Reagan Upshaw

THE WASHINGTON POST – “You sure know a lot of people who have been in jail,” my wife once remarked. She was right. Even back then, a tally of my art world acquaintances who had done time would have required the fingers of more than one hand. Most of them were dealers who had failed to heed the old trade saying, “Any art dealer who confuses his clients’ lifestyle with his own is in for big trouble.”

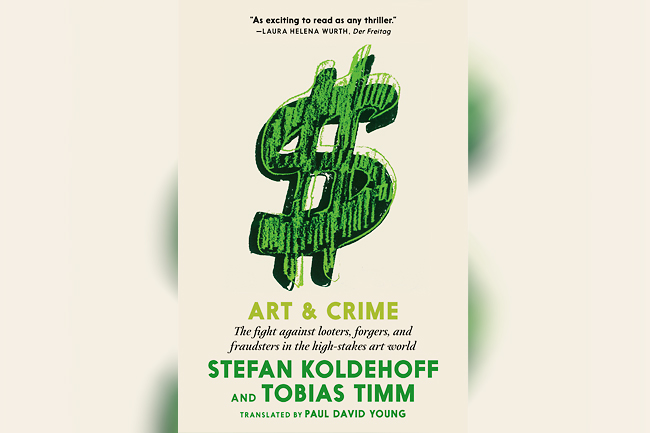

In Art & Crime, German journalists Stefan Koldehoff and Tobias Timm detail the doings of a rogues’ gallery of art scammers, rascals and outright thieves. The action ranges from European watering holes to the New York townhouse of Imelda Marcos to the free port warehouses of Geneva and Singapore, where works of art, legally obtained and otherwise, can be discreetly traded. We see arms dealers buying art to launder dirty money, scholars selling their imprimaturs, auctions being manipulated to boost the market for an artist, and dealers who will purchase a genuine painting at auction and sell a copy of it to an unsuspecting client.

Underneath all of this are forgers whose creations range from phony paintings by Modigliani (a notoriously thorny body of work – for every genuine oil by him, there are four fakes, an expert tells the authors) to watercolours supposedly by the young Adolf Hitler.

There is a chapter on Donald Trump, written especially for the American edition of this book, which details the destruction of some friezes on an Art Deco building in Manhattan that was being demolished to make room for Trump Tower. In the end, however, the book accuses the former president of nothing more serious than bad taste and raging vanity.

Museums, in Koldehoff and Timm’s account (with translation by Paul David Young), are too often complicit with the scoundrels. Curators turn a blind eye to obviously spurious provenances when purchasing antiquities looted from war-torn nations or unauthorised excavations. Directors host exhibitions that are little more than sales opportunities for the people whose “collections” are being displayed.

The authors also scrutinise museums that deal with the thieves who steal their art. Contrary to the cliche of the criminal mastermind orchestrating the theft of a desired masterpiece to grace his lair, most stolen artworks are taken by decidedly plebeian sorts who see a quick opportunity and take it. Unable to sell their loot in the public art market and unable to fence it through their usual contacts, these thieves often put out feelers to the institutions from which it was stolen. Paying ransom for the works might encourage more thefts, but a museum and its insurance company might characterise the payment not as ransom but as “compensation for information leading to the recovery of valuable pictures,” as a museum official described one such transaction.

Ranging as far as it does, from the classical to the contemporary art markets, and jet-setting from one continent to another, “Art & Crime” reads like an assemblage of short exposés cobbled together into a book. Much of the data comes from court records and newspaper accounts, so there is little in the way of surprise. The fact that Donald Trump has atrocious taste has long been evident, as have the tacit negotiations between the compilers of some catalogues raisonnés (scholarly listings of artists’ known works) and dealers with a painting to sell. Art history got into bed with capitalism a long time ago.

Most dealers are honest enough, of course, and there are many scholars and curators who would resign rather than vouch for a work they suspected of being fake. Koldehoff and Timm tell the story of Salvator Mundi, a painting purchased at a small New Orleans auction, authenticated as a work by Leonardo da Vinci, sold to a Swiss art dealer, flipped to a Russian oligarch and finally auctioned at Christie’s New York for USD450 million, reportedly to Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman. It was supposed to be exhibited at a Leonardo exhibition at the Louvre in 2018, but some curators had valid doubts about its authenticity, and the owner refused to lend the work unless it received the museum’s imprimatur. The painting was not shown.

The art business has always had a whiff of the scam about it, for the simple reason that the objects it sells, sometimes for many millions of dollars, have no objective value. Who can “prove” that a painting by da Vinci is worth more than a daub by the most amateur painter? The art market is a maze of shifting fashions, of rising and falling reputations, with nothing guaranteed. What is any painting worth? The answer is simple: It’s worth whatever somebody is willing to pay for it today.

Koldehoff and Timm call for more openness in the art business, lamenting the lack of transparency in terms that might apply to Mafia dons: “There is a weird collective spirit in the art world … an insistence upon outmoded traditions that invite suspicion, from the handshake deal to the anonymity of business partners to the code of silence.” Perhaps art dealers will change their ways, but until that happens, it might be wise to remember the adage about a fool and his money.