Rizal Johan

THE STAR – Malaysian contemporary artist Anurendra Jegadeva, or better known as J Anu, is showing no signs of slowing down after undergoing heart surgery last year in Australia, where he has been based since 2015 (his second stint Down Under, the first being in the early 2000s).

After the successful operation (a quadruple bypass) and recovery process which took a few months, Anu went straight back to work in his home studio in Melbourne and painted right until a new exhibition deadline arrived last month.

The result is a collection of “small works” according to the artist under the title …dan lain-lain – small pictures, large drawings… and others, an exhibition that is currently showing at Wei-Ling Gallery in Brickfields, Kuala Lumpur.

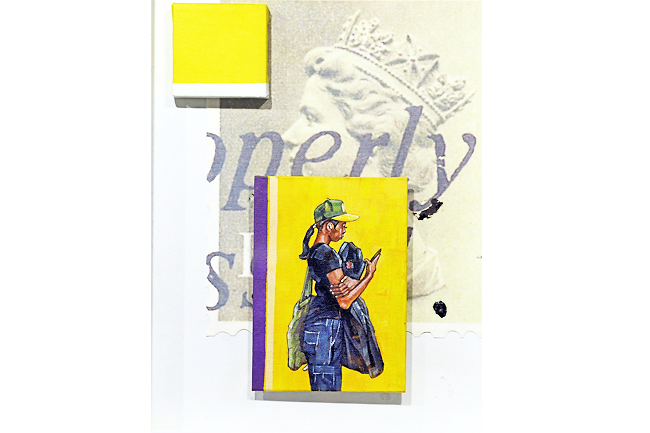

The show, compact in size, offers an array of art pieces using crayons, colour pencils, collage, painted objects, 3-D reliefs, ornaments, miniature toys, stamps and a multitude of personal collectibles for his works.

“I had my surgery September last year. Some of the work started before that like Endless Purnama,” said Anu, who found himself later – post-surgery – working on smaller canvas and board sizes.

In a recent interview at the gallery, the personable artist reflects on how he changed his approach in making the art and what are the new works are about.

“After the surgery everything I did was small brush because I could only work with small works,” added the 58-year-old, who was one of four artists to represent Malaysia at the country’s first ever National Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia in 2019.

The … dan lain-lain exhibition, of assemblages, is a celebration of Anu’s recovery progress.

This new energy can be felt through the group of smaller – impish – works at Wei-Ling Gallery.

“The collection of smaller pictures that fed on each other is my attempt to try and say bigger things. But not too much. For me, mostly, they are like little gems of indulgence and beauty, done purely for their own enjoyment,” he noted.

A SENSE OF PLAYFULNESS

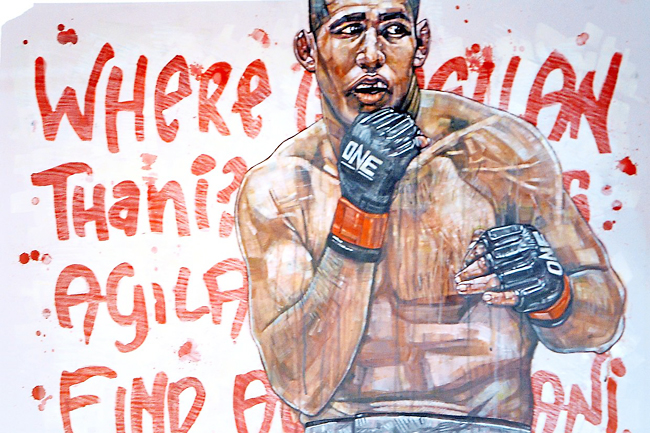

Interestingly enough, the last three works (Finding Agilan Thani I, II and III) for the exhibition were all done with a big brush.

These large works pay tribute to Agilan ‘Alligator’ Thani, a Malaysian mixed-martial arts (MMA) exponent, who started off as a janitor in the gym, before becoming a champion in the ring.

“I stumbled on him one day on Instagram, tried to establish contact but with dismal results.

“I am hoping these works will get his attention. It was his monumentality which inspired the transition to making large works. It made me want to paint. His vitality is contagious even though we have not met. And he demands a big brush,” said Anu in the exhibition notes.

“This is the first time I only worked with one big brush, the whole thing! Everything from the fingers, everything (with one brush). It was really fun. So I’m learning every day,” he recalled.

