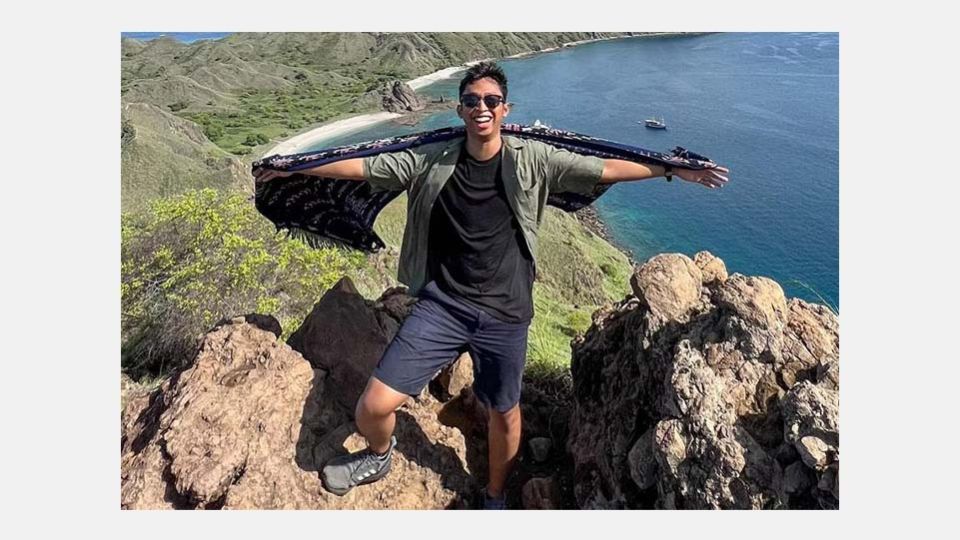

JAKARTA (ANN/THE STRAITS TIMES) – In the bustling streets of Jakarta, amidst the clamour of modern life, Mr Zavaraldo Renaldy, a 28-year-old mapping surveyor, stands as a symbol of Indonesia’s shifting societal norms.

Educated, successful, and single, Mr Renaldy defies his parents’ traditional expectations by prioritising his career over marriage. Despite his openness to casual dating, he remains steadfast in his reluctance to commit to long-term relationships, much to his family’s dismay.

As Indonesia grapples with evolving attitudes towards matrimony, Mr Renaldy’s story reflects the complex interplay between tradition and modernity in the country’s social fabric.

A growing number of people in Indonesia, like Mr Zavaraldo, are putting off marriage. A total of 1.58 million couples said “I do” in 2023 – 128,000 fewer than in 2022. That number has been steadily falling since 2018, when 2.01 million marriages were recorded in the world’s fourth-most populous nation, according to Indonesia’s statistics agency.

“With very high competition in the workforce and expensive housing prices, you need more time to get ready to settle down and start a family,” said Mr Zavaraldo, who plans to marry only in his mid-30s.

Although Mr Zavaraldo’s parents are keen to see him settle down and start a family, he is adamant that nuptials will have to wait. Later in 2024, he plans to pursue his master’s degree in the Netherlands, in what he hopes will be a career-enhancing move.

While declining marriage figures might be common in countries with shrinking populations, Indonesia’s population is actually growing each year, which underscores concerns by experts of changing attitudes towards marriage.

South-east Asia’s most populous nation recorded a population of 277.5 million in 2023, compared with 267 million in 2018.

“Indonesia’s young population has been on the increase, but the number of marriages nationwide has been declining,” said sociologist Dede Oetomo, a professor of gender studies at Airlangga University in Surabaya, East Java.

Declining marriage rates would jeopardise Indonesia’s stated target of becoming a developed country by the time it celebrates its centennial of independence in 2045.

Indonesia wants to capitalise on its current demographic bonus – a period in which people of working age outnumber those who are economically dependent, which will peak between 2020 and 2035 – to avoid being stuck in the middle-income trap, Indonesia’s family planning agency (BKKBN) head Hasto Wardoyo told the source.

“If we do not do it right, the demographic bonus will pass, and it never gives leverage for the people’s welfare. Our population must be adequately high if we want to avoid a middle-income trap,” said Mr Hasto.

Countries fall into the middle-income trap if they are not able to move from a low-cost to a high-value economy. In order to transition successfully, there must be high enough population growth to help fuel economic growth. Hence, there is concern over declining marriages and subsequent birth rates.

At the same time, divorces are more common now, with 500,000 a year, compared with 10 years ago when there were between 250,000 and 300,000, noted Mr Hasto.

Indonesians as a whole are becoming more individualistic, choosing to pursue personal goals instead of following traditional and cultural norms that emphasise the wider society, and having a harder time committing to marriage and all it entails, said Mr Hasto.

A better-educated workforce and the financial burdens of marriage and children are perhaps the biggest factors standing in the way of Indonesian couples tying the knot, sociologists told the source.

While the Indonesian economy has shown resilience in its recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic – which lasted from 2020 to early 2023 – the fallout is still felt on the ground, said Jakarta-based sociologist Musni Umar, adding that during that period, many lost their jobs and fresh graduates in particular faced a much harder time entering the workforce.

Since then, Indonesia has seen foreign investment inflows into the country and has booked decent export numbers, but these developments have not been best translated into jobs locally, Dr Musni noted.

Indonesia’s overall unemployment rate is one of the highest among its neighbours, standing at 5.3 per cent in August 2023. But its youth unemployment rate, referring to those ranging in age from 15 to 24, was much higher, at 19.4 per cent, according to Indonesia’s statistics agency. In comparison, Malaysia’s overall unemployment rate in January 2024 was at 3.3 per cent, according to Malaysian government data.

“A lot of things boil down to the economic factor. If the breadwinner husband loses his job, and hence income, his wife would most likely leave him. And those who haven’t found a job do not dare to get married,” Dr Musni told the source.

Some observers point to Indonesian Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati’s too early move in ceasing the government’s Covid-19 incentives – affecting the country’s post-pandemic recovery – and while the government has offered free technical training and seminars to those who were laid off during the pandemic, any meaningful impact on growing the job market remains to be seen.

“If you get married, you have to move out of your parents’ house and have a new home,” said Mr Zavaraldo, adding that this is an extra expense he is not quite ready to handle.

The once-popular belief to “just get married first and whatever happens next, we face it together” has significantly faded, said Airlangga University’s Dr Dede, pointing out that decades ago, it was common for multi-generational families to live together. However, with the rise of nuclear families, young couples now bear the burden of finding affordable housing on their own.

And this is even before children enter the picture. The decline in marriage rates is mirrored by the decline in Indonesia’s total fertility rate (TFR), or births per woman. It recorded a TFR of 2.18 in 2022, compared with 2.48 in 2010, according to its statistics agency.

“It’s not that they hate children,” said Dr Dede, adding that the younger generation is very practical and hesitant about starting a family without first ensuring they are financially ready for such long-term commitments.

Even so, not everyone who is able to afford to start a family is thinking about marriage as the next step, said Dr Dede, noting the influence of modern views and with that, an increasing acceptance of individuals who choose to remain single or simply live together.

As a growing number of women enter the workforce, their increasing economic independence has also had an adverse impact on marriage rates.

“More females are now in the Indonesian workforce and a lot of them delayed marriage, thinking they had worked so hard in schools and had built a good career, so why lose what you have achieved,” said Dr Dede.

Further down the line, concerns over climate change and environmental uncertainty are also among the reasons for staving off marriage and parenthood. But that is another story, for another day.