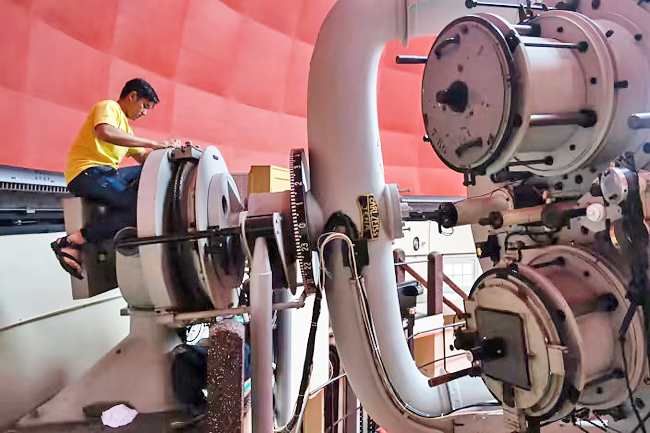

CNA – Since it was opened in 1923, the Bosscha Observatory has been drawing astronomers from around the globe, looking to unravel the mysteries of the universe.

But Indonesia’s oldest astronomical observatory may be on its last legs.

The stars and other celestial objects over the century-old structure are getting dimmer, struggling to compete with the lights emitted from surrounding hotels, restaurants and theme parks as the once tranquil hills of Lembang are turned into a burgeoning resort area.

“Back when the observatory was built, Lembang was sparsely populated. Lembang was occupied by plantations and farmlands. Population was very low. But now Lembang is crowded. It has become a tourism hot spot and as a result, there are many lights,” Bosscha Observatory Director Premana Premadi told CNA.

The light pollution is making it harder for astronomers to conduct their scientific research, said Premadi. Observation of the night sky, she said, can only begin after 11pm, granted that the sky is clear. Even then, scientists can only observe stars at an angle of more than 30 degrees above the horizon. If the telescopes are aimed any lower, the celestial objects would be completely awash with the ambient light coming from the nearby city of Bandung and the surrounding resort areas.

The situation seems to be getting worse. In his 2018 paper, Hendra Agus Prastyo, then a postgraduate student at the Bandung Institute of Technology wrote that within a 20-kiIometre (km) radius from Bosscha Observatory, 195 square kilometre (sq km) or 15.5 per cent of the total area are considered places with high light pollution as of 2017.

Prastyo also wrote that based on satellite images taken between 2013 and 2017, the highly polluted areas are increasing at a rate of 13.7 sq km per year.

A high light pollution area is one where the sky is brilliantly lit and the stars are either dim or completely invisible.

This steady increase in light pollution is alarming for Bosscha Director, Premadi. “There are observatories in Tokyo, in Paris which are now museums, no longer serving their functions,” she said, adding that the scientific community in Indonesia is doing all it can to stop Bosscha from suffering the same fate.

SIGNIFICANT CONTRIBUTION TO ASTRONOMY

When Bosscha was built in the 1920s, the site was an ideal location for an observatory. It sits on the top of a hill at an elevation of 1,300 metre above sea level with a virtually unobstructed, 360 degree view of its surroundings.

Bosscha also has a unique advantage over other, more advanced observatories: its proximity to the equator, allowing scientists to observe both the northern and southern hemispheres simultaneously.

The century-old facility sits at a latitude of 6.8 degree south, which is closer to the equator than Hawaii’s Mauna Kea observatories (19.8 degree north) or Chile’s Las Campanas observatory (29 degree south), both of which boast some of the biggest telescopes and most advanced equipment in the world.

Lembang’s proximity to the equator was one of the reasons why a Dutch industrialist with tea plantations in nearby hills Karel Albert Rudolf Bosscha, chose the site for his philanthropic project: an astronomical observatory.

“In the early 1900s, there was a wave of scientific breakthroughs in Europe like Einstein with his theory of relativity,” Premadi recounted. “All of them needed proof. And you cannot find proof to these theories here on earth. It involves vast amounts of energy, incredible mass and long periods of time. The proof is out there in our universe. People were racing to observe the universe, the stars and the galaxies.”

When the observatory opened its doors in January 1923, European scientists flocked to the facility, studying and recording astronomical phenomenons best viewed in the Dutch East Indies, as Indonesia was known at the time.

Permadi, who has an asteroid named after her, said 100 years since its opening, Bosscha continues to make significant contributions in the world of astronomy and physics, despite not having the most advanced instruments.

Bosscha played a role in the quest to find habitable planets outside of our own solar system, known as exoplanets and it has also contributed to our understanding of how stars evolve.

“Big telescopes in Hawaii or Chile are very competitive. People compete to use these telescopes. So they can only do their research for a short amount of time,” she said. “For more detailed research involving numerous observations over the span of years, you need smaller observatories like Bosscha. Here, they have more time. They can spend many nights here whereas they can only get a few hours with the big telescopes.”

COMPROMISES NEEDED

Located just 8km north of the heart of Indonesia’s fourth largest city, Bandung, light pollution has always been a challenge for scientists at Bosscha throughout its 100-year history.

But the problems multiplied when hotels, restaurants and theme parks began cropping up in Lembang in the 1980s. According to the West Bandung regency government, where Lembang is located, there are now around 200 tourism hot spots in the area, with one or two new attractions being built every year.

The Bosscha Observatory, with its well-preserved colonial style architecture is also listed as one of Lembang’s top tourism hot spots.

Observatory Director, Premadi said the government should facilitate talks between the observatory and tourism players in Lembang. “We don’t want to negate urban development. But we can manage these lights, their design, their type, their position, their height. Use motion sensors, put a hood on street lamps, point the lamps downwards, only turn them on when needed,” she said.

“These kinds of discussions are something that we long to have. There are ways we can both have what we want.”

West Java Governor Ridwan Kamil said his office is formulating a spatial planning regulation aimed at protecting Bosscha.

“The key is balance. It is difficult. People have the right to build but please don’t do it excessively,” Ridwan told CNA.

“I have rejected five permits to build apartments because they will impact water availability, spatial planning, including impact to Bosscha… We will protect (Bosscha) through spatial planning.”

FIGHTING TO STAY RELEVANT

With light pollution worsening in Lembang, the government decided to build another observatory 1,800km away in a sparsely populated area in East Nusa Tenggara province.

The Timau National Observatory, which opened in February, would be the first of many observatories managed and operated remotely by scientists at Bosscha.

“If we have small telescopes in multiple places, they can produce the same result as one giant telescope. It is all about collecting light. We can take turns. The stars might have not risen yet (at Bosscha) but at another facility they are already high up in the sky,” Premadi said, adding that her team is currently looking around for potential locations for a third observatory.

Despite the presence of another observatory in a much more ideal environment, Premadi said century-old Bosscha still has a role to play.

“There is still a lot of work we can do at Bosscha,” she said. “Bosscha will not be moved. It has a long history, long experience.”

Premadi vowed to keep educating the public about the need to keep light pollution in check in the hope of keeping Bosscha functioning as a working observatory.

“In Jakarta, people can no longer see the stars. Seeing the stars is becoming more and more of a luxury. Deep down, people realise that gazing at the night sky and seeing the stars are something that is both very exciting and soothing as well,” she said.

“We hope that nostalgia, that feeling, that longing to see the stars will be the answer. People’s relationship with the sky cannot be replaced by anything else.”