For an artist as experienced as Anu, who has been consistently painting and generating work for at least two decades, it wouldn’t be out of place to ask what his favourite colour is. “Red!” he reveals after thinking about it.

“Red is easy… it lifts everything. It’s the colour of blood… My palette is very Thaipusam-lah. Bright! Sometimes I try to dull it down, like those are a bit duller (pointing to the Finding Agilan Thani paintings) but they’re still bright. Maybe that’s the Indian fella in me, I don’t know what it is.”

Unlike his previous exhibitions which had an overall theme to it to tie all the art together under one roof so to speak, …dan lain-lain seems random, loose and adventurous like the title suggests.

“They are all small (the art) and small is generally insignificant right? So are they substantial enough to be a show or is it just ‘dan lain-lain’? And I like the ‘dan lain-lain’ because, for the longest time, we have been dan lain-lain, right? Especially if you look at the racial make-up of the country,” said Anu.

“And it’s a very useful phrase because it’s an umbrella phrase for anything. I’ve always loved Bahasa Malaysia, it’s a beautiful language. It’s a simple language but dan lain-lain can mean eight different things or a thousand things because ‘dan lain-lain’ can be anything.

“And it’s a jumble of things as well which is strangely coherent. It’s bizarre. As I made them (the paintings), I knew they would eventually come together.”

Figures and portraits are, by far, the most common thread to be found in his latest body of work.

There are various portraits of his late father (My Father And The Astronaut), wife Inpa (Hers; Cold War), daughter Rupa (Rupa Stays for Lunch; On the Way to School), her friend Leanna (Leanna Goes Out), dancer Mavin Khoo (Endless Purnama) and self portraits too (His; Two Clowns And A Porsche).

And not to forget the nameless others, which include female soldiers (Fair And Lovely Dreaming; Fairest of Them All) and protesters (Another Day On The Strip, Headress 2.0), strangers on the streets of London (Subjex I-VII), Buddhist monks (Exodus; Monk Couture 2.0) and the Malaysian grass-cutters (Keepers Of The Green I-VI).

THE DRAWING PROCESS

One of the most difficult things to draw, according to artists past and present, where figure drawing is concerned is hands.

When Anu was posed this question, he took a few moments to respond, candidly.

“Yeah! Leonardo (Da Vinci), all of them, could never draw hands, even the Sistine Chapel when you look at it… and he went away for 10 years to learn how to draw hands,” he exclaimed.

“So hands are a nightmare. The hands are always problematic. But (British artist Lucien) Freud started saying ‘it didn’t matter. So what if they were ugly? So what if they weren’t right? Did they have the right mood? Are they saying the right thing about the person or the mood he is in in the portrait?’.”

So was drawing hands a hurdle for Anu?

“If you look, I have tried to do hands in all these series. It’s amazing you’re asking me this because, hands are a tough thing and this time I said, ‘Since I’m working small, it’s not going to be such a torture because they’d be quite small and I’ll finish them in a little while but let’s just keep painting hands’, so they (the art) all have hands.

“The Agilan Thani ones were easy because he’s wearing gloves,” he laughs and continues, “You see, it’s interesting, even though they (the hands) are covered up, they are fine bits but the minute they are plastic or leather, I can do it easily but the minute I think of them as hands, I’m drawing them and drawing them (over and over again).”

It’s also not necessary to get the hands anatomically right all the time. “Artists always change things because sometimes optically, it doesn’t look right when you draw it compared to when you look at a photo. And that’s one of the problems working with photos… it’s not real, you’re not getting the mood of the thing.

“So you have to be able to use it as a reference but not a crutch.”

War is the dark cloud that looms over his art but one would have to look closely or you would miss it altogether. It stretches from the past to the present be it World War II or Ukraine and others in between.

There are imperial and rebel forces, persecution and occupation, refugees and migrants, those who fight for their country, and those who fight back.

“The first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Rupa (Anu’s daughter) had come for lunch and, you know it’s funny because I was really stuck! I was like, ‘Err, what shall I paint? I’m really tired’. And I tell ya, there’s nothing like a war to get me going.”

And it doesn’t end there as there are more subtle and hidden things for one to ponder.

“There’s a lot of nostalgia, there’s a lot of little stories in the show. The narratives are always very strong but now more than ever – this show especially – I just gave in to all my interests, anything I like at all.

“And I think the scale allowed me that as well. I wanted to actually go in the opposite direction and just use the fact that I couldn’t quite work with bigger canvases to actually just delve into the tiniest possible things I could,” he concluded.