANN/THE KOREA HERALD – Korean burial tradition includes burying treasured items of significance with the deceased. Most valued objects in the Korean antiques trade are treasures which were originally buried in ancient tombs.

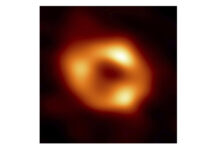

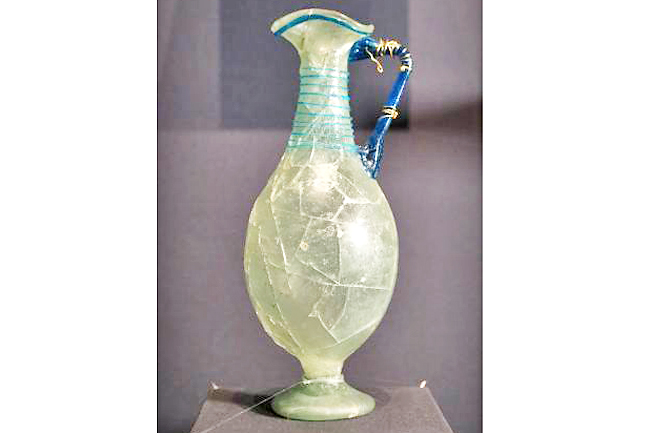

A 5th-century Silla-period phoenix-shaped glass pitcher, dug up in 1975 from Hwangnamdaechong, the largest royal tomb of Silla, has intrigued Koreans for decades about its origin as its aesthetics looked of a foreign nature.

It was not until researchers made the connection between some 30 glass products excavated from Silla royal tombs in the ancient Silla capital, Gyeongju, to similar glassware found in central Asia and the Middle East, that they confirmed the ancient trading of Roman goods through the Steppe Route, the original Silk Road over the Eurasian plains stretching all the way to Far East Asia.

A professor and director of the Silk Road Survey and Research Centre in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Kyungpook National University in Daegu Park Cheun-soo has dedicated more than a decade chasing the origin and the route through which Roman glass products ended up in Silla, some 12,000km away.

Park found a glass cup excavated from a tomb in Kara-Agachi, Kazakhstan, whose fishnet design was strikingly similar to that of a sixth-century Silla-period glass cup excavated in 1926 from Seobongchong, one of the many ancient Silla tombs in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province.

Such rare foreign objects are believed to have changed hands several times before they reached Silla, according to researchers.

“Ancient traders of Gojoseon and subsequent Korean kingdoms such as Buyeo and Goguryeo, brought foreign treasures to Silla,” said Park.

“Historically, ancient nations were formed to protect their economic interests. Competing neighbouring states defined each other as nation states when they traded goods. Nation states had to trade goods for survival,” said a professor of archaeology and director of Gojoseon Research Institute at Inha University in Incheon Bok Gi-dae.

“Korean people are descendants of the survivors of ancient Hongsan culture, which date back to about 4,700 to 3,000BC,” said Bok.

He found evidence of a partial collapse of civilisation in ancient Hongshan culture which was a Neolithic culture in the Liao river basin in the north of the Balhae Sea, not far southeast of present day Beijing.

“Climate change combined with drought and a drop in temperature led to a possible plague some 5,000 years ago. We found mass graves of ancient people’s remains with no war wounds,” said Bok, adding that he discovered that the genetic markers of modern Koreans matched those of the remains from the ancient Hongsan culture.

Korean people’s love for all things made of glass is well-documented in the Three Kingdoms Wei Shu and Dongyi Biography (280-289) by the writer Chen Shou who wrote that “Korean love to wear jewellery with glass more than jewellery made with gold or silver.”

Baekje people already had the technology to make glassware in the second century, but imported glass products were considered more valuable for the royalty.

The Roman Glass pitcher, discovered in 1975, must had been a really valuable import for the Silla royalty, as its handle is wrapped with gold wires.

Grave robbers have been one of the oldest traders. Most antique objects in Korea’s museums can trace their origins to ancient graves.

Goguryeo Kingdom, which continued the ancient cultures of Buyeo and Gojoseon, had a tradition of maintaining royal tombs. Goguryeo left detailed instructions for future generations on a massive stone monument to honour their King Gwanggaeto the Great of Goguryeo (374-413), whose legendary expedition stretched Goguryeo’s influence far beyond the Korean Peninsula.

According to the text on the 6.39-metre-tall stone monument, Gwanggaeto the Great’s graves, along with the rest of the royal tombs, were to be managed by 330 gravekeeper households called sumyoin.

Considering there were only 20 households designated to manage Silla ancestral royal tombs in the south, and similarly some 20 gravekeepers for the Northern Yan kingdom (407-436) graves in the west at the time, the sheer number of sumyoin dedicated to the protection of Goguryeo’s royal tombs speaks volumes about the size and the wealth of the Goguryeo empire.

Virtually no Roman glassware have been found in the Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534) during the fifth century nor during the Song dynasty (960-1279) in China.

At the same time, many Roman glass products were traded over the Steppe Route, the original Silk Road over the northern plains that ended in Silla.

Researchers have determined that glass products were produced at four locations during the Roman period: Rome, Alexandria, Syria and the Roman colony of Cologne, Germany.

“The Phoenix-shaped glass pitcher dug up in 1975 was made in Syria,” said Park.